Opposites attract. Unions between majority natives and marriage migrants in Sweden

Marriage with the prospect of migration may lead to new patterns of union formation in globalized marriage markets. Annika Elwert looks at characteristics and marriage patterns of majority natives who are in unions with immigrants who either lived in the country before union formation or migrated around the time of marriage, and gives insights about majority natives’ openness towards different immigrant groups in the marriage market.

Immigrant-native intermarriage is often studied in the context of immigrant integration (see, for example, Kulu & Hannemann 2020) and is regularly regarded as the final step in the assimilation process (Gordon 1964). In a recent study on Sweden (Elwert 2019), I analyse the characteristics of natives who marry immigrants as well as assortative mating patterns in the marriages of Swedes with immigrants.¹ Assortative mating refers to the characteristics of both partners in the unions, such as level of education, income, or age. Focusing on the native majority instead of immigrants gives us a better understanding of societal openness towards minorities in the majority’s marriage market. Here, I investigate whether the Swedes who are in union with “marriage migrants” differ from those who are in union with other immigrants.

Marriage migration describes the case of people who marry with the purpose of migration: their marriage takes place before or at around the same time as the act of migration. Marriage migration is an indication of a globalization of marriage markets, due for instance to international tourism and the Internet (Niedomysl et al. 2010), and gives the majority population the opportunity to “cast a wider net” for dating and marriage. For prospective immigrants, marriage migration can be seen as a path to obtaining a residence permit. Individuals from non-EU countries can obtain a residence permit in Sweden by being married or cohabiting with someone who already lives in Sweden (Swedish Migration Agency 2020).

Immigrant-native intermarriage in Sweden

Intermarriage between immigrants and natives has increased in most European countries in past decades and is closely related to the proportion of immigrants in the country (Lanzieri 2012). Currently, almost 19 percent of Sweden’s population is foreign-born, which is higher than in the U.S., the U.K. or Germany (OECD 2020). Intermarriage rates in Sweden have risen continuously since the 1970s, and the increase has been somewhat steeper for men than for women. Between 1990 and 2009, the share of immigrant-native marriages increased from 8 to 13 percent for men, but only from 7 to 9 percent for women (Elwert 2018). Previous studies have shown that new intermarriage patterns have emerged alongside the patterns of frequent marriage between Swedes and immigrants of Nordic countries. Out of every 1,000 unmarried men aged 18 and above in 2008, around six married an EU partner while 11 married a wife from outside the EU; the corresponding number for the latter in 1991 was about three (Haandrikman 2014).

About 80 percent of immigrant-native unions in Sweden occur between natives and immigrants already resident in the country; the remaining 20 percent or so are with marriage migrants (Elwert 2019).²

I contrast the two cases by analysing all the immigrant-native marriages in Sweden (incl. non-marital cohabitations with common children) that took place from 1991 to 2009.³

Findings

The results show that Swedish men who are older, have lower socio-economic status, are divorced or have children from previous relationships have higher odds of being in a union with a marriage migrant than with a resident migrant. Also, Swedish women with lower socio-economic status have higher odds than women with high socio-economic status of being in a native-marriage migrant union. The age gap between partners is also strongly associated with unions with marriage migrants for both men and women: unions with considerably younger partners (seven years or more) are relatively more frequent when marriage migrants are involved. Conversely, educational differences do not seem to play a significant role on the marriage market in Sweden.

