U.S. teen mothers’ smoking risk in adulthood

After following about one thousand U.S. teen mothers into young adulthood, Stefanie Mollborn, Juhee Woo, and Richard Rogers, found that these women are 2.5 times as likely as other women to smoke as young adults, with the highest risk among Whites.

Their disadvantaged social backgrounds and compromised socioeconomic attainment largely explain their elevated smoking risk.

Teen childbearing and cigarette smoking are two major global public health issues confronting young people, but their interrelationship is unclear. Addressing this relationship is the focus of our recent article (Mollborn, Woo, and Rogers 2018).

Teen mothers’ risk of daily smoking in adolescence and adulthood

We tracked teen mothers’ smoking across the transition to adulthood. Restricted data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Harris et al. 2009) allowed us to follow approximately 1,000 teen mothers in a nationally representative sample from before they got pregnant and when they were middle or high school students in the mid 1990s, to several years after the pregnancy at ages 24-32 in 2008. We compared them to about 3,000 women who had first given birth after their teens and to about 3,500 women who had not given birth.

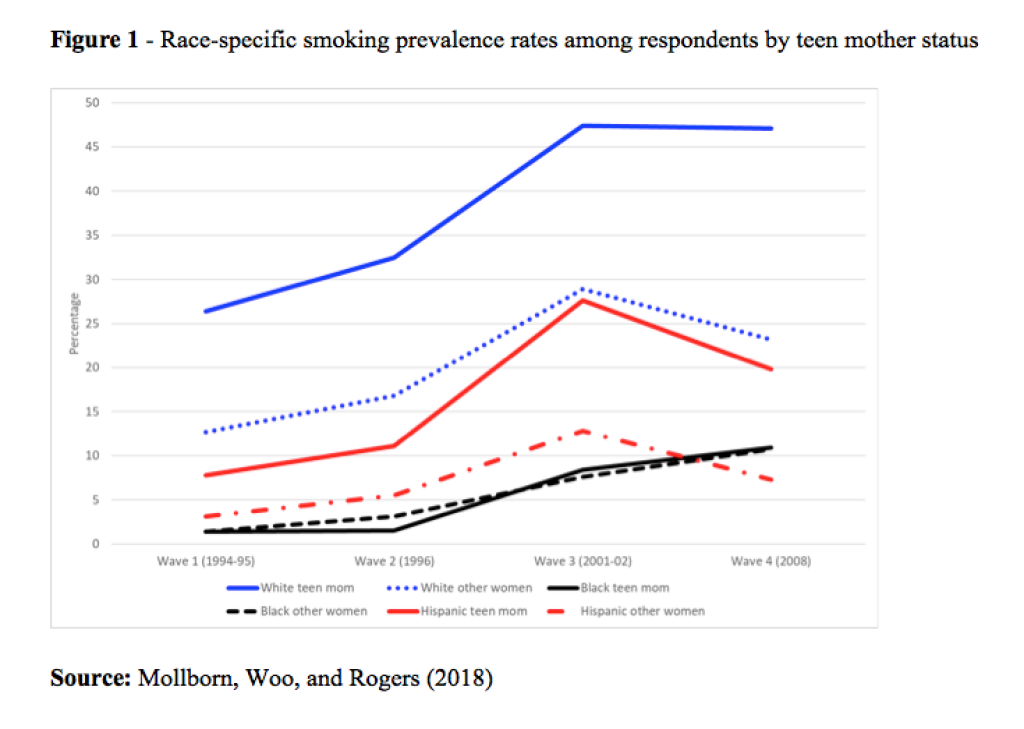

We found that teen mothers were at elevated risk of daily smoking even before they became pregnant (Figure 1). This finding is unsurprising given the high levels of social disadvantage typically experienced by teen mothers (Kane et al. 2013) and given that socially disadvantaged populations have higher rates of smoking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014). After the birth, teen mothers’ smoking rates continued to increase, resulting in a wider smoking disparity in young adulthood compared to adolescence. At ages 24-32, teen mothers were 2.5 times as likely to be daily smokers as were other young women. Although we could not measure teen mothers’ smoking after that point, early smoking often leads to higher rates of smoking in later adulthood.

Which teen mothers are at risk of smoking

Figure 1 reveals that there are large racial and ethnic differences in teen mothers’ smoking risk. White teen mothers had by far the greatest smoking risk, with about one quarter smoking daily before the pregnancy, rising to nearly half at ages 18-26 and 24-32. Even White women who were not teen mothers had higher daily smoking risk at all time points than any group of Latina or African American women, a finding that reflects previous research (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014). Latina teen mothers’ smoking risk began low before pregnancy, at under 10% smoking daily, peaked at about 25% at ages 18-26, and decreased to around 20% at ages 24-32. This risk was significantly higher than the risk of daily smoking for Latina non-teen mothers. In contrast, African American women’s smoking risk began very low and remained fairly low, at about 10% smoking daily. The risk of daily smoking was not higher for African American teen mothers compared to other African American women.

Why teen mothers are at risk of smoking

The selection of socially disadvantaged young women into teen childbearing partially explained their higher risk of smoking in young adulthood. We accounted for risk factors that predated the teen pregnancy, including demographic characteristics, academic achievement, risky behaviors, and preexisting daily smoking. After taking these preexisting factors into account, teen mothers were 50% more likely than other young women to smoke daily in young adulthood.

We then sought to identify pathways through which becoming a mother as a teenager leads to elevated smoking risk in young adulthood. We found two such pathways: teen mothers’ lower educational attainment and their household income in young adulthood. Teen childbearing decreases subsequent educational attainment and income, which are tied to smoking risk. This socioeconomic attainment pathway, together with preexisting risk factors among teen mothers, explained why White and Latina teen mothers were more likely to be daily smokers in adulthood.

What can be done?

Teen mothers’ lower socioeconomic status and riskier behaviors contribute to social disadvantages later in their lives. And their much higher risk of smoking may result in further disadvantage. Smoking during pregnancy or after childbirth can compromise the health of mother and child, increase their risk of disease and death, and further exacerbate teen mothers’ social disadvantage. This is one pathway through which socioeconomic and health disadvantage may accumulate among teen mothers and contribute to the intergenerational transmission of poor health. Social disadvantage predicts becoming a teen mother, which typically results in lower socioeconomic attainment. This in turn is associated with an increased risk of smoking, which elevates risks for preterm birth, low birth weight, and infant and child morbidity and mortality. Unhealthy infants and children may require expensive healthcare and may experience delayed development that further stresses the mother and slows her socioeconomic progress, perpetuating a vicious cycle of intergenerational inequalities in health and socioeconomic attainment.

We contend that a good way to interrupt this intergenerational cycle is to concurrently reduce low socioeconomic status and teen childbearing. For example, policies that improve educational quality and access to contraception are promising for also reducing teen mothers’ later cigarette smoking. Reducing these risks could simultaneously improve the health and social position of particularly vulnerable subpopulations: teen mothers and young children. Investments in teen mothers and infants could pay long-term future dividends because of the intergenerational implications of improving young families’ health and socioeconomic status.

References

Harris, K.M., Florey, F., Tabor, J., Bearman, P.S., Jones, J., and Udry, J.R. (2009). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design.

Kane, J.B., Morgan, S.P., Harris, K.M., and Guilkey, D.K. (2013). The educational consequences of teen childbearing. Demography 50(6): 2129-2150. doi:10.1007/s13524-013-0238-9.

Mollborn, S., Woo, J., and Rogers, R.G. (2018). A longitudinal exploration of US teen childbearing and smoking risk. Demographic Research 38(24): 619-650. DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.24 (click here)

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.