Family policies such as parental leave schemes increasingly support the work-family balance. Although labour force participation has increased in recent decades among mothers in majority populations, maternal employment levels and uptake of family policies remain low in migrant populations across Europe, and the two are related: precarious employment trajectories may limit access to parental leave schemes, as in the case of Belgium, for instance. Using longitudinal data from Belgian social security registers, we look into the association between migration background and leave uptake for 10,976 mothers who had their first child between 2004 and 2010.

Parental leave legislation in Belgium

In Belgium, parental leave is an individual entitlement and the right is not transferable from one parent to the other. To be entitled, an employee needs to have worked for the current employer for 12 out of 15 months prior to the application, and to have a child younger than 12. Working hours can be reduced in three ways: i) a 100% reduction for a maximum of three months, ii) a 50% reduction for up to six months, or iii) a 20% reduction limited to 15 months. Parents on parental leave receive a flat-rate benefit, which was 727 euro per month for full-time leave in 2010. Given that i) parental leave can be used until the child is 12 years old, ii) periods can be split up, iii) varying degrees of work-time reduction are possible and iv) the 20% work-time reduction is the most popular, the Belgian parental leave system is relatively flexible from a European perspective. However, the rate of parental leave uptake in Belgium is low, with only 7% of all eligible parents taking parental leave in 2007. Moreover, parental leave uptake is strongly gendered: 20% of employed mothers with a child under age one take leave, while the proportion of employed fathers taking leave is close to zero.

Migrant populations in Belgium

Belgium has a substantial and diverse migrant population. As a result of active recruitment of migrant workers from Southern Europe, Turkey and Morocco after the Second World War and post-colonial migration from Congo, Belgium is an old immigration country. In recent decades, the gradual enlargement of the European Union and the free movement of people within its borders have given rise to immigration streams from Eastern Europe. In addition to migration from Southern and Eastern Europe, a large proportion of European migrants in Belgium originate from neighbouring countries, facilitated by common languages. Regarding non-European immigration, migration flows of asylum seekers have further contributed to Belgium’s ethnic diversity. Migrants in Belgium are characterized by relatively low employment and income levels and they are generally overrepresented in unstable labour market positions.

