The effect of migration on the fertility of Chinese women in the USA

In the years between 1975 and 2005, migrants from China to the US were more likely to have a second and third birth than non-migrant Chinese. Wanli Nie and Pau Baizan argue that both “emancipation” (i.e., liberation from the constraints of the Chinese restrictive family policy of the time) and adaptation to the new context played a role. In all cases, the fertility enhancing effect of migration decreased for younger birth cohorts.

Those who migrate from high- to low-fertility countries typically reduce their fertility over time, as was the case, for instance, among Indians, Bangladeshis and Pakistanis who moved to the UK (Dubuc 2012). But what happens in different scenarios, when people move from low to (relatively) high fertility countries?

In a recent paper, we focused on the Chinese birth cohorts of 1960‒1990, and among them, on those who migrated to the United States. We measured their fertility between 1975 and 2005 tapping several data sources: the 2000 US census, the 2005 American Community Survey, the 2000 Chinese census, and the 2005 Chinese 1 percent Population Survey, with data for the first three sources taken from the IPUMS dataset (Nie and Baizan, 2021).

In particular, we tested four hypotheses on the influence of migration on fertility:

• Emancipation: “the fertility of Chinese women, which was kept low by Chinese fertility policies, should bounce back after emigration to the United States” (Hwang and Saenz 1997:50).

• Adaptation: immigrants progressively converge towards the fertility standard of the hosting country.

• Disruption: migration breaks the natural process of family formation and drastically reduces fertility.

• Selection: those who migrate differ from those who do not in several respects. Among other things, they prefer lower fertility.

We analyzed three groups of Chinese:

1) those who remained in China (non-migrants),

2) those who migrated to the United States after their 15th birthday (first generation migrants) and

3) those who migrated to the United States before their 15th birthday (1.5-generation migrants).

To better understand our results, keep in mind that in the period under consideration, between 1975 and 2005, three phases of family policy in China can be distinguished:

1) the “Later, Longer, Fewer” policy of 1975-1979, which imposed later marriage, a longer interval between births, and a maximum of two or three children per couple (in urban and rural areas, respectively),

2) the first and strictest phase of the one-child policy, between 1980 and 1985 (although implementation was somewhat uneven, and the timing of relaxation varied slightly across provinces), and

3) the progressive relaxation of the one-child policy, between 1985 and 2005.

A noticeable, but declining, emancipation effect

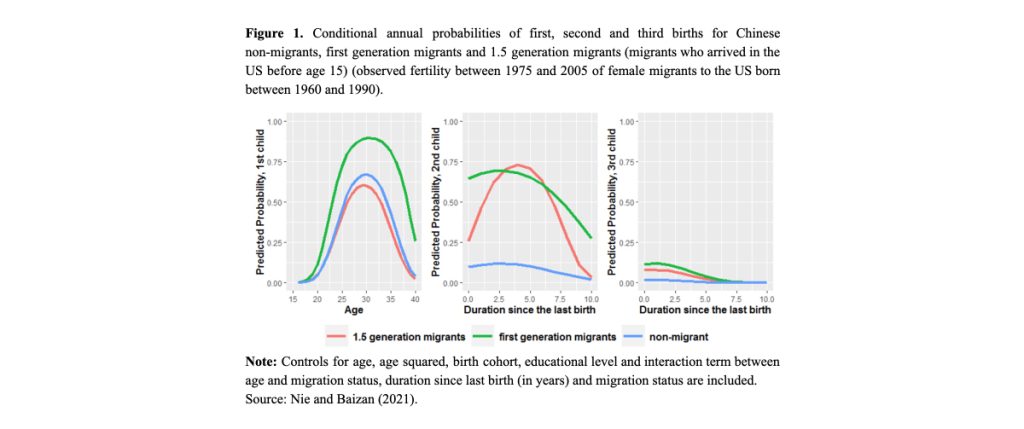

Not surprisingly, Chinese migrants to the US had a markedly higher fertility than non-migrants, especially in the case of the second child (Figure 1), the main target of China’s one-child policy, under which second births were allowed only in special cases (e.g. for ethnic minorities, or if the first born was a female, but only in rural areas).

The higher fertility of Chinese migrants was therefore largely due to an “emancipation” effect: the constraints of China’s strict family policy were no longer valid for them. Surprisingly however, Chinese migrants rarely went for a third child, which suggests that their preferred family size was already relatively low, not far from two (Gietel-Basten 2019).

