Women’s employment 1996-2016: US vs Europe

Among OECD countries, the United States was once a leader in women’s labor force participation, but is now a laggard. Jennifer Hook and Eunjeong Paek compare trends in American and European women’s employment to investigate why the American gender revolution has stalled.

In 1990, American women’s labor force participation (LFP) rate ranked sixth highest among 21 OECD countries, at 74% (among women aged 25-54 years), but increases soon stalled. In 2016, this rate was unchanged and the United States had fallen from 6th to 18th place, leading to the diagnosis of a “stalled gender revolution” (England et al. 2020). In this article, derived from Hook and Paek (2020a), we evaluate the performance and outlook of the United States in terms of women’s LFP rates, by comparison with 17 European countries.

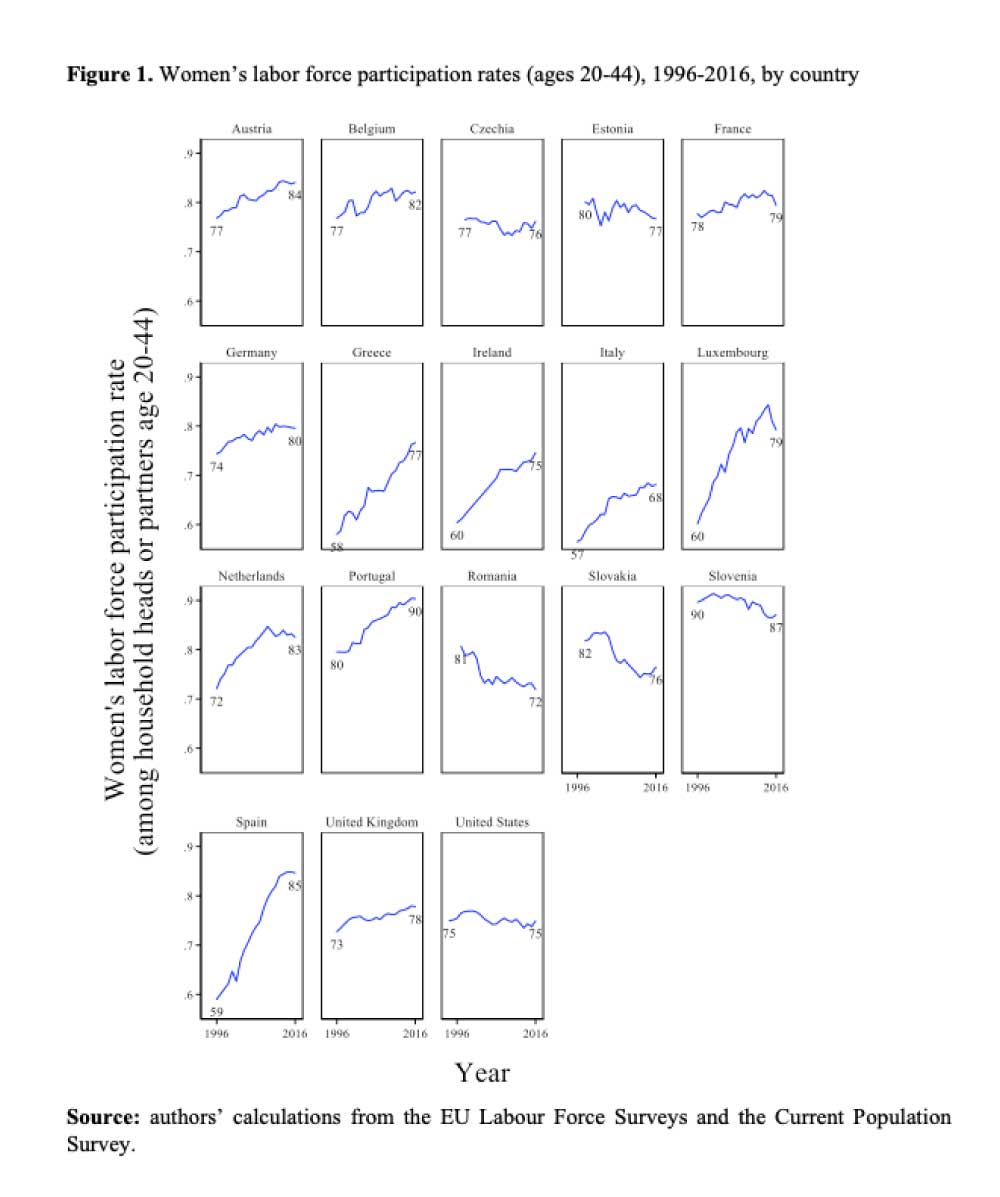

To understand change—or the lack thereof—in women’s LFP rates, we compared trends in the U.S. and 17 European countries from 1996 to 2016 (Figure 1; only women aged 25-44 years are covered). Most countries post an increase in women’s labor force participation, with the exception of former socialist countries, where it declined, and the United States, which shows stagnation.