Migrant-native differentials in leave uptake

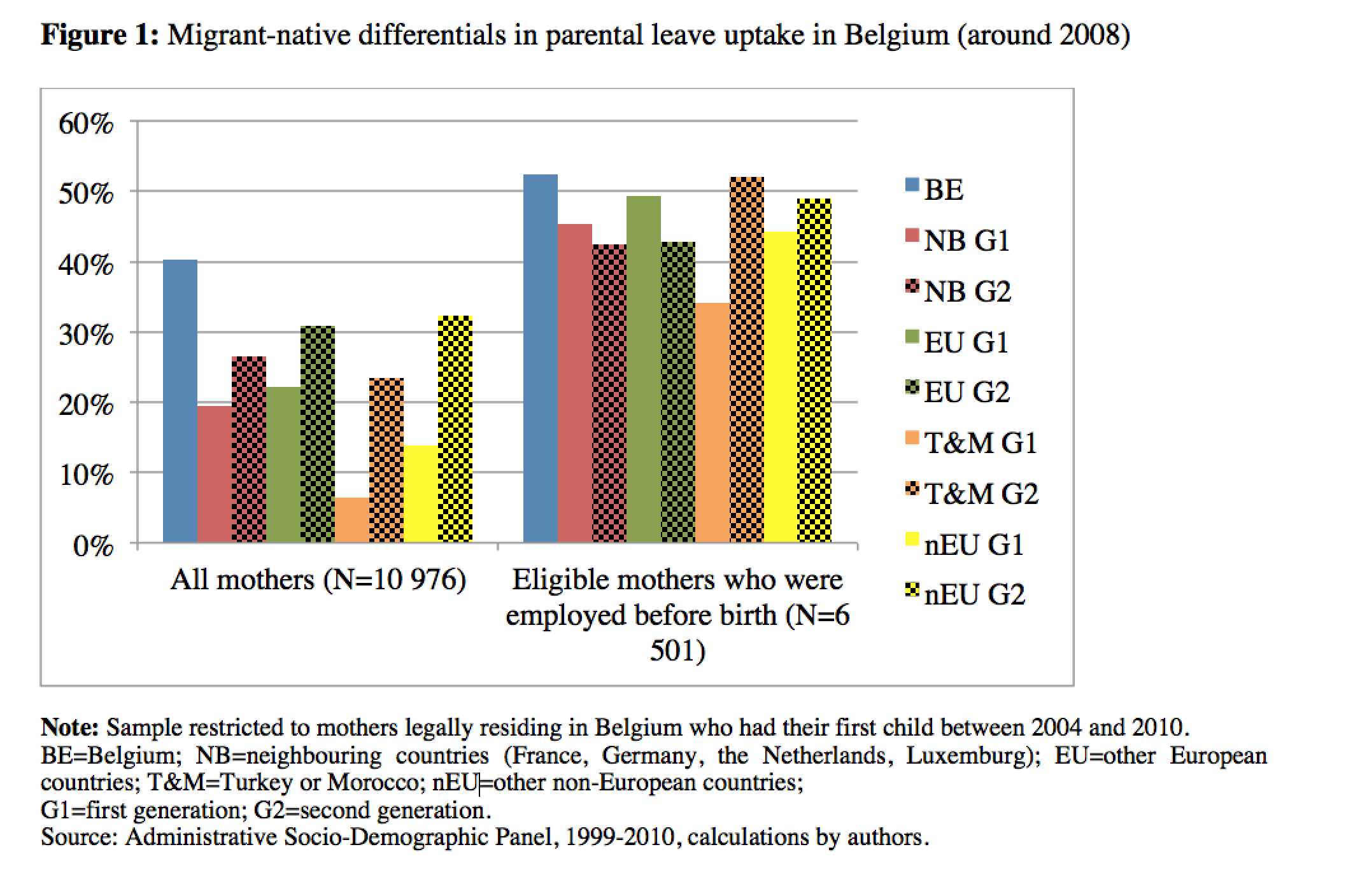

The results of our study (Kil, Wood and Neels 2017) indicate that uptake of parental leave is lower among mothers of migrant origin than among natives. Whereas 40% of native mothers took parental leave following the transition to parenthood, this proportion is lower among first-generation migrants originating from i) neighbouring countries (19%), ii) other European countries (22%), iii) Turkey or Morocco (6%) and iv) other non-European countries, respectively (13%; Figure 1). Although the proportion of mothers taking leave is considerably higher among second-generation migrants, uptake levels do not match those of native women.

However, when considering only the 6501 mothers who were working when they became a parent and who at some point in the observation period were eligible for parental leave, differences become considerably smaller. Differences in uptake rates between women of Belgian origin (52%) and first- and second-generation women originating from neighbouring countries (45 and 42%), other European countries (49 and 43%), and other non-European countries (44 and 49%) and second-generation women of Turkish and Moroccan origin (51%) are very small in this subset of women. The uptake rates of first-generation women of Turkish and Moroccan origin, however, continue to be relatively low (34%). Additional multivariate analysis shows that after controlling for pre-birth employment regime, number of jobs, salary and sector of employment, migrant-native differences further diminish and are no longer significant. In sum, the differential socio-economic position before parenthood and eligibility requirements largely explain migrant-native differences in leave uptake. Because migrant women are overrepresented in unemployment/inactivity and unstable employment, they fail to meet the eligibility requirements.

Implications

This study indicates that in Belgium – a country where eligibility is connected to labour force attachment – parental leave reinforces labour market disadvantages by providing work-family reconciliation to those already established in the labour force. As Belgium is also characterized by low employment levels among migrants, this implies that migrants in particular are underrepresented among the beneficiaries of subsidized leave schemes. If policy makers aim to enhance the inclusiveness and effectivity of family policy, the design features of parental leave entitlements in relation to labour market disadvantages need to be reconsidered.

References

Kil T., Wood J., Neels K. (2017). Parental leave uptake among migrant and native mothers: Can precarious employment trajectories account for the difference? Ethnicities (Online First) http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1468796817715292