Suicide risk and immigration background of married couples in Sweden

Is it better to intermarry? Using Swedish registry data, Anna Oksuzyan, Sven Drefahl, Jennifer Caputo, and Siddartha Aradhya investigate whether people married to someone from a different ethnic background (i.e., who are intermarried) have a different risk of suicide than those who are married to someone from their same ethnic background.

Suicide and marriage

Suicide ranks high among the causes of death worldwide, accounting for more than one in every 100 deaths globally in 2019 (WHO 2021). A famous study on the social predictors of suicide by the sociologist Emile Durkheim first documented that suicide was less common among married people in 1897 (Durkheim 1897), and more recent research has consistently found the same pattern. Studies broadly show that marriage benefits both physical and mental health through many mechanisms, including the companionship and economic resources it provides. However, they also find that the health benefits of marriage can vary across characteristics such as race/ethnicity (Martínez et al. 2016) and gender (Gove 1973). Less research has examined whether the health benefits of marriage are linked to the immigration background of a person’s spouse. The literature supports conflicting expectations.

Intermarriage and well-being

Intermarriage is widely considered to be one of the strongest indicators of an immigrant’s integration into a host country. Living with a native-born spouse may improve immigrants’ social integration and well-being by helping them learn the language, enhancing their understanding of the host country’s culture and social systems, and facilitating access to social networks and employment. Accordingly, intermarriage has been associated with better economic outcomes among immigrants in Sweden (Dribe and Lundh 2008). Intermarriage may also benefit native-born partners by increasing their cultural capital (Rodríguez-García 2015), which provides advantages in social life.

On the other hand, studies suggest that intermarriage predicts a greater likelihood of marital conflict. Intermarried couples may have sociocultural differences in values, norms, and communication styles. They may also be exposed to discrimination. These circumstances can reduce marital quality and may take a toll on intermarried persons’ well-being. Indeed, prior research shows that intermarriages are less stable than unions between people from the same ethnic background (Kalmijn, de Graaf, and Janssen 2005). A recent study showed that both partners in marriages between native German women and immigrant men had worse mental health than the partners in marriages involving two native-born Germans (Eibich and Liu 2021). These findings collectively imply that the relationship between marriage and mental health may differ by nativity.

Intermarriage and suicide risk

In a recent study (Oksuzyan et al. 2023), we investigated whether suicide risk in Sweden differs between intermarried people and those married to someone from their same ethnic background. The study used national Swedish registry data from the years 1991 to 2016. We included all married individuals aged 18 and older in our analysis (N = 6,249,727). A total of 18,116 deaths due to suicide occurred over the course of the study.

