Immigrants’ health tends to deteriorate over successive generations, a phenomenon known as “negative health assimilation”. Less is known about what happens to adolescents with one immigrant and one native parent. Using data from the Finnish population register, Silvia Loi, Joonas Pitkänen, Heta Moustgaard, Mikko Myrskylä and Pekka Martikainen find that these children fare worse than those born to couples where both parents are natives or immigrants.

Health conditions tend to deteriorate across immigrant generations, so that first-generation immigrants frequently have better health than second and higher order generations: a process known as “negative health assimilation” (Rumbaut 1994, Hamilton et al. 2011, Mossakowski 2015). Little is known, however, about the health of children in exogamous families, where one parent is native and the other immigrant.

Data, variables, and method

In a recent paper, we provide evidence on the role of mixed families in shaping the health gaps between different generations of immigrants in Finland (Loi et al. 2021).

The study population includes children aged 0–14 at the end of 2000, covering the 1986–2000 birth cohorts. The data derive from the Finnish population register, the Finnish hospital discharge register, and the Finnish medication purchases register. The outcomes of interest are health care records on somatic conditions, mental disorders and injuries.

• Somatic conditions include all types of conditions, such as, for instance, cancer, severe infections, asthma, epilepsy, and type 1 diabetes.

• Mental disorders include any psychopathology, such as mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use, mood/affective disorders, neurotic syndromes, behavioral and emotional disorders.

• Injuries include all types of injuries, such as burns, poisoning, and toxic effects of substances.

The study group includes the following categories of children:

• native (the reference category): born in Finland or abroad to native parents;

• first-generation immigrant: born abroad to parents who were also born abroad;

• second-generation: born in Finland to parents who were born abroad and later migrated to Finland; and

• 2.5-generation: born to one native and one immigrant parent.

We further divide children of the 2.5 generation into those who have an immigrant mother and those who have an immigrant father.

We pool all the person-years and apply logistic regressions with standard errors clustered by individual. We estimate three models for each of the outcomes. These are:

• model 1, where we study the relationship between immigrant generation and health,

• model 2, where we include family socioeconomic resources, and

• model 3, where we include stressors experienced in early childhood.

The generational health gradient

Adolescents with one immigrant and one native parent have a higher level of health care needs than adolescents whose parents are either both immigrants or both native. This holds especially for mental health problems.

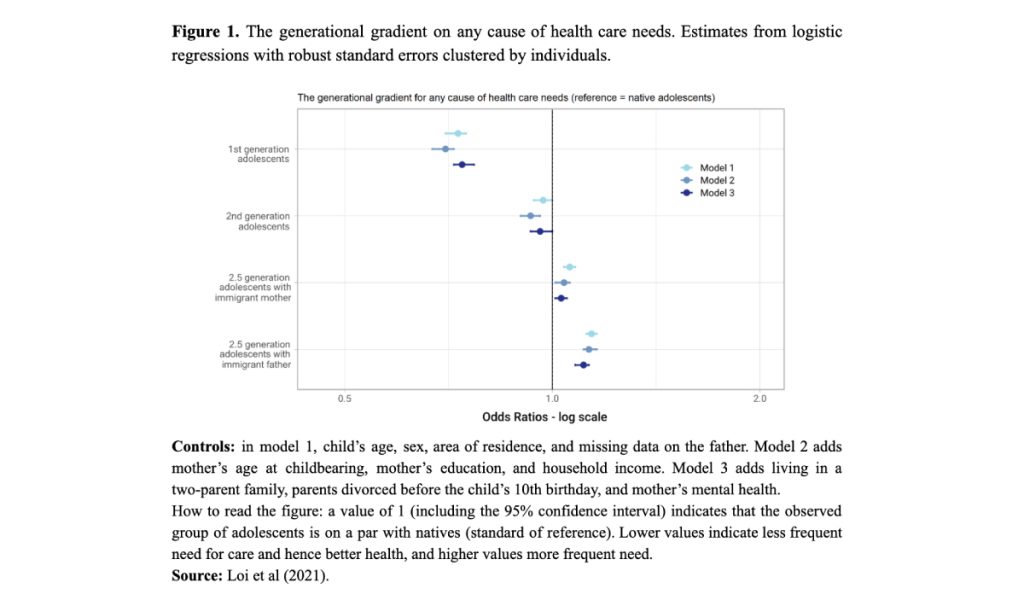

Figure 1 shows the health gaps across immigrant generations on any cause of health care need, compared to natives. In Model 1 we observe a general pattern of increasing risk of receiving care over the immigrant generations. Compared with natives, first-generation immigrants have a lower risk. This result reflects a selection mechanism: adolescents who were born abroad and immigrated with their parents benefit from a positive health selection, which is typical of first-generation immigrants (Abraído-Lanza et al. 1999; Kennedy et al. 2006). For the second generation, the risk of receiving care is similar to that of natives, while 2.5-generation children face a higher risk, especially if the foreign-born parent is the father.

In Model 2, we refine the analysis and test whether family demographic and socioeconomic characteristics contribute to explaining the health differences across immigrant generations. We include mother’s age at childbirth and education, whether information on the father is missing, and household income. Although associated with the outcome, these characteristics do not help to significantly reduce the health gaps across generations. In Model 3, we test whether stressors that occurred earlier in childhood can help explain the pattern. These stressors include whether the adolescent’s parents divorced before the his or her 10th birthday, whether the child lives in a two-parent family, and whether the mother has mental health problems. Living in a two-parent family is associated with a lower risk of receiving care, whereas parental divorce before the child’s 10th birthday is associated with poorer health. Having a mother with a mental health condition is associated with a higher risk of poor health in adolescence. Once again, all these mechanisms help explain part of the difference across immigrant generations, but not all of it.

