Population aging is contributing to an increase in loneliness around the world. Lauren Newmyer, Ashton M. Verdery, Haowei Wang, and Rachel Margolis explore loneliness among late-middle-aged and older adults and the reasons behind this rapid rise.

Loneliness is a crucial aspect of mental health and social well-being (Newmyer et al. 2022). It is a major concern for policymakers because of its strong negative effects on mental health (e.g., depression and anxiety), and can also lead to unhealthy behaviors (e.g., smoking and alcohol consumption), chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension and stroke), and even increased mortality risk (Domènech-Abella et al. 2019; Lara et al. 2020; Stickley et al. 2013). Loneliness is a person’s subjective feeling that their social network is deficient, whether in quality or in size (Perlman and Peplau 1981; Weiss 1973).

Older adults are at increased risk for loneliness. There is a U-shaped age pattern of loneliness: levels among adults aged 18-29 are higher than in middle age, and then decrease into middle age, before increasing again in later life starting around age 65 (Nicolaisen and Thorsen 2014). This strong correlation with age suggests that loneliness might become a larger concern in the future due to population aging.

Although much research has examined how population aging around the world will shape everything from economies and health-care systems to caregiving structures and urban planning, our research is the first, we think, to examine how it will affect levels of loneliness.

We exploit survey data from 27 countries to assess loneliness by country, age and sex using a single item. We then pair this information with projections from the UN World Population Prospects to model historical and projected changes in loneliness.

Rising tide of concern

We examined the demography of loneliness among late-middle-aged and older adults using data from surveys representing almost half of the world’s current population of people over age 50. These surveys are the Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS), the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSA), the Health, Aging, and Retirement in Thailand (HART) study, the U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS), the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS), the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Aging (KLoSA), the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS), the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), and the Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging (TILDA). As to be expected, loneliness is common among late-middle-aged and older adults around the world. In the majority of countries in our sample, more than 10% of adults in these age groups report being lonely, and in 17 of 27 countries the share was above 25%.

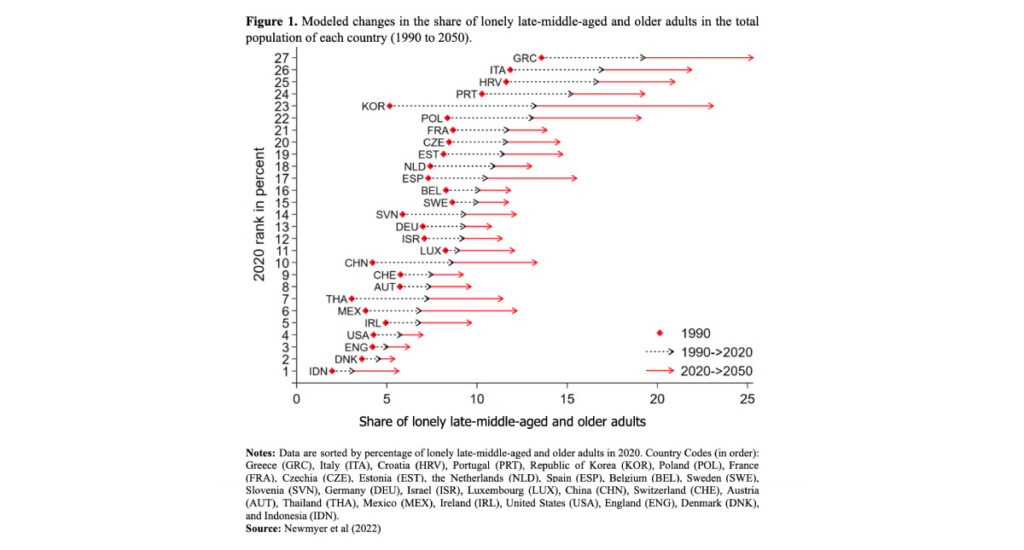

The prevalence of loneliness and the rate of population aging are two important factors determining the rising tide of loneliness around the world. Changes in the age and sex distribution of populations will lead to increases in loneliness among adults over age 50 in all countries in our sample, but with increasing variability across countries (see Figure 1 below). In some countries, like Greece, Croatia, Italy, and the Republic of Korea, lonely adults over age 50 will soon comprise a fifth to a quarter of the total population, while in others, such as Denmark, England, and Indonesia, the share is set to remain quite low.

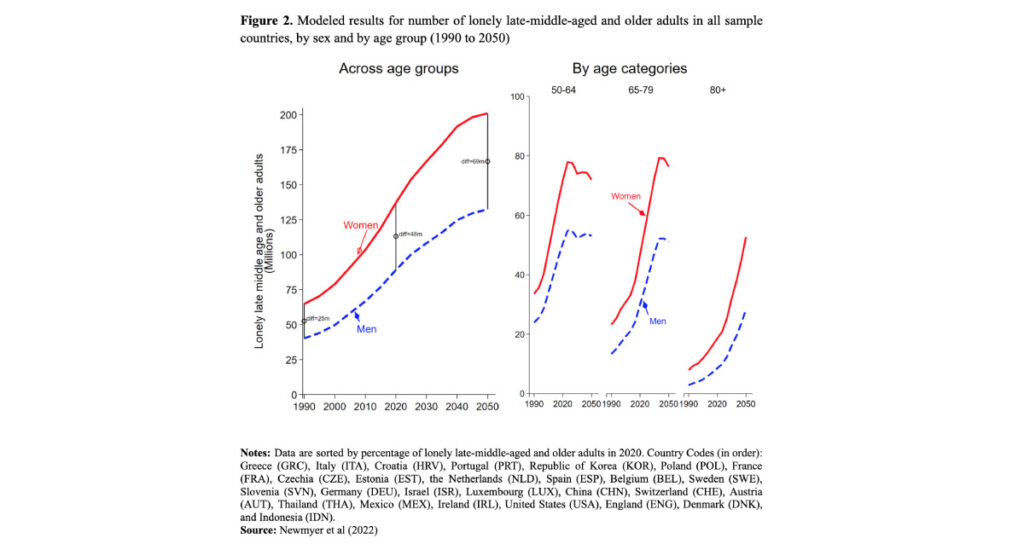

Our results show that loneliness in late middle age and older adulthood affects more women than men globally, and this gap is projected to widen in the future (see Figure 2 below).

Ways to confront challenges arising from increased loneliness

Expected demographic changes imply massive increases in loneliness at ages 50 and above. Assuming constant age- and sex-specific rates of loneliness, the number of lonely adults in these age groups in our sample countries is set to triple from 105 million in 1990 to 333 million in 2050. Opportune policy interventions aimed at families and communities should make it possible to lower this total, however. Policymakers and communities should consider investing more in programs to reduce rates of loneliness through increased social support.

References

Domènech-Abella, Joan, JordiMundó, JosepMaria Haro, and Maria Rubio-Valera. 2019. “Anxiety, Depression, Loneliness and Social Network in the Elderly: Longitudinal Associations from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA).” Journal of Affective Disorders 246: 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.043.

Lara, Elvira, Darío Moreno-Agostino, Natalia Martín-María, Marta Miret, Laura Alejandra Rico-Uribe, Beatriz Olaya, María Cabello, Josep Maria Haro, and José Luis Ayuso-Mateos. 2020. “Exploring the Effect of Loneliness on All-Cause Mortality: Are there Differences Between Older Adults and Younger and Middle-Aged Adults?” Social Science & Medicine 258: 113087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113087.

Newmyer Lauren, Ashton M. Verdery, Haowei Wang, and Rachel Margolis. 2022. “Population Aging, Demographic Metabolism, and the Rising Tide of Late Middle Age to Older Adult Loneliness Around the World.” Population and Development Review 48(3): 829-862. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12506

Nicolaisen, Magnhild, and Kirsten Thorsen. 2014. “Who are Lonely? Loneliness in Different Age Groups (18–81 Years Old), Using Two Measures of Loneliness.” International Journal of Aging and Human Development 78(3): 229–257. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.78.3.b

Perlman, Daniel, and L. Anne Peplau. 1981. “Toward a Social Psychology of Loneliness.” In Personal Relationships in Disorder, edited by M. Duck and R. Gilmour, 31–56. London: Academic Press.

Stickley, Andrew, Ai Koyanagi, Bayard Roberts, Erica Richardson, Pamela Abbott, Sergei Tumanov, and Martin Mckee. 2013. “Loneliness: Its Correlates and Association with Health Behaviours and Outcomes in Nine Countries of the Former Soviet Union.” PLoS ONE 8(7): e67978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067978

Weiss, Robert S. 1973. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation. Cambridge: MIT Press.