The transition to parenthood in Germany often results in a more gendered labor division, with women reducing paid work and increasing housework. Maria Hornung and Chiara L. Comolli examine how perceptions of fairness in labor division change around childbirth, finding that mothers increasingly feel disadvantaged while fathers’ perceptions remain stable.

In many contemporary societies, the division of paid and unpaid work in different-sex couples remains gendered, with women handling most housework and men contributing more paid labor (Goldscheider et al., 2015). Despite this, both men and women often perceive the arrangement as fair. In Germany, the arrival of a first child significantly changes this division. Women typically reduce their paid work and do more housework, while men increase their paid work hours. In a recent study (Hornung & Comolli, 2025), we explore how becoming a parent shapes women’s and men’s perceptions of fairness in the division of labor.

The transition to parenthood is a process

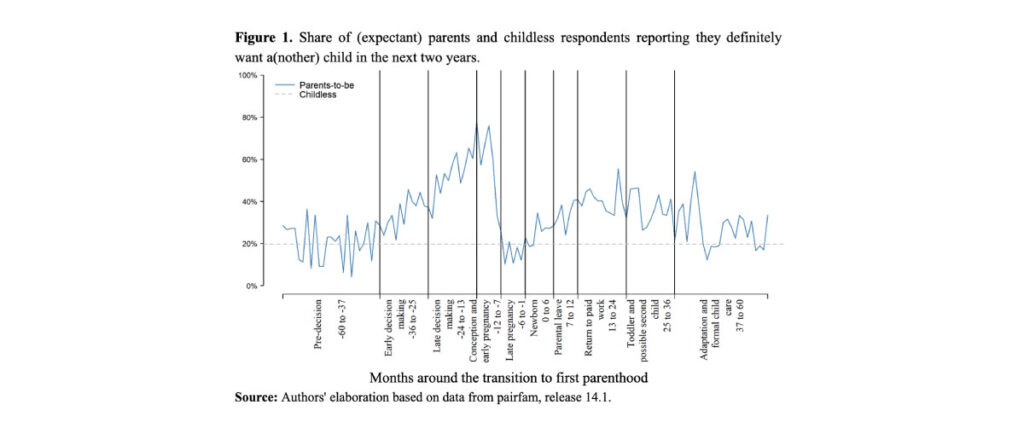

In Germany, most pregnancies are planned, and a couple’s decision to have a child usually starts to unfold well before conception. The blue line in Figure 1 shows how likely future parents are to report that they definitely want to have a child within the next two years, extending from five years before to five years after they actually have a child. In the period five to three years before childbirth, future parents’ intentions are very low and similar to those expressed by childless individuals not intending to have a child (dashed line in Figure 1). In this phase, we can assume that these prospective parents have not yet decided to have children. However, three years prior to childbirth, the percentage expressing a strong desire to have a child begins to rise, reaching 60% two years before childbirth.

The decision to have a child is influenced by preferences and intentions, negotiations between partners, anticipation, and planning. Once a child is born, parents may feel overwhelmed by their new responsibilities, have less free time, and face changing work dynamics. In the first months after childbirth, parental leave can help parents adjust to the baby’s arrival, but when it ends, and most mothers go back to work, couples must navigate new routines and balance their professional commitments with family responsibilities.

Fairness perception around the transition to parenthood

Such different challenges faced by parents around childbirth raise questions about the perceived fairness of the division of paid and unpaid work in their partnership during all phases surrounding the transition to parenthood, starting well before and possibly lasting long after childbirth itself, and how this may differ between men and women.

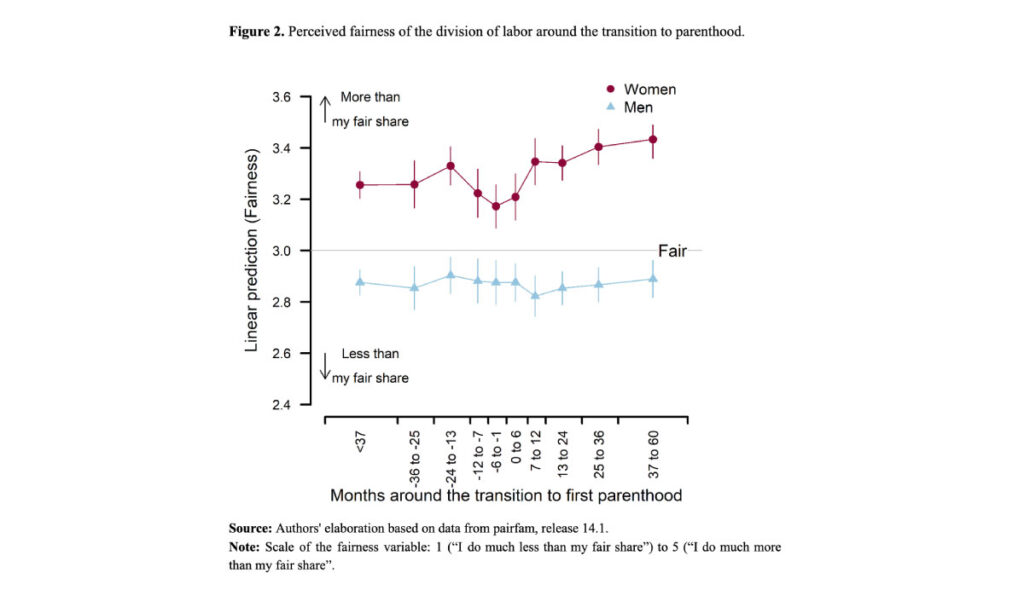

Figure 2 illustrates that mothers report a fairer perception during pregnancy and up to six months post-birth compared to the period before deciding to have a child. After that time, the belief that they are doing more than their fair share of the labor in the couple grows and continues to strengthen as the child gets older. Mothers of children aged 3 to 5 perceive the division of labor as significantly more unfair to them than before they chose to have children.

Fathers, instead, consistently perceive that they contribute less than their fair share and this perception varies little during the years surrounding the first birth, indicating that this transition has a lesser impact on men than on women.

Conclusions

Mothers’ perceptions of fairness in the division of labor during the transition to parenthood vary based on when the evaluation takes place. Around conception and during pregnancy, expectant mothers tend to view the division of labor as fairer than in the time before deciding to have a child. However, after parental leave ends a growing sense of doing more than their fair share emerges.

Our study demonstrates the importance of measuring mothers’ perception of fairness well before conception; otherwise, the negative impact of motherhood on perceived fairness may be overestimated. Yet, we also emphasize that examining not only the short-term effects of childbirth on perceived fairness but also the medium- and long-term consequences is essential, as we do not see a return to earlier levels of fairness even five years after childbirth.

Two additional findings from our study are worth mentioning. First, the transition to fatherhood appears to have little or no impact on men’s perceptions. Second, the outlined trajectories of perceived fairness concerning parenthood among mothers and fathers only partially depend on actual changes in the division of housework and paid work between partners. The increase in housework may go unnoticed by men, or the unequal distribution of responsibilities may be viewed as less acceptable if a child is present. These findings raise important questions for future research about the factors shaping perceptions of fairness and the mechanisms linking parenthood to changes (or lack thereof) in fairness perception.

References

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The Gender Revolution: A Framework for Understanding Changing Family and Demographic Behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00045.x

Hornung, M., & Comolli, C. L. (2025). The perception of fairness in the division of labor around first childbirth in Germany. Genus, 81(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-024-00239-8

Sources figures 1 and 2 – https://www.pairfam.de/en/