Differences by cause of health care needs

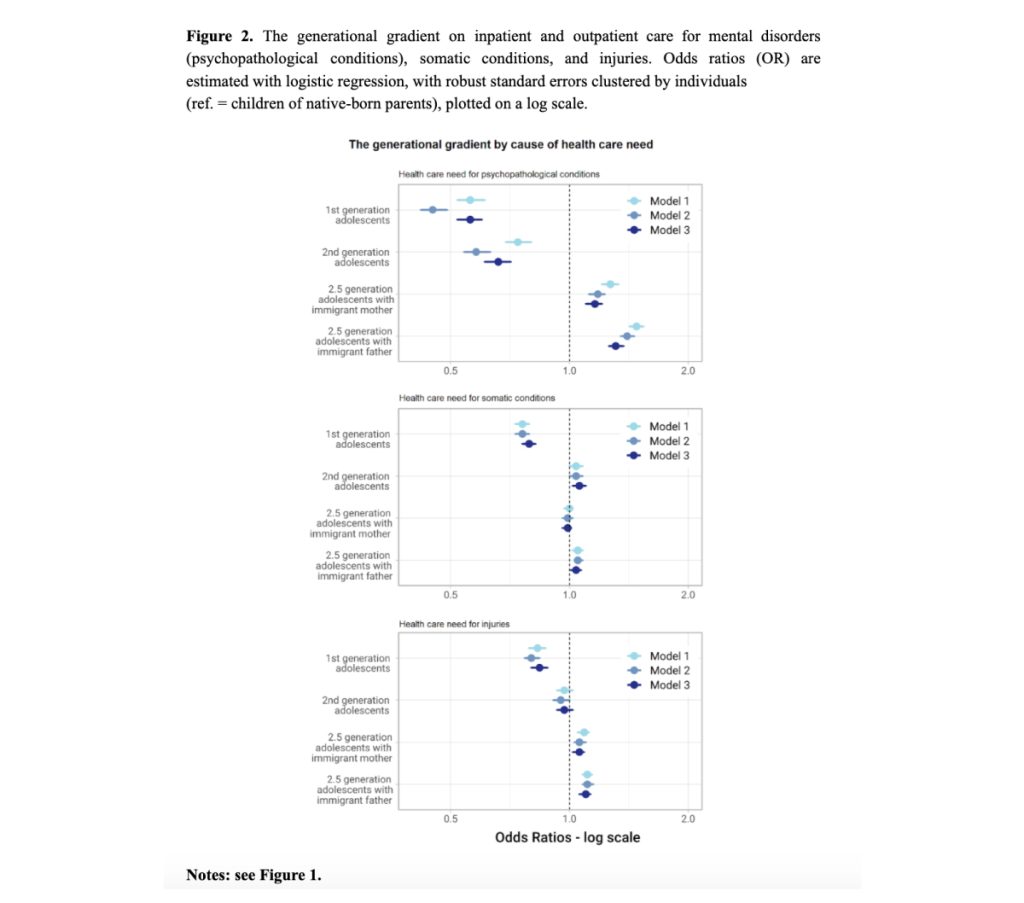

Figure 2 shows the association between immigrant generation and health care needs by cause: mental disorders, somatic conditions, and injuries. Health differences compared with natives across generations of adolescents are particularly strong in the case of mental health: children of the first and second generation have a lower risk of receiving treatment for mental disorders, suggesting a persistence of the health advantage.

Children with one native and one immigrant parent face a higher risk of mental disorders, and this relationship is stronger when the immigrant parent is the father.

Conclusions

Adolescents with one immigrant and one native parent constitute a specific health risk group. As other “explanatory” variables fail to reduce the gap with respect to the reference group, this may be a consequence either of other unobserved familial characteristics (e.g. tensions between partners) or of the broader social context in the receiving country. Adolescents with a native-born and an immigrant parent may face obstacles to integration that cause them to develop mental disorders more easily than others. These adolescents are becoming more and more numerous in immigration societies, and their health is likely to influence their later outcomes (in school, in the labor market and in social life); they probably need higher levels of care and support than they have received until now.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Max Planck Society within the framework of the research initiative “The Challenges of Migration, Integration and Exclusion” (WiMi).

References

Abraído-Lanza, A. F., Dohrenwend, B. P., Ng-Mak, S. S., & Turner, J. B. (1999). The Latino mortality paradox: A test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1543–1548.

Hamilton, E. R., Cardoso, J. B., Hummer, R. A., & Padilla, Y. C. (2011). Assimilation and emerging health disparities among new generations of U.S. children. Demographic Research, 25, 783–818.

Kennedy, S., McDonald, J. T., & Biddle, N. (2006). The healthy immigrant effect and immigrant selection: Evidence from four countries (SEDAP Research Paper No. 164). Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: Social and Economic Dimensions of an Aging Population Research Program, McMaster University.

Loi S., Pitkänen J., Moustgaard H., Myrskylä M., Martikainen P.; Health of Immigrant Children: The Role of Immigrant Generation, Exogamous Family Setting, and Family Material and Social Resources. Demography 2021; 9411326.

Mossakowski, K. N. (2015). Disadvantaged family background and depression among young adults in the United States: The roles of chronic stress and self-esteem. Stress and Health, 31, 52–62.

Rumbaut, R. G. (1994). The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented among children of immigrants. International Migration Review, 28, 748–794.