How old do you feel? It depends on whether you have grandchildren

The idea of a static measure of age is changing (Christensen et al., 2009; Sanderson & Scherbov, 2013). The concept of ageing is not independent of time and place, and it should take account of the improvements in health and life expectancy that have influenced how people age.

Subjective age: what is it?

In this context, self-assessments of age may capture aspects of personal well-being that escape traditional measures of health and may be more socially and psychologically meaningful than chronological age. Subjective age, i.e., how old a person feels, reflects personal evaluation of age, accounting for factors such as chronological age, role involvement and health, as well as awareness of societal age norms.

Research has shown that older people not only would like to be younger, but they also tend to feel younger than their chronological age. Determining which factors influence age perception may further our understanding of the quality of life and the mental health of the adult population.

In a recent publication (Bordone & Arpino, 2016), we used data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) conducted in the United States in 2008 to investigate the relationship between subjective age and grandparenthood. With increasing longevity and the longer period of overlap between grandparents’ lives and those of their grandchildren, the importance of the grandparents’ role has been acknowledged within the “successful ageing” framework. But grandparenthood is also a powerful reminder of a person’s ageing.

Therefore, having grandchildren might either raise or lower subjective age in relation to chronological age. While grandchildren may play the role of a premature marker of old age at an early stage of older adulthood, older grandparents tend to have a closer relationship with their grandchildren, and derive more pleasure from the time spent caring for them. They may feel younger as a result.

Among the eligible HRS respondents, we selected those aged 50 to 85 years, not living in a nursing home, and with at least one child. We excluded permanently sick or disabled respondents because these conditions have too strong an influence on subjective age and the likelihood of providing childcare.

Grandparenting pays off (at the right moment)

The results of a series of linear regression models show a magnifying effect of being a grandparent on subjective age for the youngest age groups. In particular, grandchildless men aged 50-66 and grandchildless women aged 50-64 feel about 2 years younger than their counterparts who have grandchildren, all other things being equal. Conversely, a reversed association holds for women aged 73-85 years: grandmothers in this age group feel, on average, about 2.1 years younger than grandchildless women.

