Norwegian register data indicate that parents’ mental health deteriorates prior to union dissolution but improves afterwards. In contrast, Øystein Kravdal and Jonathan Wörn note, children seem to experience a continued worsening of their mental health after a break-up. There is only modest evidence of poorer physical health before the dissolution, but a clear adverse post-dissolution trend emerges in non-infectious physical diseases, especially among mothers.

The dissolution process

Several studies have shown that partnered individuals have relatively good health (Kravdal, Wörn and Reme 2022), especially if the relationship quality is high (Robles et al. 2014). Unfortunately, for many couples, the relationship becomes less rewarding after some time together and they may even struggle with serious disagreements or conflicts. At some point, at least one of the partners may feel that life, after all, would be better outside the union and take the decision to separate. Presumably, most parents take the expected consequences for their children into account in such deliberations.

After the break-up, there will obviously be some relief from the tension that triggered it, but new conflicts may arise, about dividing up property or the children’s living arrangements, for example. Additionally, there may be setbacks such as financial hardship, childcare issues, or distress because of moving to another area. In some cases, these problems may be persistent or even get worse over time, although the overall life situation may still be better – at least for some of the family members – than if the union had remained intact. In other families, the problems may wane as new sources of support and emotional satisfaction are found, and after some time life quality is perhaps not much lower than before the relationship problems started. This kind of temporary difficulty is often referred to in the divorce literature as a “crisis response”, as opposed to the more “chronic strain” that may be experienced (Amato 2000).

Such changes in relationship quality and life circumstances during the years before and after a union dissolution may have implications for the health of both parents and children, and a huge number of studies have addressed this issue. However, many factors influence both union dissolution likelihood and health, and even the investigations that have taken this into account in relatively advanced ways have provided rather mixed evidence.

Union dissolution and mental health in Norway

In a recent study, we estimated how marital separation and dissolution of consensual unions affected the health of Norwegian parents and their first child if the child was no older than 18 years at the break-up (Kravdal and Wörn 2023). The analysis was based on nationwide register data, and the annual number of consultations with general practitioners (GPs) between 2006 and 2018 was used as a health indicator. In total, households were observed over about 800,000 years. We controlled for all measured and unmeasured factors that are constant over time by comparing the number of consultations at different times before and after the break-up for the same individual.

