Fertility in the time of economic crisis

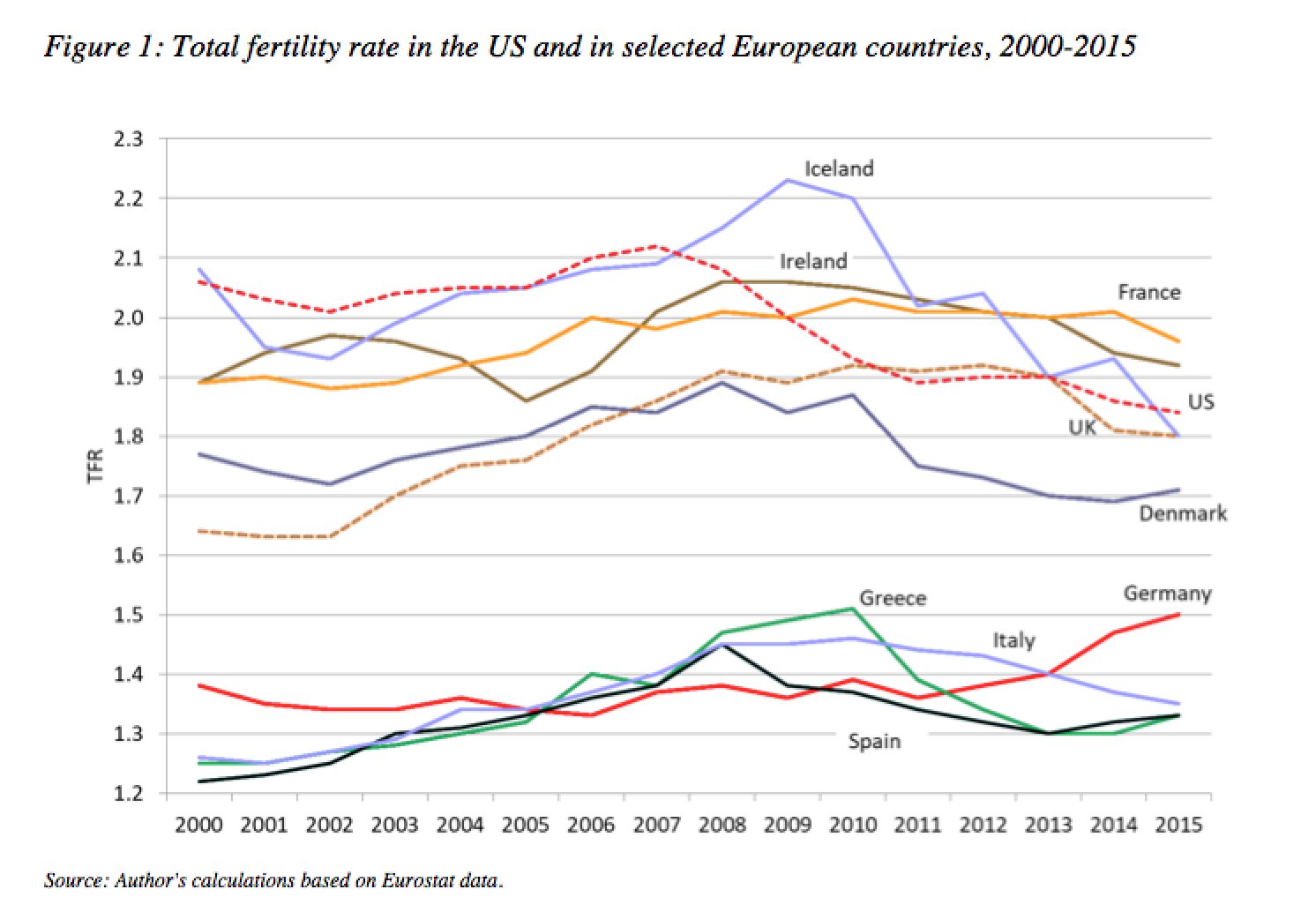

When uncertain about the stability of their present or future earnings or jobs, individuals postpone life-changing decisions. Scientific research confirms conventional wisdom and shows that the Great Recession that started in 2008 had a paralyzing effect on childbearing in most western economies. As illustrated in Figure 1, after a period of growing fertility at the beginning of the 21st century, the US and most countries in Europe registered a sudden fertility decline. Researchers tend to agree that the drop is largely due to the global economic downturn that violently hit those same countries (Sobotka et al. 2011, Pison 2011, Goldstein et al. 2013, Schneider 2015).

Fertility drops when the economy suffers

In developed societies, fertility tends to move in the same direction as the economy: periods of economic decline are characterized by downturns in fertility, followed by more prosperous periods when fertility recovers. The impact of the business cycle on fertility is usually temporary, while persistent demographic trends tend to arise from cultural or technological revolutions. In fact, most 20th century recessions occurred in a context of long-term fertility decline, which was simply accelerated by economic crises. The Great Recession hit western countries after decades of stagnant fertility at exceptionally low historical levels. Thus, even though the short-term effects of the Great Recession might seem mild and temporary, their long-term consequences may be substantial and persistent.

Beyond traditional indicators

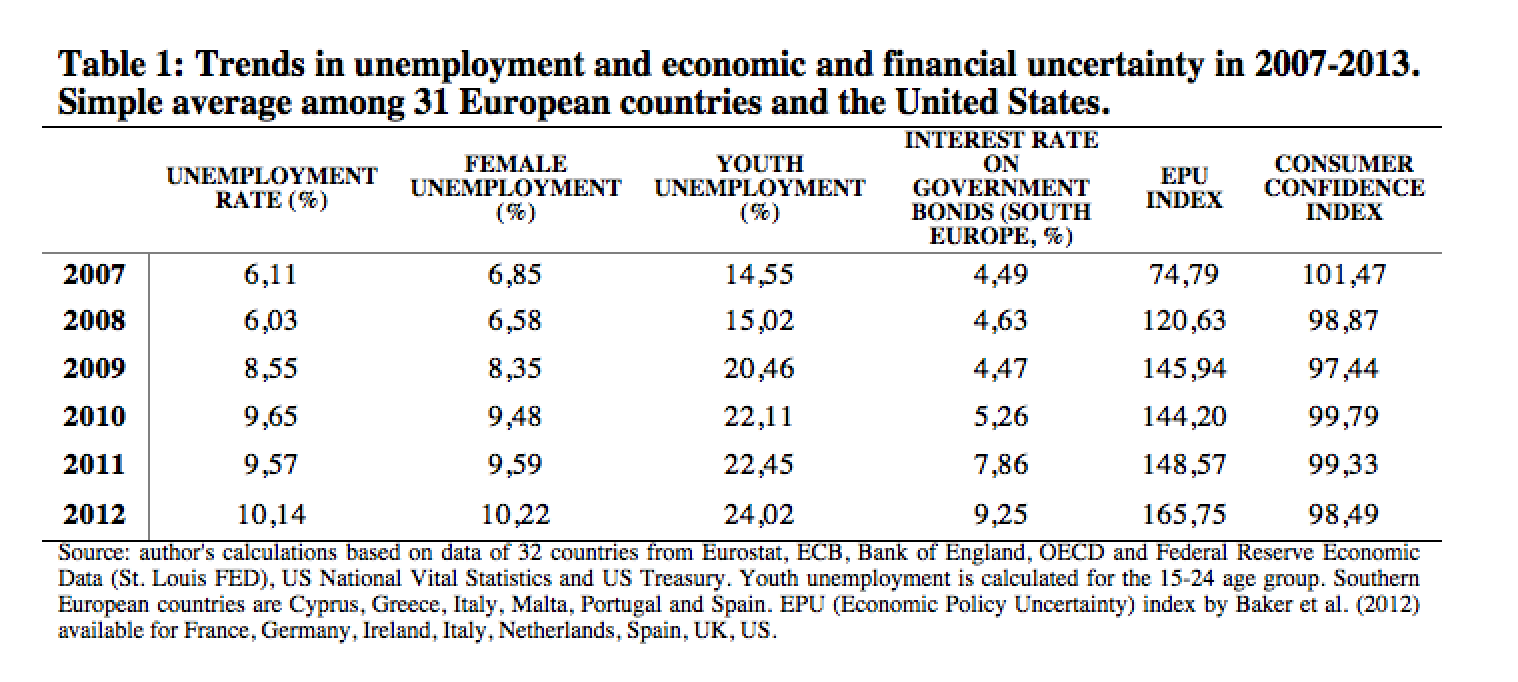

The recent recession has been the longest and most powerful economic shock that advanced economies have faced since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The crisis began in the United States with the bursting of the housing market subprime mortgages bubble, and very soon escalated into a deep recession on both sides of the Atlantic. Table 1 shows the trends of both financial and macroeconomic indicators of the crisis in Europe and the US in the period 2007-2012. After 2008, total unemployment and female unemployment almost doubled and youth unemployment increased by two-thirds. As public debts accumulated, the cost of that indebtedness grew substantially in countries traditionally characterized by large government debts: in southern European countries, as reported in Table 1, the interest rate on sovereign debt doubled between 2008 and 2012. Finally, together with these tangible indicators of the crisis, less visible measures of economic and financial uncertainty also deteriorated during the recession: the future orientation of economic and social policies became less predictable, as shown by the rise in the Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) Index and the drop of the consumer confidence index.

