Return migrants’ fertility is likely to differ from that of nonmigrants and migrants due to migration experiences, norms, adaptation, and socioeconomic factors, but knowledge of their fertility behavior is limited. A study of return migrants to overseas France was conducted to shed light on this question. The analyses carried out by Marine Haddad and Ariane Pailhé reveal differences in fertility timing and levels, with return migrants having more children than migrants, but fewer than nonmigrants.

Return migration to one’s country of origin accounts for approximately a quarter of international migration flows (Azose and Raftery 2019). We know more and more about this phenomenon, but mostly from an economic perspective, for instance in terms of employment (Bijwaard et al. 2014; King 2015). Information on the family dimension of returns, including fertility, is lacking, however. Many studies document migrants’ fertility behaviors while they are away, but not after they return (Kulu et al. 2017; Behrman and Weitzman 2022). Yet, return migrants’ profiles and trajectories are different from those of both migrants who remain at destination and nonmigrants (Lindström and Giorguli Saucedo 2007).

Why should return migrants’ fertility be specific?

With their experience of different norms, practices and economic contexts, return migrants differ from nonmigrants. They also face the challenges of relocating and settling in new environments, a disruption to their life cycle that may temporarily reduce their fertility. Return migrants may also have socioeconomic backgrounds and positions, motivational traits and fertility preferences that predispose them to have fewer children than nonmigrants. Besides, the multiple migrations of return migrants expose them to additional disruptive events which might further delay childbearing.

Migrants who return home tend to stay only temporarily at destination or remain for shorter periods than those who stay at destination. This may signal stronger social ties with people at origin or specific migration experiences, whether “failure” or “success”. Returnees might have fewer incentives to adapt their behaviors to the host country norms, which may well result in their fertility lying somewhere between that of nonmigrants and that of migrants. However, only a handful of studies actually compare return migrants to nonmigrants and migrants.

To fill this gap, in a recent study (Haddad and Pailhé 2024), we focused on four of the five French DOMs (départements d’outre-mer), Martinique, Guadeloupe, French Guiana, and Réunion Island, all former colonies which are now fully integrated into the French political system. We merged two representative biographical surveys conducted by INED:

a) Trajectories and Origins conducted in 2009 in metropolitan France, and

b) Migration, Family and Ageing conducted in 2010 the DOMs.

We compared the first-birth transition rates and completed fertility of three groups:

1) nonmigrants (women who never left their region of origin),

2) migrants (women continuing to reside in the destination country), and

3) return migrants (women who returned to their home region after migration).

Migration and family in the French overseas departments

Emigration and return migration are frequent in the DOMs, and most emigrants choose metropolitan France (mainland France and Corsica) for their destination. According to the 2014 French census, more than one in four individuals born in the French Caribbean resided in metropolitan France, compared with one in six for the French Guianese and one in seven for the Réunionese. The Migration, Family and Ageing survey found that nearly one third of natives currently living in these French overseas regions in 2010 had spent at least six months outside their DOM of birth. Given the political continuity and free movement between the DOMs and metropolitan France, DOM-mainland migration is defined as internal migration. However, given the thousands of kilometers that separate the DOMs and metropolitan France, their substantial differences in socioeconomic development and the racial hierarchies that characterize their populations, DOM-mainland migration is rather similar to international migration.

In the final decades of the twentieth century, the fertility gap between mainland and overseas France narrowed. DOM fertility rates are now similar to those of metropolitan France (2.0 children per woman) in Martinique (2.0) and Guadeloupe (2.1), slightly higher in Réunion Island (2.4) and significantly higher in French Guiana (3.7). Disparities in age at first birth are larger, however, with women from the DOMs still experiencing first births at early ages.

Return migrants’ fertility: lower than nonmigrants but higher than settled migrants

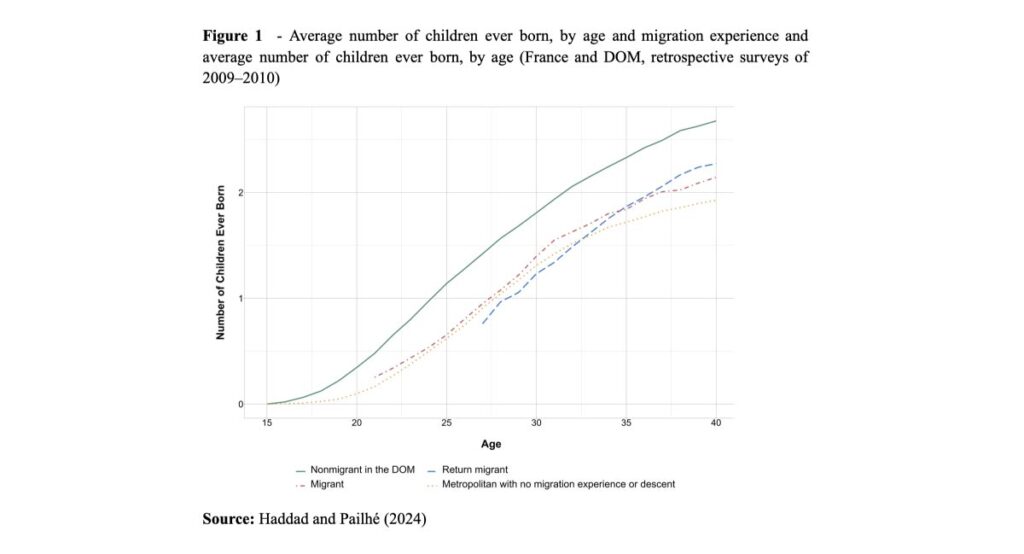

Return migrants initiate motherhood at the same age (26 years) as migrants living in metropolitan France and later than nonmigrants residing in the DOMs (24 years). They have more children by age 40 (2.4) than permanent migrants (2.1) but fewer than nonmigrants (2.7). These differences build over migrants’ life course (Figure 1). At any age, return migrants have fewer children than nonmigrants. Until age 30, their fertility levels are also lower than those of migrants, but they gradually catch up, and, by around age 35, eventually surpass them.