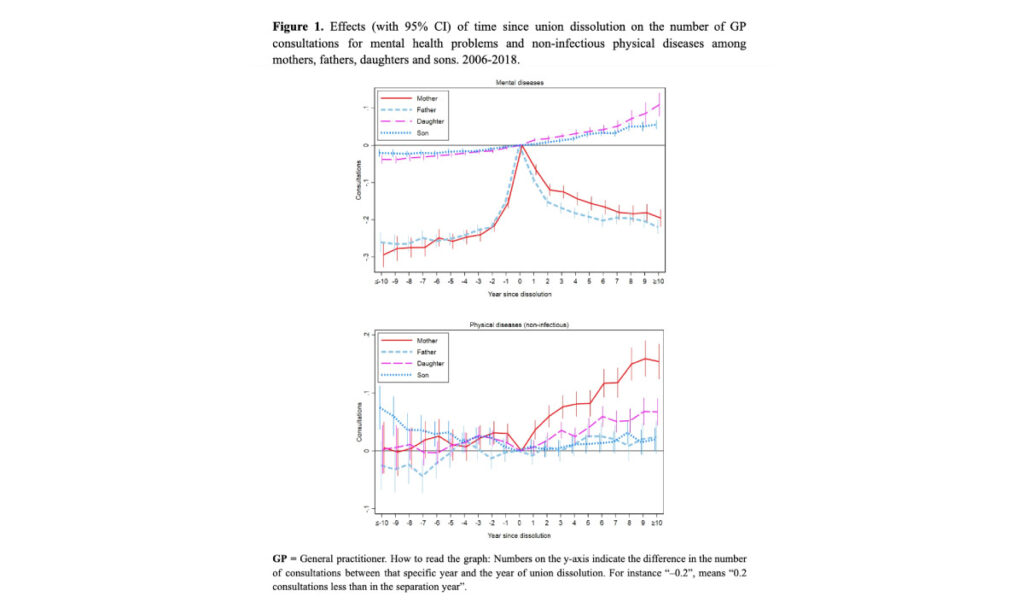

As one might expect, the number of consultations where the patient was diagnosed with a mental health problem increased among both mothers and fathers for some years before a union dissolution (Figure 1), when the relationship quality typically deteriorates. The numbers dropped immediately afterwards, although within the post-dissolution decade that could be studied, they remained higher than long before the dissolution (e.g. four years or more). In the long run, mothers appeared to be slightly more adversely affected than fathers.

Consultations for mental health problems before the dissolution also increased for children, although less so than for parents (also after taking into account the generally fewer consultations for such problems among children; not shown). At this stage, the children are possibly influenced by changes in parental behaviour caused by their relationship problems. Interestingly, this increase in consultations for mental health problems continued and even intensified after the break-up. The patterns were similar for daughters and sons. At first sight, this may suggest that, while a break-up comes as a (partly expected) relief to the parents, it harms the children. In other words, the children’s interests may not have been taken sufficiently into account in the decision-making. This is not necessarily the case, however, as these children might have experienced even worse health consequences had their parents stayed together.

The general pattern did not vary much across married or cohabiting couples.

Physical health

In contrast to the findings for mental health, there was almost no increase in consultations for non-infectious physical diseases before a dissolution for any of the family members. This is consistent with the hypothesis that effects on physical health are less immediate than effects on mental health (Hughes and Waite 2009). However, numbers of consultations started increasing later, for mothers especially, with a smaller increase or stability for the others. The upturn among mothers was not much smaller than their pre-dissolution increase in consultations for mental health problems, but because mothers in general consult GPs three times more often for physical than for mental illnesses, the increase in consultations for physical health problems is much smaller in relative terms. A dip could be seen among mothers in the break-up year, but this was entirely a result of musculoskeletal ailments (not shown), which perhaps were underdiagnosed that year or reported as mental health problems.

The more adverse trend for mothers than fathers is noteworthy. Although one might expect mothers to have more economic problems after a break-up, and also to be more burdened by childrearing, other problems may be felt more strongly by fathers, and earlier studies have not given a clear picture about the difference between the two parents. The trends in consultations suggest that children’s physical health is also negatively affected by their parents’ break-up. This seems to hold especially for daughters, although gender differences are not always clear, and appear to be model-sensitive.

One might expect life changes before and after dissolution to affect social interaction patterns, and perhaps to increase vulnerability to infections because of sleep deprivation or other stress-induced health burdens. However, the overall conclusion was that the number of consultations for infections remained quite constant through the dissolution process (not shown). The clearest exception was a temporary surge in the break-up year and subsequent year for mothers.

Conclusion

In summary, our analysis indicates that the health of the entire family may be influenced by a dissolution process, although the break-up itself may give certain health benefits. It is important to note that even if the parents appear to be on a favourable health trajectory after the break-up, that is not necessarily the case for the children.

References

Amato, Paul R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and Family 62(4): 1269-1287.

Hughes, Mary E., and Linda J. Waite (2009). Marital biography and health at mid-life.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50(3): 344-358.

Kravdal, Øystein, Jonathan Wörn, and Bjørn-Atle Reme (2022) Mental health benefits of cohabitation and marriage: A longitudinal analysis of Norwegian register data. Population Studies (online first) www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00324728.2022.2063933

Kravdal, Øystein, and Jonathan Wörn. (2023). Mental and physical health trajectories of Norwegian parents and children before and after union dissolution. Population and Development Review online first. http://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12530Robles, Theodore F., Richard B. Slatcher, Joseph M. Trombello, and Meghan M. McGinn. (2014). Marital quality and health: a meta-analytic review,” Psychological Bulletin 140(1): 140-187.