Older immigrants are more likely to share residence with their adult children and other family members compared to native-born older adults in the United States. Two major explanations for this pattern emerged: (1) immigrants’ cultural preferences for extended family living, and (2) immigrants’ socioeconomic disadvantage, which requires pooling resources and precludes independent living. Because direct measures of attitudes and values are seldom available and socioeconomic factors only partially explain these differences, the high rates of intergenerational coresidence among the older foreign-born are often interpreted as driven by cultural preferences or a lack of assimilation.

Immigration scholars have long pointed out that assimilation refers not only to the degree of similarity to the U.S.-born population but also to the degree of difference from the population in the immigrant-sending countries. To investigate the extent to which older immigrants’ living arrangements differ from those of older adults in their home countries, we combined data from the 2008–2012 American Community Survey (ACS) (Ruggles et al. 2015) with census data from three major immigrant-sending countries – Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Vietnam (Minnesota Population Center 2015).

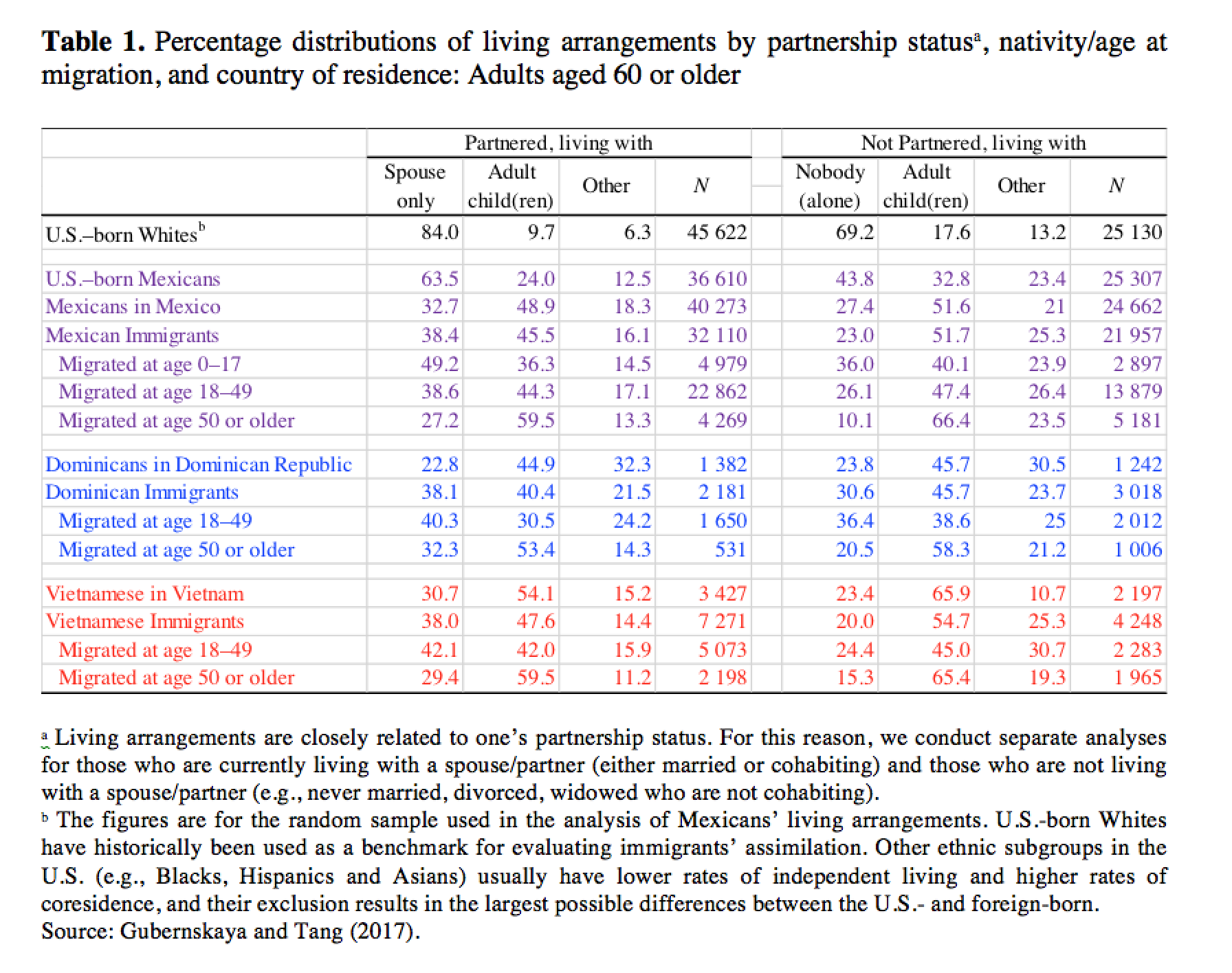

Higher intergenerational coresidence rates in emigration countries seem to support the cultural explanation. In the U.S., native-born Whites have historically been used as a benchmark for evaluating immigrants’ assimilation. As Table 1 shows, about 84% of partnered U.S.-born whites over age 60 live with a spouse only, compared with 32.7% of older adults in Mexico, 22.8% in the Dominican Republic, and 30.7% in Vietnam. Similarly, coresidence rates are relatively low among U.S.-born whites compared with older adults in Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Vietnam (9.7% vs. 48.9%, 44.9%, and 54.1%, respectively). Despite some convergence, the living arrangements of older immigrants in the U.S. resemble those of older adults in their home countries. Compared with Mexicans in Mexico, partnered Mexican-born residing in the United States are more likely to live with a spouse only (38.4 % vs. 32.7 %) and less likely to coreside with adult children (45.5 % vs. 48.9 %). The differences are somewhat larger for older Dominican and Vietnamese. But important variations in the patterns of living arrangements among the older immigrants presented in Table 1 suggest that other factors may be important.

Age at migration

Previous research has emphasized the importance of age at migration for understanding immigrant outcomes in later life. In addition to the length of exposure to U.S. society, age at migration captures opportunities for acculturation and socioeconomic incorporation, which generally decline with age (Treas 2014; Treas and Gubernskaya 2016). Younger immigrants have more opportunities to learn English, develop diverse social networks, and work long enough in the United States to be eligible for Social Security when they reach the retirement age. In contrast, later-life migrants face substantial barriers to incorporation because of the combination of advanced age, poor English language proficiency, foreign degrees and credentials, and declining health. They are often not eligible for Social Security because they lack the necessary 10 years of eligible employment history.

Figure 1 shows predicted proportions (adjusted for age, sex and education) in different living arrangements for Mexicans over age 60 residing in the United States and Mexico. Older U.S.-born of Mexican descent and older Mexican immigrants who arrived at younger ages are considerably less likely to coreside, and are more likely to live independently compared to older immigrants who arrived as adults, and especially, compared to non-immigrants in Mexico. This pattern is consistent with the immigrant assimilation explanation predicting gradual convergence of immigrants’ living arrangements toward those of the U.S.-born Americans. But older Mexicans who migrated after age 50 are significantly more likely to coreside, and less likely to live independently, than older adults in Mexico — a pattern that neither cultural preferences nor immigrant incorporation theories are able to explain.