We further analyzed trends by grouping women according to three characteristics found to independently influence women’s employment: being in a partnership, being a mother and being college-educated. We examined these characteristics separately and jointly (e.g. partnered mothers without a college degree). We were particularly interested in the LFP of mothers, so our analysis is limited to women aged 20-44 because the data do not allow us to identify mothers no longer living with their children. This comparison revealed an important piece of the puzzle.

Trends

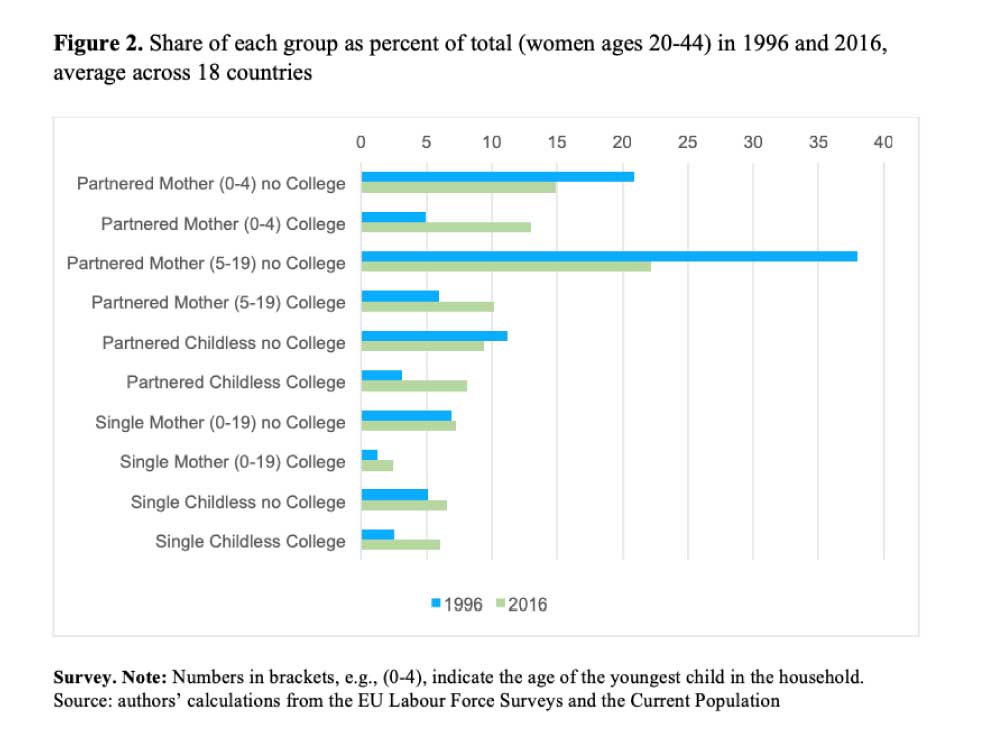

Although the share of partnered mothers without college degrees has decreased over time, they were the largest group of women (age 20-44) across countries in both 1996 and 2016, as shown in Figure 2.

