How retirement policies and demographic change influence China’s gender labor force gap

The gender gap in labor force participation is expanding in China, for various reasons, among which scarcity of affordable public childcare and growing discrimination against women in the labor market. Part of the explanation, Kai Feng argues, lies in the rigidities and discrimination of the Chinese pension system, which forces women to retire earlier than men.

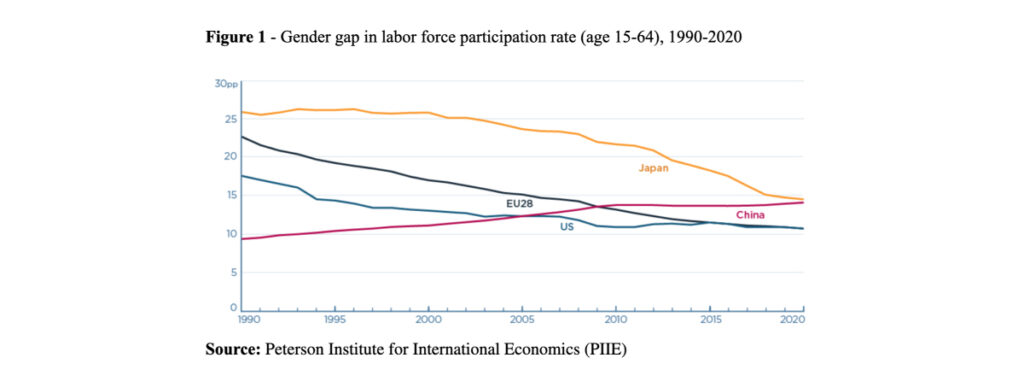

China, once renowned for its high women’s labor force participation, is now experiencing an unexpected downturn. While the gender gap in labor force involvement is narrowing at global level, it is expanding in China (Figure 1)

During Mao’s era, the labor force participation rate for women was exceptionally high, driven by the radical ideology that “women hold up half the sky” and by massive social mobilization to promote female employment. The planned economy of the time also meant that both women and men had little choice but to work for a living. With the advent of market reforms in 1978, not working became a viable option for many. In addition, subsequent institutional shifts have erected significant barriers for women seeking to join or stay in the workforce.

Why has the gender gap in labor force participation widened in China?

Numerous studies, as summarized in Ji et al (2017), suggest that the reduction in affordable public childcare —previously widely available — combined with escalating discrimination against women since the economic reforms, are contributing to this widening gap. Drawing from these findings, researchers recommend policies to enhance access to cost-effective childcare, to curb workplace discrimination against women, and ensure equal rights for women and men, irrespective of women’s fertility behaviors or intentions.

In a recent study (Feng 2023) I highlight an often-overlooked factor: China’s gender-based retirement policy. Under this policy, established in the 1950s with the intention of “protecting” female workers (some argue it was a legacy of the Soviet model), women are expected to retire at either age 50 or 55, depending on their occupations, while men retire at 60. This policy has remained untouched, even as women’s life expectancy has risen and their presence in higher education and the workforce has significantly expanded.

Increased women’s labor force participation after age 50, but composition effects prevail