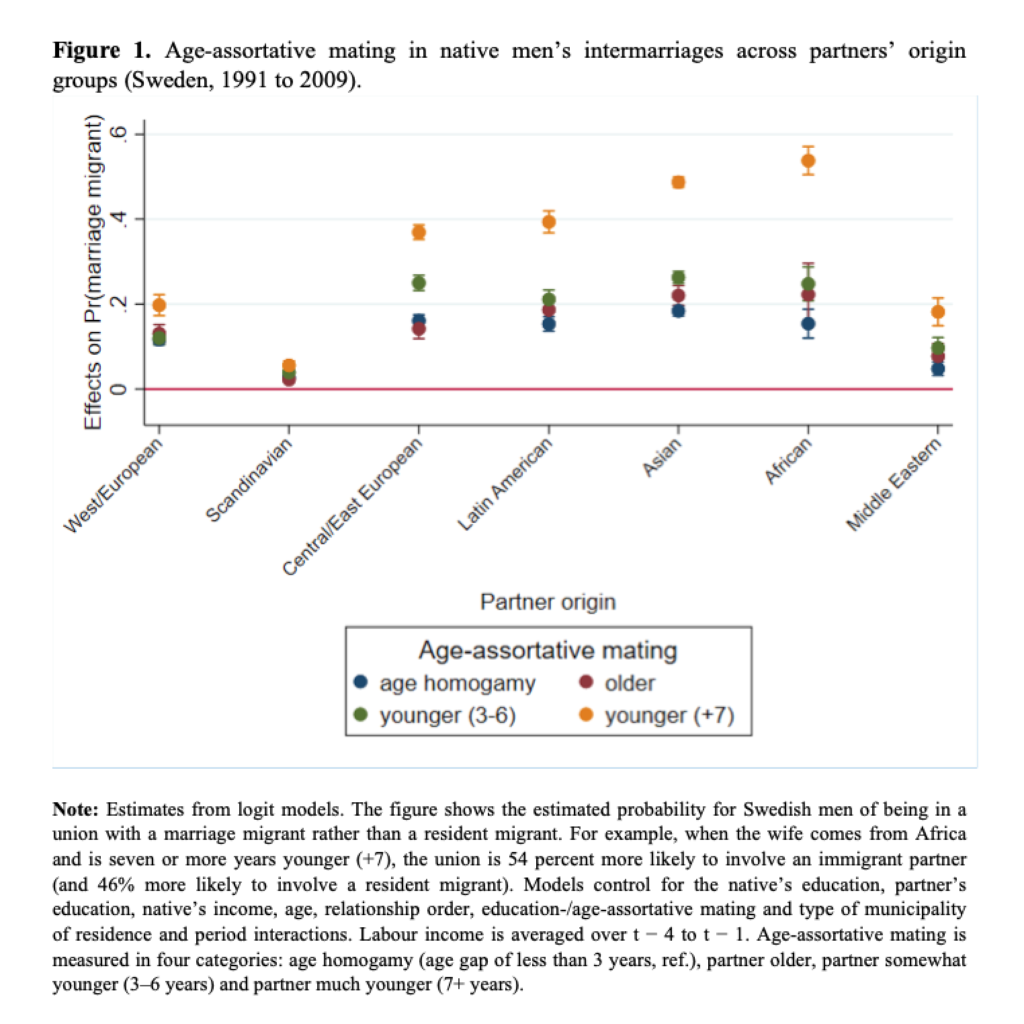

Figure 1 compares marriage migrants to resident immigrants who are in a union with a native. It displays the patterns of native-marriage migrant unions relative to native-resident migrant unions, showing that even when accounting for background factors (such as the age and education of partners, a complete list is in the figure note), unions where the immigrant partner is seven or more years younger are relatively more likely when marriage migrants are involved. However, this is not the case for all origins: the phenomenon emerges in particular with partners from central and eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia or Africa. The immigrant groups among whom unions with large age gaps are more common are also those with relatively low status in the natives’ marriage market (Osanami Törngren 2016; Potârcă & Mills 2015), and are seen as “less attractive”.

