Future fears: societal pessimism and fertility choices

Katya Ivanova and Nicoletta Balbo examine the link between societal pessimism and fertility decisions. Using prospective data from the Dutch LISS panel, the authors illustrate that broader concerns about the future of the next generation can deter young adults from entering parenthood.

“I do not dare to bring a child into this world” [Op deze wereld durf ik geen kind te zetten] stated the title of a newspaper article in the Netherlands, at the end of 2021. This sentiment is not an isolated occurrence: titles such as “Given the state of the world, is it irresponsible to have kids”, “The rise and rise of the birth strike”, and “Should I have children? Weighing parenthood amid the climate crisis” have been appearing regularly in news outlets over the past decade. The question of why people choose (not) to have children has never been merely academic. Currently, about half of the world’s population lives in countries with sub-replacement fertility levels. The undeniable impact of declining fertility rates on the sustainability of (Western) welfare states has made this issue a critical area for policymaking. Numerous policy analyses have sought to identify effective strategies for encouraging people to have more children (see Sobotka, Matysiak & Brzozowska 2020). Yet, fertility rates continue to fall, even in countries like Finland and Norway, which have made significant, sustained investments in creating conditions that facilitate the combination of work and family life equitably for both partners. Why?

Societal pessimism and fertility

In a recently published study (Ivanova & Balbo 2024), we pointed to one potential culprit: societal pessimism, or the general feeling that things are not moving in the right direction in society at large. Over recent decades, fear and discontent have increasingly become prominent traits of Western societies. Previous efforts to understand the consequences of societal pessimism have concentrated on its potential to affect attitudes toward out-group members such as migrants, as well as political preferences and voting behaviors, particularly in support of populist parties. We argue that societal pessimism can also influence demographic behaviors, such as fertility. People generally expect their children to fare better than, or at least as well as, themselves. Therefore, especially in contexts where voluntary childlessness is becoming more socially acceptable (for example, the Netherlands; Noordhuizen, de Graaf & Sieben 2010), the perceived conditions that the next generation may face – conditions that individuals feel they cannot directly improve – might significantly shape fertility decisions.

Societal pessimism or pessimism about own future?

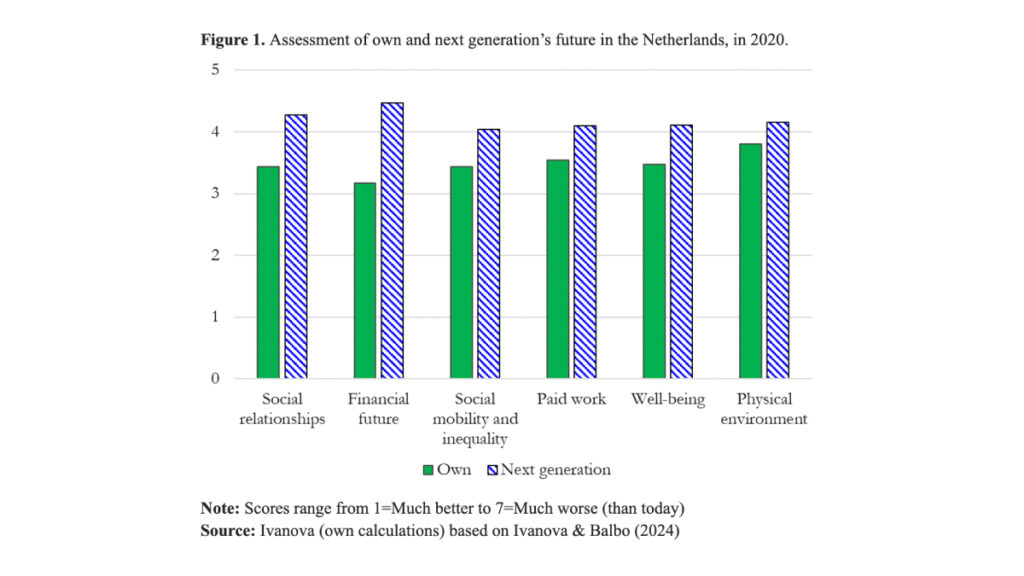

To determine whether societal pessimism influences fertility behaviors, we first need to understand if people indeed differentiate between their personal futures and the broader future of the next generation. We utilized the Dutch Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS), a panel created in 2010. When joining the panel, all respondents evaluate various aspects of life (e.g., social relationships, financial prospects, and overall well-being) and, with a 7-point scale, they state whether, in their opinion, the future of the next generation will be significantly better (=1) or worse (=7) than today in each of those areas.