The patterns among older Dominican and Vietnamese immigrants are very similar (not shown here). Those who migrated as adults were more likely to live independently and less likely to share residence with adult children compared to older adults in the Dominican Republic and Vietnam, respectively. But those Dominicans and Vietnamese who arrived after age 50 were more likely to co-reside and less likely to live independently than older adults in their home countries. Remarkable similarities for all three national origin groups suggest that the age of migration is one of the strongest predictors of living arrangements of older immigrants in the U.S.

Family reunification policy

The similarities of the patterns by age at migration also suggest that the context of the receiving country may be more important than cultural preferences. Older adults who migrate to the United States later in life usually do so through the family reunification provision of U.S. immigration law. Signing an “affidavit of support”, a naturalized U.S. citizen adult child can sponsor the immigration of a parent. Age-related barriers to acculturation and socioeconomic assimilation hinder late-life migrants from establishing residential independence. Being ineligible for public assistance programs during their first five years after migration increases later life migrants’ dependence on support from the family. At the same time, regardless of their country of origin, family reunification assures the selection of older newcomers who have at least one adult child with whom they can live. Thus, high coresidence among later-life migrants is driven not only by socioeconomic and cultural factors but also by the kin availability built into the immigration policy.

Policy implications

Our results paint a more complex picture of factors influencing living arrangements of older immigrants. First, despite persistent differences from the U.S.-born whites, there is a clear pattern of assimilation among children and young adult immigrants. Compared to non-immigrants in their home countries, the preferences for shared living arrangements are substantially reduced within one generation. Second, coresidence rates among later-life migrants are unusually high. This challenges purely cultural explanation and points to a previously neglected factor – immigration policies. Overemphasizing cultural factors behind old-age coresidence rates may contribute to stigmatization of the foreign-born for their lack of assimilation. It may also lead to inaccurate assessment of older immigrants’ preferences for public programs and services, shifting old age support to families.

References

Gubernskaya, Zoya and Zequn Tang. (2017). “Just Like in their Home Country? Multinational Perspective on Living Arrangements of Older Immigrants in the U.S.” Demography 54(5): 197.3-1998. doi: 10.1007/s13524-017-0604-0.

Minnesota Population Center. (2015). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 6.4 [Machine-readable database].

Ruggles, S., Genadek, K., Goeken, R., Grover, J., & Sobek, M. (2015). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Treas, J. (2014). Incorporating immigrants: Integrating theoretical frameworks of adaptation. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 269–278.

Treas, J., & Gubernskaya, Z. (2016). Immigration, aging, and the life course. In L. K. George & K. F. Ferraro (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences (8th ed., pp. 143–161). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.