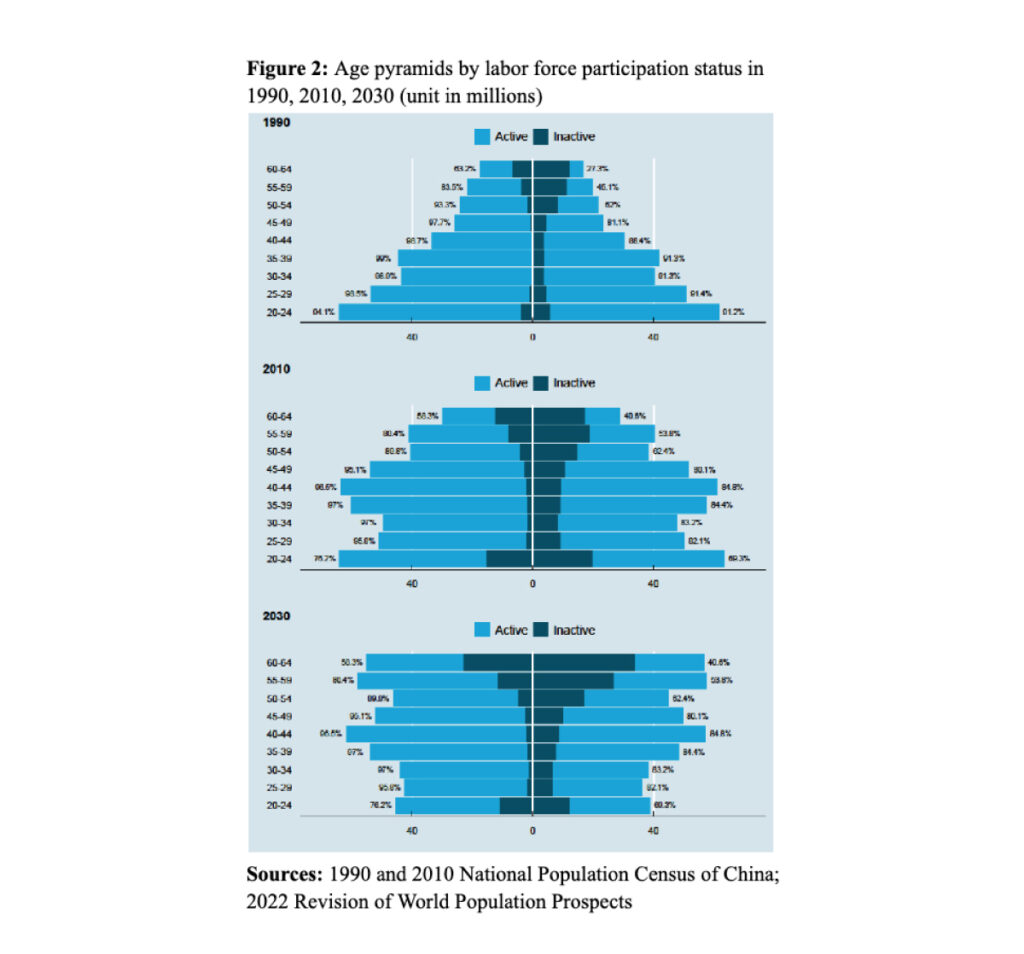

A significant factor contributing to the observations is the shift in population age composition. As a larger portion of the population reaches retirement age, a higher number of women than men exit the workforce (Figure 2).

Women’s labor force participation rate above age 50 actually increased between 1990 and 2010, (as shown by the percentage on the top of the bar), together with the population aged 50 and over. In 1990, the majority of the working-age population consisted of younger age groups, with women aged between 50 to 64 represented only 19% of the entire workforce (ages 20 to 64). This percentage grew to 24.5% in 2010 and is anticipated to reach 37.2% by 2030.

These demographic shifts are expanding the gender gap in labor force participation over the years. If labor force participation rates remain consistent with the 2010 data, the projected age structure for 2030 suggests an even more pronounced gender disparity in labor force participation.