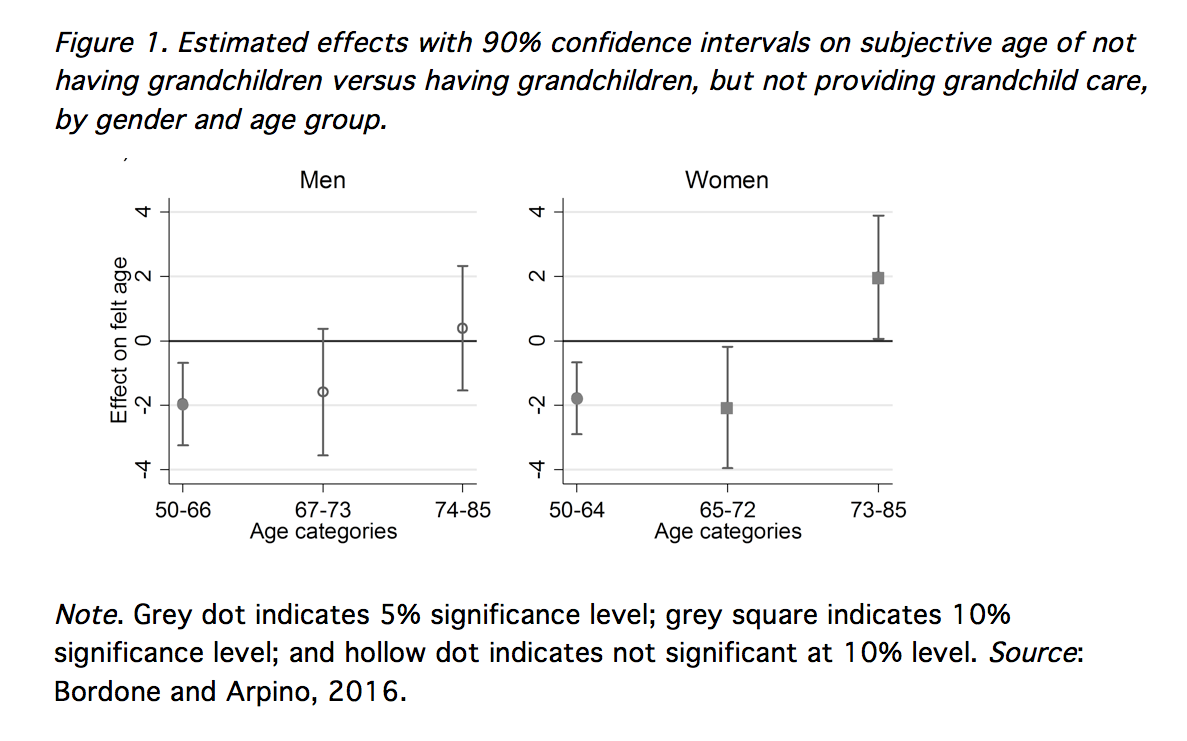

However, the association between having grandchildren and subjective age is a compound effect of several aspects related to grandparenthood. Comparing respondents without grandchildren with their counterparts who have grandchildren but do not provide grandchild care shows a “pure” effect of being grandchildless (Figure 1). In Figure 2, we compare, among those who have grandchildren, grandparents who look after their grandchildren and those who do not. Looking after grandchildren is significantly associated with lower subjective age in later life: grandfathers aged 74-85 years and grandmothers aged 73-85 years who provide grandchild care report a subjective age that is 2.6 and 1.9 years lower, respectively, than that of grandparents who do not.

The results of this study show that grandparenthood has a heterogeneous association with subjective age, moderated by chronological age. Although we do not know when grandparents in our sample had their first grandchild, the strong association between having grandchildren and subjective age, independent of care provided to grandchildren, suggests an interpretation in line with Kaufman and Elder’s reasoning (2003). On the one hand, people who “suddenly” find themselves becoming grandparents (i.e., when they may not yet be ready for it or at an age when they perhaps planned to have more time for themselves) tend to feel older. Conversely, the presence of grandchildren at older ages, when being a grandparent is more common in all cases, tends to be associated with younger subjective age.

The association between having grandchildren and a youthful subjective age in later life concerns women only (Figure 1, right panel). This is consistent with the traditional gender norms that stress the responsibilities of women as kin keepers. In later life, while men rely mainly on their wives, women are more likely to exchange support with their children, and the presence of grandchildren increases the frequency of such contacts. Grandchildlessness after age 70 could therefore increase the risk of isolation and, in turn, women’s subjective age.

How to feel two years younger

In sum, this study found a clear association between providing grandchild care and feeling younger among the oldest group of individuals considered (men aged 74-85 and women aged 73-85). For women, this combines with an additional youthful feeling linked to having grandchildren per se. These results emphasize the importance of considering the subjectivity of ageing, which, as we show, relates to both the roles that individuals hold in later life and their timing.

The magnitude of our estimated effects, when significant, is of about 2 years (the strongest effect is 2.6 years, for 74-85 year-old men who take care of grandchildren). The substantive relevance of these results lies in the finding from previous studies that subjective age rivals or even outperforms chronological age as a predictor of psychological and health-related outcomes. Given the different measures of both subjective age and health outcomes used in previous studies, it is not easy to assess whether the magnitude we find is of practical significance. Yet, evidence indicates that healthier people feel about 2 to 3 years younger than their actual age. Future studies should better assess the practical importance of the estimated effects and further explore the causality of the factors included in the analyses.

References

Bordone V., Arpino B. (2016). Do Grandchildren Influence How Old You Feel?. Journal of Aging and Health, published online on 9 December 2015.

Christensen K., Doblhammer G., Rau R., Vaupel J. (2009). Ageing populations: The challenges ahead. The Lancet, 374(9696), 1196-1208.

Kaufman G., Elder G.H., Jr. (2003). Grandparenting and age identity. Journal of Aging Studies, 17, 269-282.

Sanderson, W.C., Scherbov, S. (2013). The characteristics approach to the measurement of population aging. Population and Development Review, 39, 673-685.