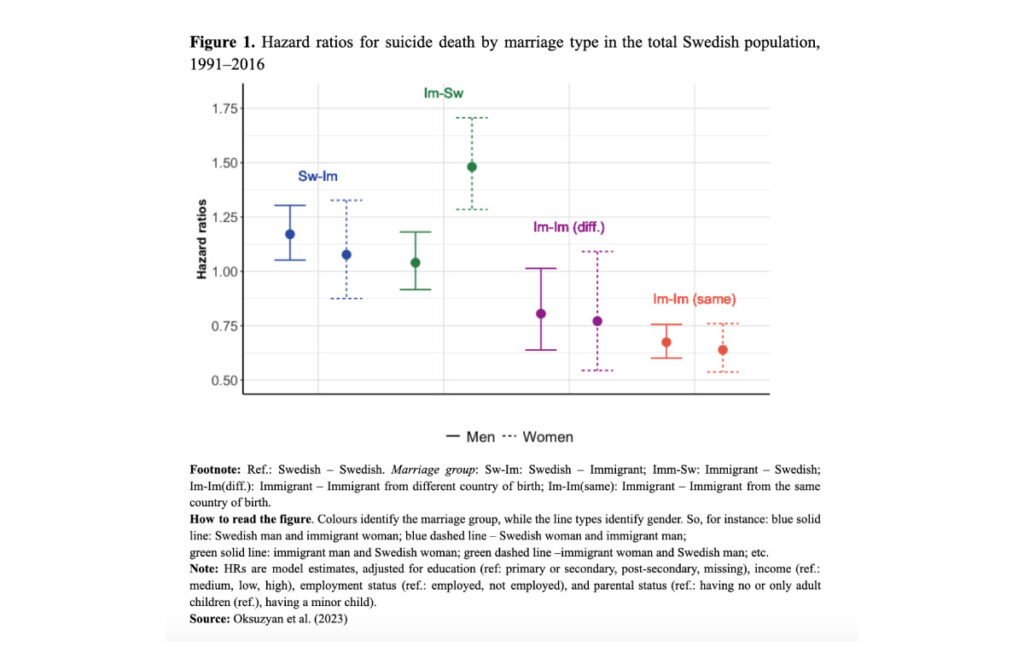

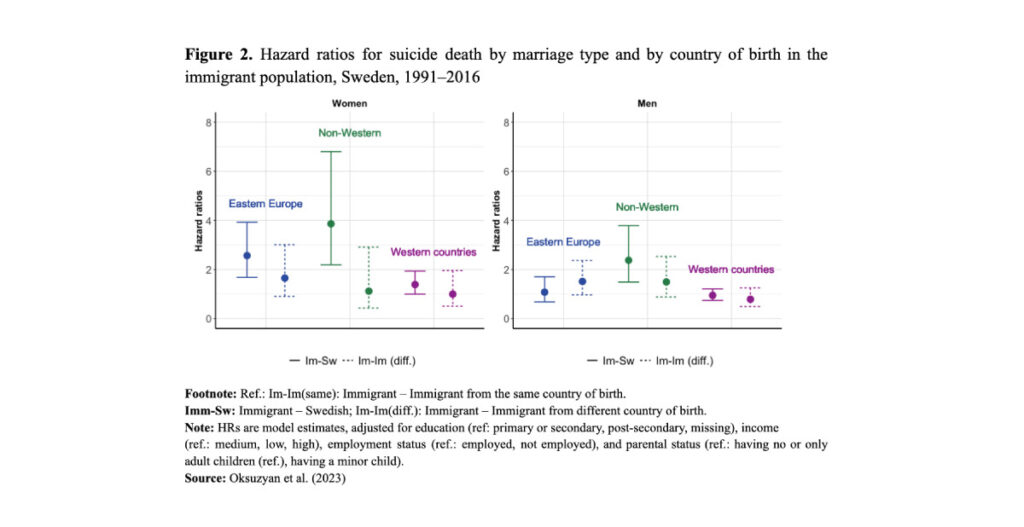

We found some evidence that intermarried people in Sweden were at greater risk of suicide. More precisely, in marriages between a native-born Swedish man and an immigrant woman, both partners were at higher risk of suicide death than in marriages where both partners were native-born Swedes (Figure 1). However, we did not find a similar elevated risk among partners in marriages between Swedish women and immigrant men. In addition, the increased suicide risk of immigrant women married to male Swedes was present only among those from non-Western countries (Figure 2). The suicide risk of intermarried immigrant women from Western nations was comparable to that of immigrant women married to other immigrants from their same country.

Why might people in marriages between a Swedish man and an immigrant woman be at greater risk of suicide? One possibility is that these marriages are characterized by more asymmetric power relations than marriages involving immigrant men and Swedish women. Immigrant men were more likely to marry “down” in terms of education when they married a native-born woman compared to when they married an immigrant woman, i.e., to trade-off their higher socioeconomic status with the “prestige” of marrying a native woman (Kalmijn and van Tubergen 2006). These unions follow the conventional gender norms that are still prevalent in Sweden and other European nations, where men are considered to be the breadwinners and women are expected to be homemakers. In contrast, there may be conflicting expectations about gender roles in binational marriages between immigrant women with a higher socioeconomic status than their local Swedish partner.

It may also be that native-born Swedish men and immigrant women with disadvantages that may increase their suicide risk, such as poorer health behaviors and mental health, are more likely to intermarry. To test for the possibility that people in these marriages have a health disadvantage and a greater risk of death more broadly, we analyzed differences in all-cause mortality by intermarriage group. However, we did not find the same elevated hazard of death for all-cause mortality among immigrant women married to native men as we did for suicide mortality.

We also found that immigrant men and women who marry an immigrant from their same origin country had a markedly lower risk of suicide relative to Swedes married to Swedes. This finding is consistent with our initial expectation that marriages involving partners from the same ethnic background share migration experiences and are healthier, on average, than native-born persons.

Conclusion

Our study provides preliminary evidence that some individuals in intermarriages between immigrants and native-born persons are at increased risk of suicide mortality. They signal the possibility that marrying someone with a different ethnic background may potentially introduce additional stressors to marriage, such as cultural conflict, marital discord, and relationship inequality, with long-term consequences for mental health and well-being.

References

Dribe, Martin, and Christer Lundh. 2008. “Intermarriage and Immigrant Integration in Sweden: An Exploratory Analysis.” Acta Sociologica 51 (4): 329–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699308097377.

Durkheim, Émile. 1897. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Edited by George Simpson. New York: Free Press. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs13524-011-0032-5.pdf.

Eibich, Peter, and Chia Liu. 2021. “For Better or for Worse Mental Health? The Role of Family Networks in Exogamous Unions.” Population, Space and Place, no. October 2020: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2437.

Gove, Walter R. 1973. “Sex, Marital Status, and Mortality.” American Journal of Sociology 79 (1): 45–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2776709.

Kalmijn, Matthijs, Paul M. de Graaf, and Jacques P.G. Janssen. 2005. “Intermarriage and the Risk of Divorce in the Netherlands: The Effects of Differences in Religion and in Nationality, 1974-94.” Population Studies 59 (1): 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472052000332719.

Kalmijn, Matthijs, and Frank van Tubergen. 2006. “Ethnic Intermarriage in the Netherlands: Confirmations and Refutations of Accepted Insights.” European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie 22 (4): 371–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-006-9105-3.

Martínez, María Elena, Kristin Anderson, James D. Murphy, Susan Hurley, Alison J. Canchola, Theresa H.M. Keegan, Iona Cheng, Christina A. Clarke, Sally L. Glaser, and Scarlett L. Gomez. 2016. “Differences in Marital Status and Mortality by Race/Ethnicity and Nativity among California Cancer Patients.” Cancer 122 (10): 1570–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29886.

Oksuzyan, Anna, Sven Drefahl, Jennifer Caputo, and Siddartha Aradhya. 2023. “Is It Better to Intermarry? Immigration Background of Married Couples and Suicide Risk Among Native-Born and Migrant Persons in Sweden.” European Journal of Population 39 (1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-023-09650-x.

Rodríguez-García, Dan. 2015. “Intermarriage and Integration Revisited: International Experiences and Cross-Disciplinary Approaches.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 662 (1): 8–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716215601397.

WHO. 2021. Suicide Worldwide in 2019. World Health Organization. Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1350975/retrieve%0Ahttps://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240026643.