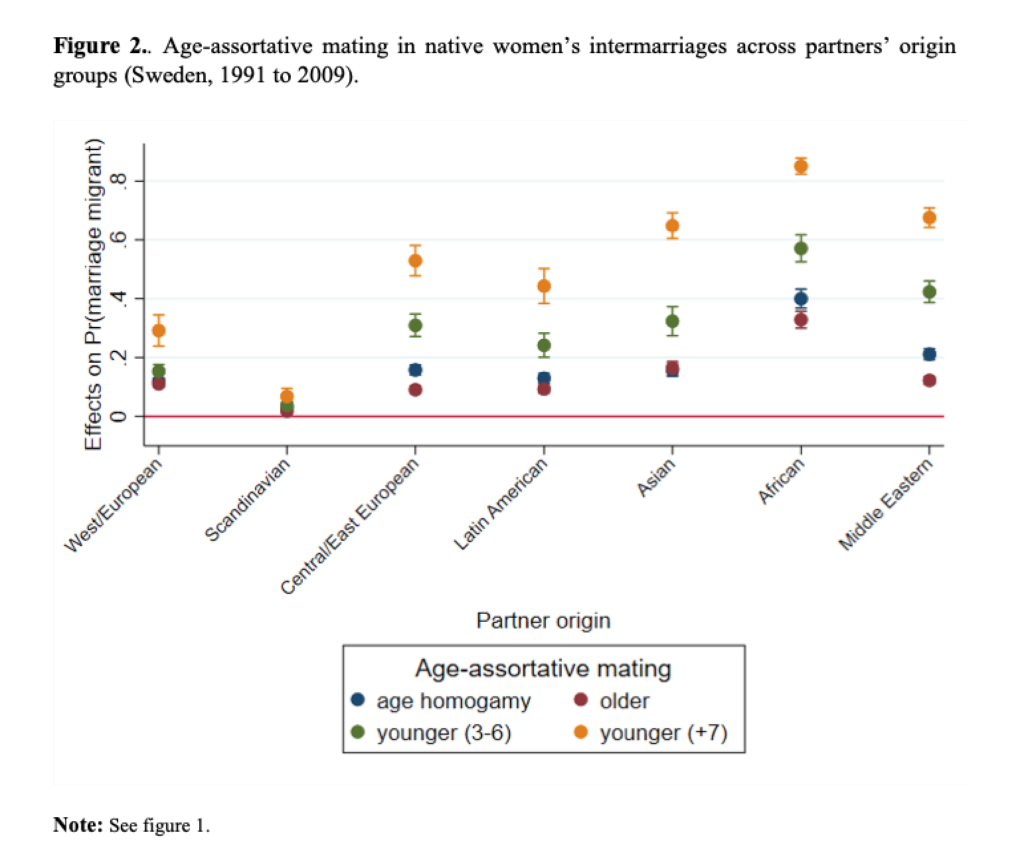

The findings of this study suggest that intermarriages involve an exchange of age and ethnic status, particularly of age and prospective residence permit. This means that immigrants belonging to immigrant groups perceived as less attractive by majority natives become more attractive if they have something to offer in exchange: age, notably.

This relationship has been found both for men and women (see Figure 2), which indicates that both value younger age in the marriage market (and not, for example, men preferring younger partners and women preferring more educated partners). This finding is yet another indication of the high level of gender equality in Sweden.

This study illustrates that the boundaries between immigrants and majority natives are manifested not only by the exclusion of immigrants of certain ethnicities from the pool of marriage partners but also by their inclusion if they have something to offer in return. In the Swedish case, this is likely to be age.

References

Elwert, A. (2018). Will you intermarry me? Determinants and consequences of immigrant-native intermarriage in contemporary Nordic settings. Lund: Lund University, Media-Tryck.

Elwert, A (2019). Opposites Attract: Assortative Mating and Immigrant–Native Intermarriage in Contemporary Sweden. European Journal of Population.

Gordon, M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion, and national origins (6th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Haandrikman, K. (2014). Binational marriages in Sweden: Is there an EU effect? Population, Space and Place, 20(2), 177–199.

Kulu, H. & Hannemann, T. (2020). Do birds of a feather really flock together? N-IUSSP.

Lanzieri, G. (2012). Mixed marriages in Europe, 1990–2010. In D.-S. Kim (Ed.), Cross-border marriage: Global trends and diversity (pp. 81–121). Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA).

Niedomysl, T., Östh, J., & van Ham, M. (2010). The globalisation of marriage fields: The Swedish case. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(7), 1119–1138

OECD (2020). Foreign-born population (indicator). doi: 10.1787/5a368e1b-en (Accessed on 19 May 2020)

Osanami Törngren, S. (2016). Attitudes toward interracial marriages and the role of interracial

contacts in Sweden. Ethnicities, 16(4), 568–588.

Potârcă, G., & Mills, M. (2015). Racial preferences in online dating across European countries. European Sociological Review, 31(3), 326–341

Swedish Migration Agency (2020). Residence permit to move to a spouse, registered partner or cohabiting partner in Sweden, accessed May 19, 2020.

Footnotes

¹ The groups under study are Swedish-born individuals with two Swedish-born parents and foreign-born individuals, i.e. immigrants. Native-born individuals with foreign-born parents are excluded. Citizenship is not observed in this data extract.

² Reason for residence permit cannot be observed in the data extract. To support the claim that residence permit is an important vehicle for these marriages, I compare the number of marriage migrants identified in the data extract with the number of adult immigrants who were granted family-related residence permits for the most common marriage-migrant countries. This comparison shows that the number of marriage migrants identified in the data accounts for 20 to 50 percent of all family-related residence permits, not all of which were granted to immigrants having married Swedish majority partners. A large proportion of immigrants with family-related permits are in unions with immigrants or second-generation immigrants.

³ Cohabiting unions without common children cannot be identified in this data extract.