To ascertain by how much people distinguish between the future of the next generation and their own, we carried out additional data collection in 2020. At that point, respondents were asked the original questions plus the same questions but with an explicit focus on their own future. We found that our respondents were more optimistic about their own future than about that of others, specifically the next generation (Figure 1). This aligns with empirical research showing that individuals tend to be more optimistic about their own chances of success and happiness than those of generalized others, a phenomenon known as the ‘optimistic bias’, ‘unrealistic optimism’, and the ‘optimism gap’ (Whitman 1998).

Does societal pessimism matter for the transition to parenthood?

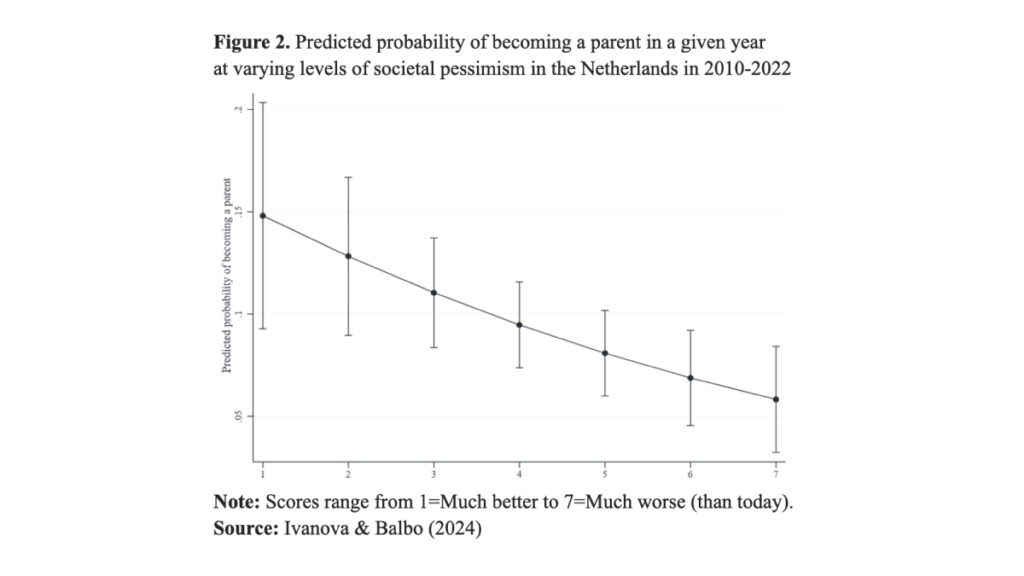

For our study, we focused on adults who were not parents at entry into the LISS panel (when they filled out the societal pessimism measure) but were still relatively young (less than 40 and 45 years old, respectively, for women and men). We “followed” these individuals from their entry into the panel (as early as 2010) until they became parents, dropped out, reached the age of 45 for women and 50 for men, or until the end of observation (2022). Figure 2 displays the predicted probability of becoming a parent, across self-reported societal pessimism scores. What we found is that those who scored higher on societal pessimism were less likely to have a child, even accounting for the level of depression and satisfaction with own income (at the time when they entered LISS).

Why does it matter?

The newspaper headlines mentioned at the start of this article suggest that young adults actively consider the general state of the world when deciding whether to have children. However, these narratives are often captured at a single moment in time. This limitation prevents us from confirming whether these sentiments actually influence behavior. Additionally, it provides detractors with an opportunity to dismiss these narratives, arguing that intentions change as people age. Our findings show that in a society where opting not to have children is increasingly seen as acceptable, the transition to parenthood is indeed influenced by the perception of the world those children would live in.

We do not imply that the imagined future of the next generation is the sole driver of declining fertility rates across the Global North. Undoubtedly, improving the current living conditions of young adults is paramount if countries are interested in reversing this trend. At the same time, it is essential to recognize that even when individuals feel secure about their own future, they might decide to forego parenthood in a world characterized by climate change, increasing inequality, and social polarization.

References

Ivanova, K. & Balbo, N. (2024). Societal pessimism and the transition to parenthood: A future too bleak to have children? Population and Development Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12620

Noordhuizen, S., de Graaf, P., & Sieben, I. (2010). The public acceptance of voluntary childlessness in the Netherlands: From 20 to 90 per cent in 30 years. Social Indicators Research, 99, 163-181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9574-y

Sobotka, T., Matysiak, A., & Brzozowska, Z. (2020). Policy responses to low fertility: How effective are they? (Working Paper No. 1). UNFPA, Technical Division, Population & Development Branch.

Whitman, D. (1998). The optimism gap: The I’m OK-They’re Not syndrome and the myth of American decline (1st ed.). Walker & Co.