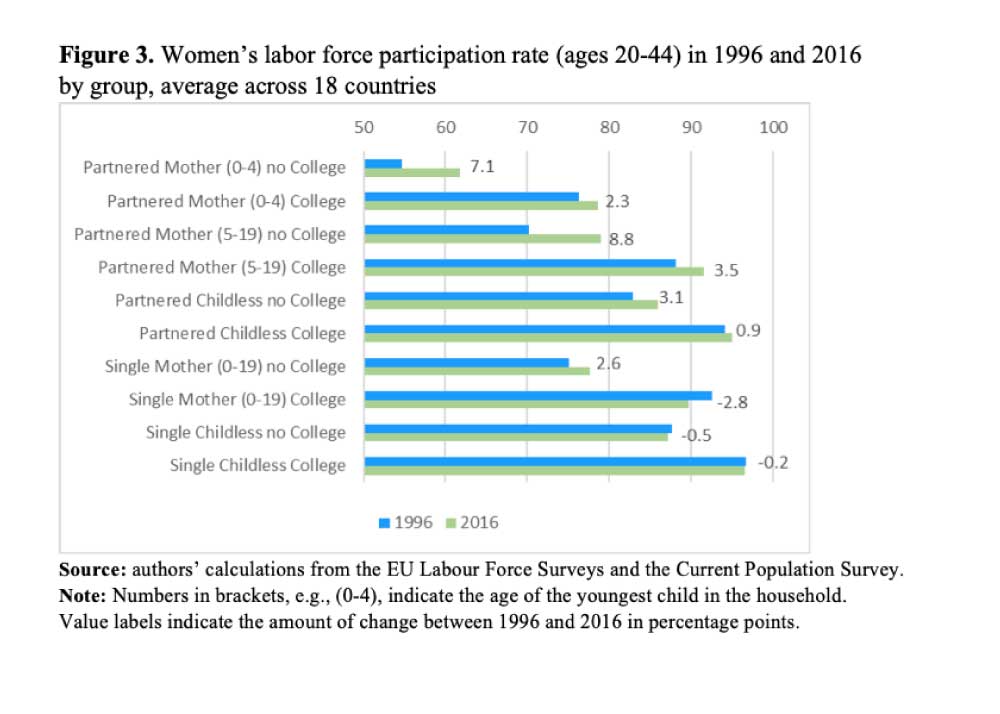

They were also the main contributors to growth in women’s labor force participation in most countries, as shown in Figure 3. On average across 18 countries, the LFP rate of partnered mothers without a college degree increased by 8.8 percentage points over the period for mothers of older children and by 7.1 points for mothers of younger children. In contrast, the LFP rate of partnered mothers with a college degree and of single mothers without a college degree increased much less, by 2 or 3 percentage points.