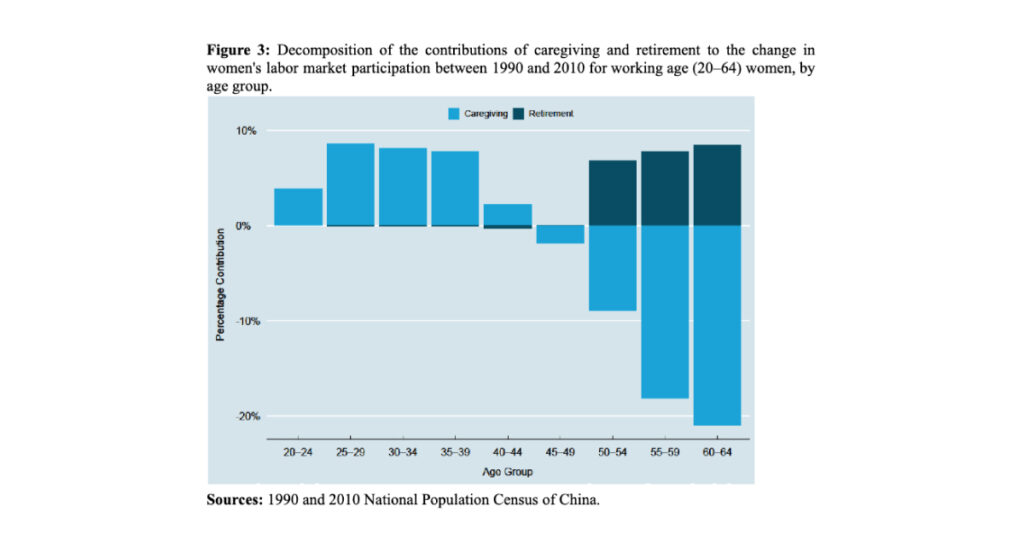

This study does not necessarily contradict previous findings, however. Figure 3 presents the contribution of caregiving and retirement to the change in women’s labor force participation between 1990 and 2010.

Among younger women, the rate of non-participation in the labor force due to caregiving rose, aligning with the explanations of increased work-family conflict and gender discrimination. Compared to 1990, the rise in caregiving rates among younger women in 2010 was offset by a decrease among older age groups. However, this does not imply that women undertake fewer caregiving responsibilities in their older years now than in the past. Rather, women now are more likely to cite retirement as their reason for not participating in the labor force.

Is early statutory retirement age a good thing for women?

The topic of women’s early retirement is hotly debated in China. While many men argue that the system is unfair because men are required to work for more years than women before they can retire, the question remains: is an early statutory retirement age truly beneficial for women?

On the surface, early retirement may seem advantageous, but being able to retire with financial independence is another story: the gender-based retirement system contributes to a gender pension gap, with women receiving fewer pension benefits (Giles et al 2023). An institutionalized policy that requires women to retire earlier than men may further hinder women from advancing to senior positions on the professional ladder.

Within a household, men and women often pool resources, including pensions, savings, housing, and assistance from their children. However, as singlehood and childlessness rates increase, early retirement may put single and childless women in precarious financial situations. Moreover, as the population continues to age, there are growing concerns about the long-term sustainability of the current pension system (Cai, Wang, Shen 2018). The upcoming generation might not receive the same pension benefits as their parents. Consequently, for many people, labor earnings might emerge as a more reliable income source than a pension. Thus, ensuring equal labor rights for women and men at older ages is becoming imperative.

Rising retirement age

Discussion on retirement age should distinguish between effective retirement age and statutory retirement age. Even with a new pension system that includes rural residents, the retirement age holds minimal weight for millions of low-skilled migrant workers, as many will continue working as long as they physically can. The pension disparity between urban hukou holders and their rural counterparts is huge (Giles et al., 2023). Still, a static and gender-based retirement age could place additional strain on these workers. The current retirement system might leave many workers above retirement age, especially a higher proportion of women, vulnerable due to inadequate labor protections, such as accident and injury insurance. This could also make employers hesitant to hire older individuals due to associated risks.

For years, raising the retirement age has been considered a policy strategy to boost the workforce and, more importantly, to address the looming pension deficit. Considering that, after years of economic development, China currently has the most educated and healthiest population in its history (Wang 2023), the country appears well-positioned to enact this policy. However, alongside the widely discussed urban-rural divide, it is important to integrate a gender perspective into ongoing discussions about retirement and pension reform to avoid maintaining or even exacerbating the inequality in middle and later life stages.

References

Cai, Y., Wang, F., & Shen, K. (2018). Fiscal implications of population aging and social sector expenditure in China. Population and Development Review, 811-831.

Feng, K. (2023). Unequal Duties and Unequal Retirement: Decomposing the Women’s Labor Force Decline in Postreform China. Demography, 60(5), 1309-1333.

Giles, J., Lei, X., Wang, G., Wang, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2023). One country, two systems: evidence on retirement patterns in China. Journal of pension economics & finance, 22(2), 188-210.

Ji, Y., Wu, X., Sun, S., & He, G. (2017). Unequal care, unequal work: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of gender inequality in post-reform urban China. Sex Roles, 77, 765-778.

Wang, F, 2023, Should or should not China be afraid of population decline?, Neodemos

Source Figure 1 – Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE)