On the move. The new reality for China’s migrant children

Massive internal migration in China has transformed the landscape of childhood for millions. Analyzing census data from 2000 to 2020, Mengyao Cheng, Yu Chen, Lidan Lyu, and Yu Bai find that nearly half of China’s children are now in migrant families, with more joining parents in cities than ever before. This shift in child migration patterns is reshaping family structures and challenging urban policies.

China’s economic growth has been driven by massive rural-to-urban migration. Since the economic reforms began, the migrant population has surged from less than seven million in 1982 to 376 million in 2020. Increased intra-provincial (short-range) migration, coupled with improved urban educational systems has encouraged family migration as opposed to adults moving alone (Lyu et al. 2015; NBSC et al. 2023). However, behind this evolving narrative lies a less-told story of the children (0–17 years) in family structures affected by migration, which we unveiled in a recent study (Cheng et al. 2024). We reveal how, at a time of massive internal migration, children in China navigate the complexities of family separation or relocation, facing unique challenges linked to the hukou system of household registration.

The urban migrant child boom

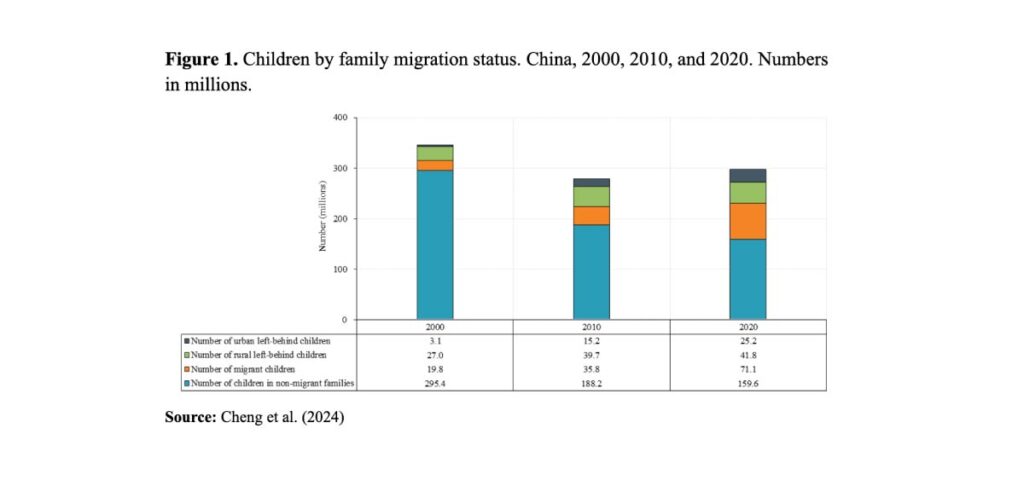

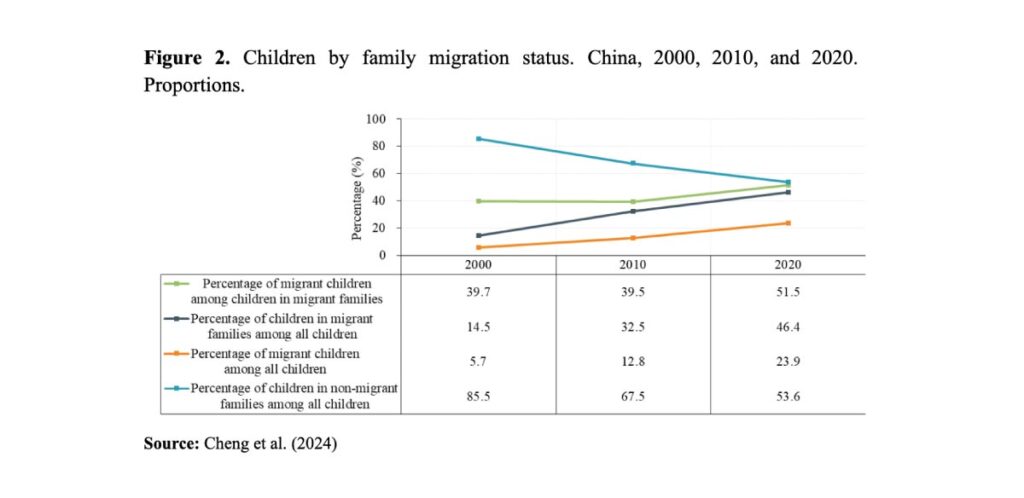

The population of children in migrant families, a group that includes both left-behind children and migrant children, has undergone huge changes. The proportion of children in migrant families surged from 14.5% in 2000 to 46.4% in 2020, with nearly one in every two children in China now living in family structures affected by migration (Figures 1 and 2).

In 2000, left-behind children far outnumbered migrant children, but things changed rapidly and by 2020, migrant children constituted 51.5% of all children in migrant families, reaching 71.1 million and accounting for 23.9% percent of China’s total child population.