Uncertainty drives down births as much as unemployment

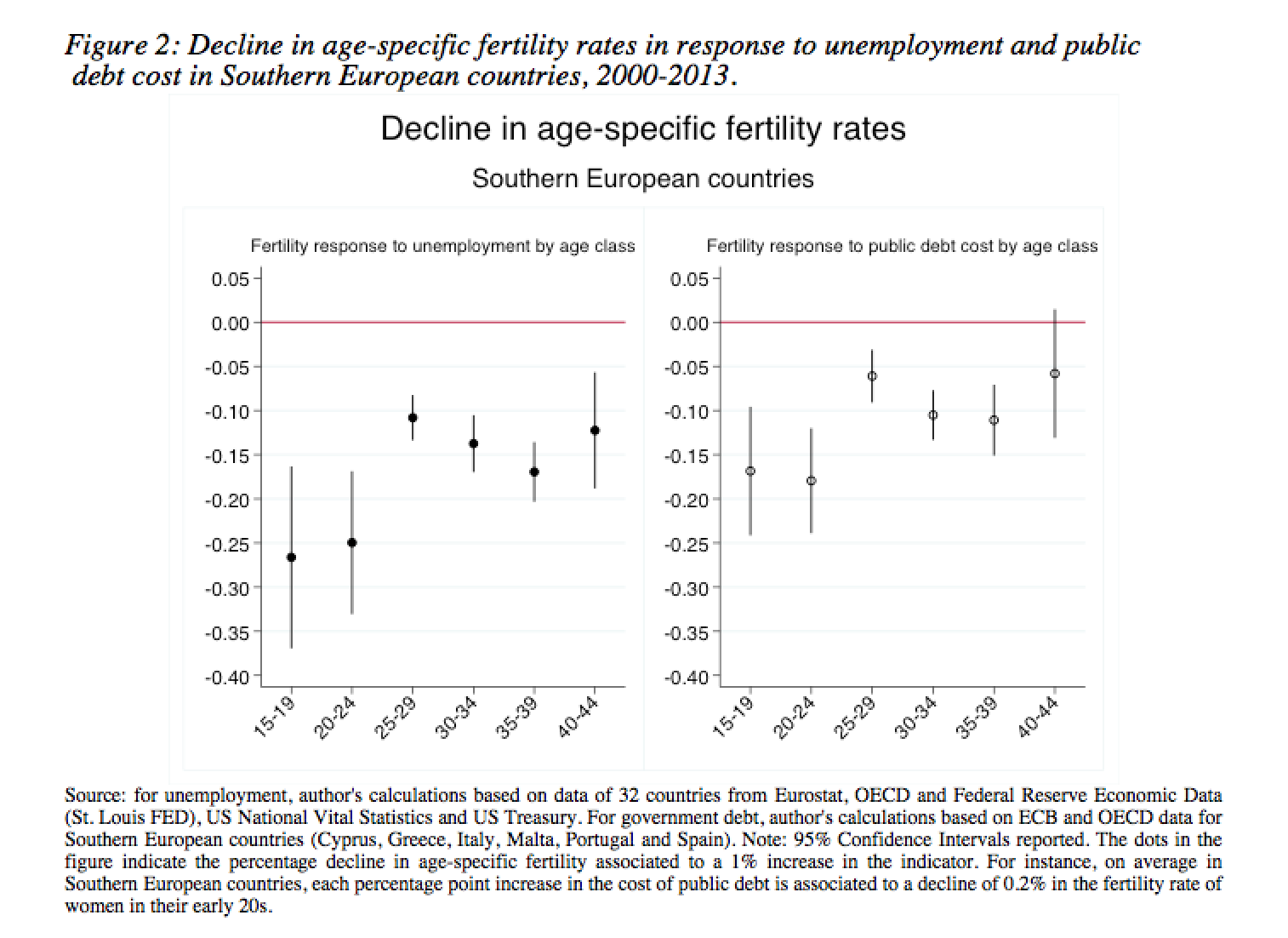

Building on a recent paper by Goldstein and colleagues (2013), in a recent study (Comolli 2017) I analyzed the response of fertility rates to the set of indicators described above: total, youth and female unemployment, sovereign debt risk, economic policy uncertainty (Baker et al. 2012) and consumer confidence in 32 western countries over the period 2000-2013. Figure 2 illustrates the decline in fertility, in different age groups, in response to unemployment and public debt in six Southern European countries. The plots report the percentage decline in the age-group fertility rate associated, in the left panel, to a one percentage point increase in unemployment and, in the right panel, to a one percentage point increase in public debt interest rates (both lagged one year). These two indicators present, in a nutshell, one of the main results of the study. The two images are strikingly similar: in the last 15 years, birth rates declined, among other reasons, not only because of labor market deterioration but also because of the uncertainty about countries’ financial solidity¹. The sovereign debt crisis in Southern European countries raised doubts about countries’ financial stability and the credibility of their governments, and fertility rates reacted negatively to public financial risk – roughly as much as they did to rising unemployment.

Uncertainty drives births down net of unemployment

In addition, my research shows that uncertainty and structural indicators are not substitutes for one another. Instead, they convey information on different, but relevant facets of the Great Recession’s impact on fertility. Despite the high correlation between them, I detect an impact of economic policy uncertainty on fertility rates net of the effect of unemployment. In other words, economic and financial uncertainty inhibits birth rates, over and above the deterioration of labor market conditions (see the paper for more details). This means that even in countries where unemployment rates have returned to pre-crisis levels, feelings of uncertainty about the future still hinder childbearing.