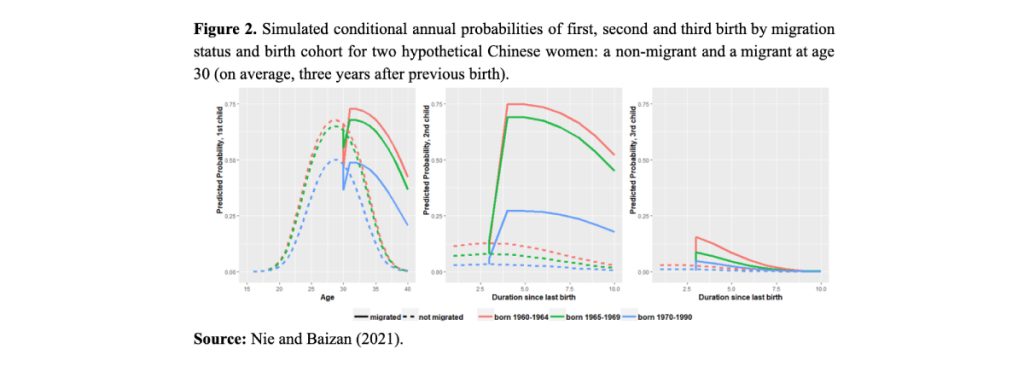

Probably our most important finding is that this emancipation effect declined across birth cohorts, especially for second births (Figure 2). While the constraints of China’s one-child policy were slowly relaxed, starting in mid-1980s, the ideal number of children likely declined for Chinese couples due to a complex set of circumstances, such as rapid economic development, higher female employment, increasing urbanization and rising childcare costs.

Adaptation? Not really…

Our results also shed light on the adaptation hypothesis, which argues that migrants’ fertility should gradually converge towards that of natives (Milewski 2010). In the China-US migration context, if the adaptation hypothesis held, one should observe that migration’s positive effect on second births increases across birth cohorts as the gap between China and US fertility levels widens (China’s fertility was higher than that of the US before the 1990s, but later fell below it). In our case, this did not happen. However, Chinese migrants seem to have “adapted” to a cultural context with less (and possibly no) son preference. Compared with non-migrants, Chinese migrants are less likely to have an extra child if they only have daughters.

Migration, education and fertility

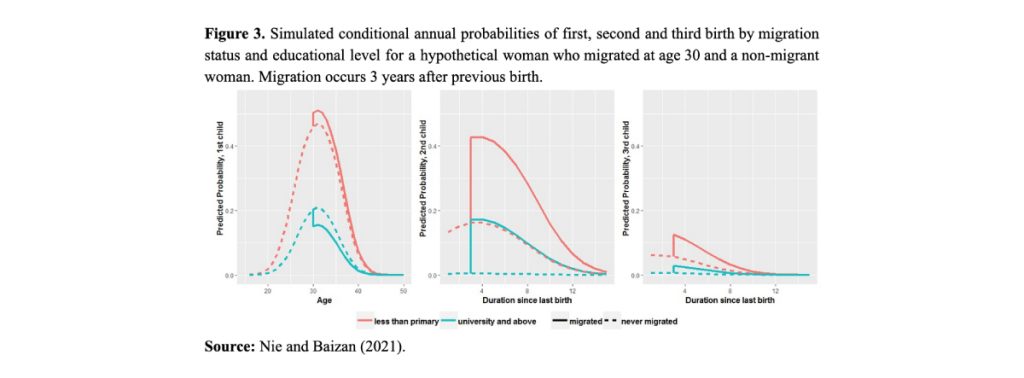

Migration to the USA had a positive effect on second and third births for women at all levels of education. For reasons of clarity, Figure 3 shows only two extreme cases: very high (university level) and very low (less than primary) education. Note, however, that highly educated migrant women are more likely to postpone their first birth or remain childless: at age 40, childlessness among them is much higher (25%) than among well-educated non-migrants (6%).

Conclusion

In short, while migration has had an overall positive effect on the fertility of Chinese migrants to the US, this is less true for younger and highly educated migrants. This can probably be explained by the selection hypothesis: migrants (in general, not just in this case) tend to have lower fertility because they have other life goals, such as pursuing a career and having less constraining family ties.

As fertility decline continues in several Asian countries (Jdanov and Sobotka 2019) while remaining close to replacement levels in some western countries (at least, until recently), more examples of migration from low- to high(er)-fertility settings may be observed in the future. We predict that this will result in increased fertility among migrants. However, this effect is likely to be limited in extent and short-lived.

References

Dubuc, S. 2012. Immigration to the UK from High-fertility Countries: Intergenerational Adaptation and Fertility Convergence. Population and Development Review 38(2): 353–68.

Gietel-Basten, S. 2019. The Population Problem in Pacific Asia. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hwang, S.-S., and R. Saenz. 1997. “Fertility of Chinese Immigrants in the U.S.: Testing a Fertility Emancipation Hypothesis.” Journal of Marriage and Family 59(1): 50–61.

Jdanov, D., and T. Sobotka. 2019. Human Fertility Collection. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany) and Vienna Institute of Demography (Austria).

Milewski, N. 2010. Fertility of Immigrants: A Two-generational Approach in Germany in Demographic Research Monographs. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Nie, W., & Baizan, P. (2021). Does Emancipation Matter? Fertility of Chinese International Migrants to the United States and Non-migrants during China’s One-child Policy Period. International Migration Review. Online first