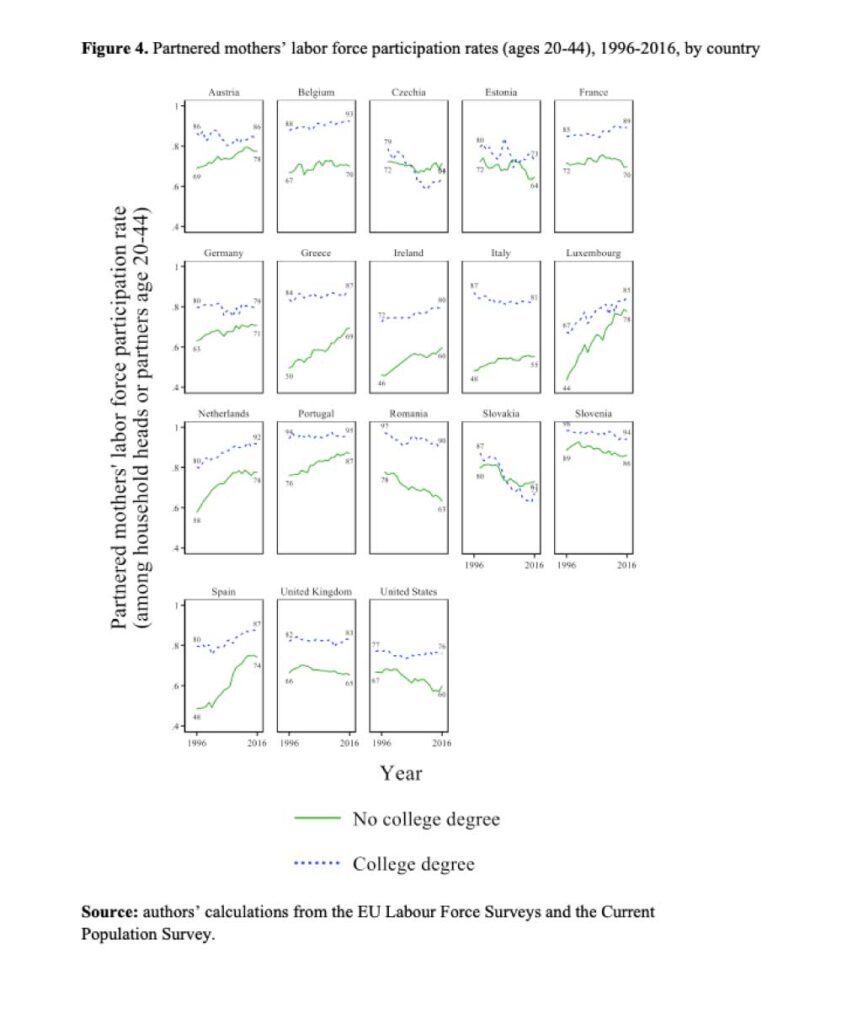

Women’s LFP rate varied dramatically across countries, however. In a large group of European countries, it increased sharply because partnered mothers without college degrees went to work and did so in large numbers. This did not happen in the United States, however, and the country started to lag behind. Figure 4 replicates Figure 1, but is restricted to partnered mothers, and shows trends separately by women’s educational attainment.

Why did trends diverge?

There are several possible reasons why large numbers of partnered mothers without college degrees went to work in some countries but not in others.

First, mothers partnered with low-earning men, likely without a college education themselves, may have faced increasing economic pressure to join the labor force. Higher levels of income inequality increase labor force participation among mothers of young children without a college degree, suggesting that economic necessity is a push factor (Hook and Paek 2020b), but this does not explain why the US stagnated during this period.

Second, we may simply be observing the diffusion of the LFP from higher- to lower-educated women. That is, once countries attain “high” labor force participation for mothers with college degrees, there is little room for this group to make further advances. Yet, LFP rates among college-educated mothers in countries such as the Netherlands and Spain were similar to those of the United States in the 1990s but are now roughly 10 to 15 percentage points higher, as shown in Figure 4. Thus, this perspective is scarcely helpful for understanding why the United States fell from 6th to 18th place.

Third, and probably more convincingly, countries that mobilized mothers without college degree may have pushed the right combination of labor market and family policy levers to encourage their participation, such as providing early childhood education and care, or rights to part-time work. We do not know yet what specific policies or policy packages are most responsible for this growth, in part because research has rarely focused on partnered mothers without college degrees. We do know, however, that public spending on early childhood and childcare provides the biggest boost to employment for mothers without a college degree, especially in countries with high levels of income inequality like the United States (Hook and Paek 2020b). Without affordable childcare, the costs of working may not outweigh the benefits.

Looking to the future

Researchers, journalists, and policy-makers interested in gender inequality in employment currently focus disproportionately on the careers of college-educated mothers in professional occupations and, to a lesser extent, on the employment challenges faced by single, lower-educated mothers. Yet, partnered mothers without college degrees, the largest group of women and those driving trends in women’s labor force participation, receive relatively little attention. Our understanding of gender inequality in employment would benefit from a greater focus on the “missing middle,” mothers who are neither college-educated professionals nor poor (Williams and Boushey 2010; Skocpol 2000).

We anticipate that the employment prospects of partnered mothers without college degrees, particularly in the United States, will be especially hard-hit by COVID-19, and we do not expect this trend to reverse quickly. Early research suggests that mothers are disproportionately pushed out of the labor force by closures of childcare centers and schools (Rasheed and Morrissey 2020), and this problem may well be particularly acute for mothers without a college degree who have fewer resources to meet childcare needs (e.g., nannies, learning pods). Mothers without college degrees are also more affected by increased unemployment. Greater investments in policies that support working mothers are needed.

References

England, Paula, Andrew Levine, and Emma Mishel. 2020. “Progress toward Gender Equality in the United States Has Slowed or Stalled.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(13): 6990-97.

Hook, Jennifer L., and Eunjeong Paek. 2020a. “A Stalled Revolution? Change in Women’s Labor Force Participation During Child-Rearing Years, Europe and the United States 1996–2016.” Population and Development Review. DOI: 10.1111/padr.12364

—. 2020b. “National Family Policies and Mothers’ Employment: How Earnings Inequality Shapes Policy Effects across and within Countries.” American Sociological Review 85(3):381-416. DOI: 10.1177/0003122420922505

Malik, Rasheed and Taryn Morrissey. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Forcing Millennial Mothers Out of the Workforce.” Center for American Progress.

Skocpol, Theda. 2000. The missing middle: Working families and the future of American social policy. WW Norton & Company.

Williams, Joan, and Heather Boushey. 2010. “The Three Faces of Work-Family Conflict: The Poor, the Professionals, and the Missing Middle.” Center for American Progress. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.2126314