Family ties in flux

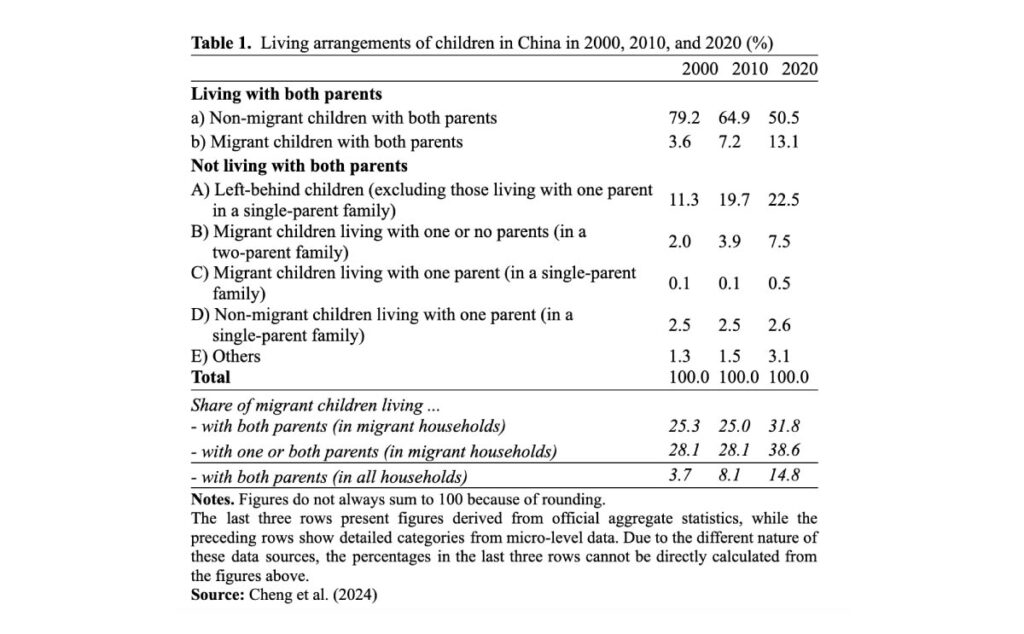

This urban migrant child boom brought with it a kaleidoscope of new family living arrangements, including, for instance, a trend towards family reunification in cities. The percentage of migrant children living with both parents at their destination increased from 25.0% to 31.8% between in 2010 and 2020 (Table 1), which indicates that more parents are now able to bring their children with them when they migrate, leading to more intact families in urban areas.

However, challenges and complexities remain. While the trend towards family reunification is evident, there is also a rise in non-traditional living arrangements among migrant children. The percentage of migrant children in two-parent families living with one or no parents increased from 2.0% in 2000 to 7.5% in 2020, indicating more complex family separations. These living arrangements vary significantly across different age groups. While 79.5% of migrant children aged 0-14 lived with both parents in 2020, a significant 10.9 million did not. The picture changes for older teens: only 24% of migrant children aged 15-17 lived with both parents, with the majority living independently or with non-parental adults.

The emergence of “left-behind child migrants”

Our most intriguing finding is the identification of a new group within the migrant children population, which we term “left-behind child migrants” (liuliu ertong – 流留儿童 – in Chinese), who have migrated across townships within a county but do not live with both parents. The move, primarily driven by the availability of schools at destination, leads to challenging family dynamics, such as separations, as parents continue to work elsewhere to finance their children’s education.

In 2020, some 14.2 million children fell into this category, a dramatic increase from just 3.4 million in 2000. In 2020, over half (57.1%) of these “left-behind child migrants” still lived with unrelated individuals or alone. This phenomenon blurs the traditional urban-rural divide. Its prevalence highlights the extent of the problems linked to the lack of stable family environments for these children, and reflects the tension between the drive for better education and the obstacles to family migration in larger cities. Moreover, it exposes the uneven rural-urban distribution of educational resources in China’s urbanization process, forcing rural families to make difficult choices.

Discussion: education as a great equalizer?

The changing pattern of child migration in China raises pressing questions about unequal access to educational resources. While policies have improved to accommodate migrant children in urban public schools, significant hurdles remain. Our findings suggest that educational aspirations are a key driver of child migration, particularly for the group of left-behind child migrants.

As China continues its rapid urbanization, the well-being of these millions of children in families affected by migration will be crucial to its social and economic future. Understanding these evolving migration patterns is the first step towards creating inclusive policies that grant all children, regardless of their migration status, equal opportunities to thrive in China’s cities.

Reference

Cheng M., Chen Y., Lyu L., Bai Y. 2024. “Children on the Move in China: Insights from the Census Data 2000–2020.” Population and Development Review, online first, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/padr.12653

Lyu L., Cheng M., Tan Y., Duan C.. 2018. “The Development and Challenges of Migrant Children Population in China: 2000–2015.” Qingnian Yanjiu [Youth Studies], (4), 1–12, 94. [in Chinese].

National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC), UNFPA China, and UNICEF China. 2023. “What the 2020 Census Can Tell Us About Children in China.” United Nations Children’s Fund China.