In conclusion, if we limit research to traditional indicators (e.g. unemployment rate), we miss a non-negligible share of the negative effects of the Great Recession on childbearing. This study suggests the need for a broader empirical definition of uncertainty to understand what drives fertility rates during periods of exceptionally high insecurity.

References

Baker, S.R., Bloom, N., and Davis, S.J. (2012). Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Working Paper Series Stanford University.

Comolli, C.L. (2017). The fertility response to the Great Recession in Europe and the United States. Structural economic conditions and perceived economic uncertainty. Demographic Research, 36(51): 1549-1600.

Goldstein, J., Kreyenfeld, M., Jasilioniene, A., and Orsal, D.K. (2013). Fertility reactions to the Great Recession in Europe: Recent evidence from order-specific data. Demographic Research. 29(4): 85−104.

Pison Gilles (2011) Two children per woman in France in 2010: Is French fertility immune to economic crisis? Population and Societies, March, 476: 1-4, Schneider, D. (2015). The Great Recession, fertility, and uncertainty: Evidence from the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family. 77(5): 1144−1156.

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., and Philipov, D. (2011). Economic Recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review. 37(2): 267−306.

Footnote

¹ See the paper for similar results on the complete sample of countries. A similar decline in fertility rates is also found in association to the growing unpredictability of economic policies and the decline in consumer confidence.