Compared to French women who have always lived in mainland France, migrants’ cumulative fertility is slightly higher at all ages, whereas return migrants initially lag behind, but later catch up.

When controlling for socioeconomic status and partnership history, no significant difference is observed between the first-birth transition rates of nonmigrants and return migrants: disruption appears to be a relevant factor for those who emigrate, but less consequential upon their return. However, migration intentions matter: prospective migrants have lower first-birth rates than nonmigrants in the DOMs, probably because they anticipate future disruption before migrating. Migration and return migration are also related to union formation and childbearing. Women planning to emigrate tend to postpone couple formation until after their migration, delaying their first childbirth. Among return migrants, union formation correlates more weakly with childbearing.

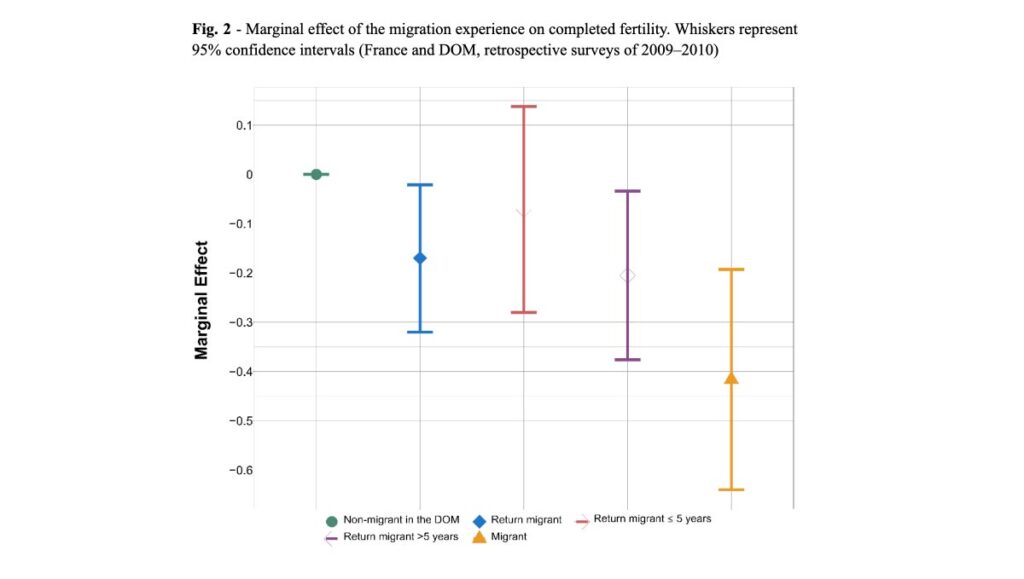

Differences across migrants, return migrants, and nonmigrants are larger for completed fertility than for first-birth timing. With controls for socioeconomic background and partnership history, return migrants display lower levels of completed fertility than nonmigrants, especially among longer-staying return migrants (Figure 2). Migrants residing in metropolitan France have, on average, 0.42 fewer children than nonmigrants in the DOMs. Return migrants also exhibit slightly lower levels of completed fertility than nonmigrants (–0.17, on average); this effect is driven primarily by those returning after five or more years who have significantly fewer children than nonmigrants. Although confidence intervals partially overlap, return migrants have more children than migrants at destination.

Conclusion

On average, completed fertility levels are lower among return migrants than nonmigrants but slightly higher among return migrants than migrants. Some of these differences can be attributed to selection into migration and return, although significant gaps persist among women with similar socioeconomic characteristics.

References

Azose J.J., Raftery A.E. 2019. Estimation of emigration, return migration, and transit migration between all pairs of countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(1): 116–122.

Behrman J.A, Weitzman A. 2022. Point of Reference: A Multisited Exploration of African Migration and Fertility in France. International Migration Review 56(3): 911–940.

Bijwaard G., Schluter C., Wahba J. 2014. The impact of labour market dynamics on the return‐migration of immigrants. Review of Economics and Statistics 96(3): 483–494

Haddad M, Pailhé A. 2024. Return Migration and Fertility: French Overseas Emigrants, Returnees, and Nonmigrants at Origin and Destination. Demography 61(2): 569-593. doi: 10.1215/00703370-11235052. PMID: 38506316.

King R. 2015. Return Migration and Regional Economic Development: An Overview. Return migration and regional economic problems, 1–37

Kulu H., Hannemann T., Pailhé A., Neels K., Krapf S., González-Ferrer A., Andersson G. 2017. Fertility by Birth Order among the Descendants of Immigrants in Selected European Countries. Population and Development Review 31–60.

Lindström D.P., Giorguli Saucedo S. 2007. The Interrelationship between Fertility, Family Maintenance, and Mexico-U.S. Migration. Demographic Research 17: 821–58.