Caring for ageing parents reduces fertility intentions in Australia

Ester Lazzari and Valeria Zurla examine how taking on the role of caregiver for a parent influences the expectation to have children. Using prospective data from the Australian HILDA survey, the authors show that becoming a parental caregiver can decrease fertility expectations, particularly among individuals who already have one child.

When parents or parents-in-law experience a decline in health, adult children often step in to provide care. This new role can profoundly affect their plans for the future, including the decision to start or expand their own families. In a recently published study (Lazzari and Zurla 2024), we explored how Australian men and women expecting to have children changed their plans after becoming care givers to their parents.

The issue is especially important today as many people are delaying parenthood and, by the time they are ready to start a family, their parents will be older and more likely to need care.

Balancing caregiving and family plans

When a parent’s health deteriorates, adult children may take on caregiving duties that are both emotionally and physically demanding (Fortinsky et al. 2007). If becoming a caregiver happens at a time when they are planning to have children, it could negatively affect those plans. Two main reasons explain this link. First, caring for an elderly parent takes time and energy, leaving less room to focus on other goals, like building a family. Second, many people rely on their parents for childcare once they have children. If their parents are unwell, this support may no longer be available, leading them to revise their fertility plans.

Previous research in Europe has shown that the informal childcare provided by grandparents often encourages their adult children to have kids (e.g., Aassve et al. 2012; Rutigliano 2024; Rutigliano & Lozano, 2022; Tanskanen & Rotkirch 2014). This is likely true also in Australia, the setting of this study, where grandparents are the most common childcare providers (Baxter 2022).

Parental caregiving may also have positive effects by prompting psychological changes that positively influence fertility plans. For instance, adult children who became caregivers may feel more motivated to continue the family line or to give their parents the joy of becoming grandparents (Rackin & Gibson-Davis 2022).

Fertility expectations decline after caregiving begins

In our study, we examined these connections using survey data from Australia collected between 2001 and 2021. We focused on a sample of men and women of reproductive age who had positive childbearing expectations and analyzed how these expectations evolved over time. We used a difference-in-differences model which compared changes in fertility expectations between two groups: a treatment group consisting of individuals who became caregivers and a control group consisting of similar individuals who did not become caregivers. If becoming a parental caregiver affects fertility expectations, we would expect to see a divergence in the trajectories of the two groups after individuals in the treatment group take on caregiving responsibilities. Moreover, if these two groups have similar trajectories before the event, this suggests that they would have followed comparable patterns if not for their differing experiences with caregiving.

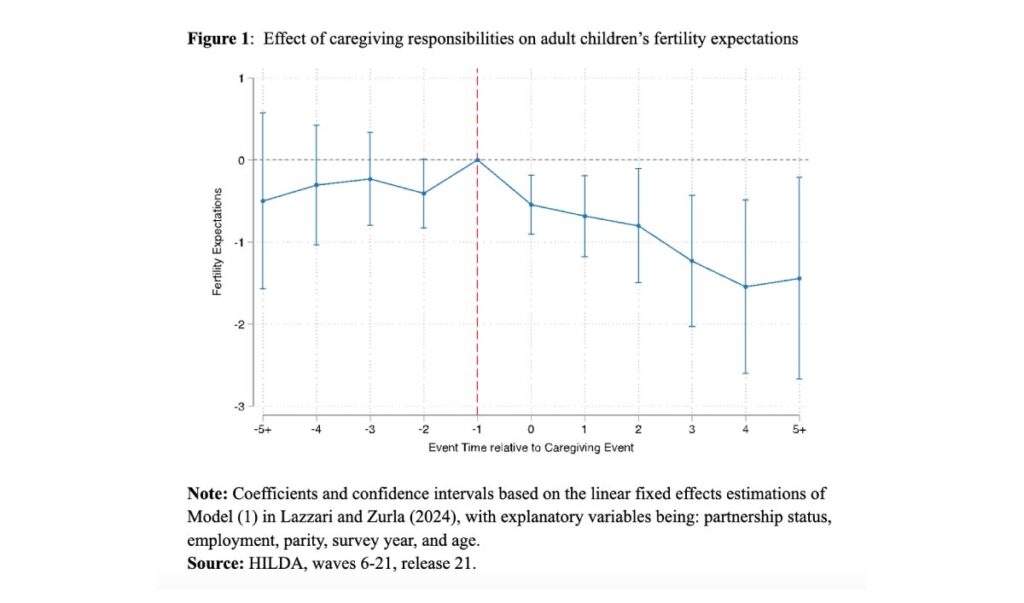

Results are represented in Figure 1. The x-axis indicates the time (in years) relative to the onset of becoming a parental caregiver. The dashed gray line indicates where we would expect the regression coefficients to fall if caregiving had no effect on fertility expectations. The figure indicates that becoming a caregiver results in an immediate and substantial decline in expectations, and that this negative effect intensifies over time. On average, fertility expectations decrease by approximately 7% within the first two years and by 20% three years after the caregiving responsibility begins.

In a separate analysis, we explored how these results vary based on whether caregivers are childless or already have one child. No relevant difference emerges between the two groups in the first two years following the caregiving event. However, after three years, parents with one child experience a more pronounced decline in fertility expectations. This pattern could be attributed to stricter birth timelines among parents. Typically, the interval between the first and second child is 2 to 4 years, and missing this window may lead to a larger drop in expectations compared to individuals with no children.

Implications

While previous research has identified many factors that can lead people to revise their fertility plans, the role played by parental caregiving responsibilities has not been specifically investigated. In this study, we shed light on this link by presenting evidence that an increase in caregiving responsibilities toward parents is likely to have a negative impact on fertility expectations.

Although grandparents can serve as an important source of support for their children planning to start a family, their declining health may present obstacles to family formation. Since health tends to deteriorate with age, individuals who delay family formation are more likely to face the caregiving needs of their aging parents when planning their own families. This may make parental caregiving an increasingly important factor in understanding childbearing choices and suggests that public interventions supporting adult children in their caregiving roles could help alleviate some of the pressures when making childbearing decisions.

References

Aassve A., Arpino, B., & Goisis, A. (2012a). Grandparenting and mother’s labour force participation: A comparative analysis using the Generations and Gender Survey. Demographic Research, 27(3): 53-84.

Fortinsky, R. H., Tennen, H., Frank, N., & Affleck, G. (2007). Health and Psychological Consequences of Caregiving. In C. M. Aldwin, C. L. Park, & A. Spiro III (Eds.), Handbook of health psychology and aging (pp. 227–249). The Guilford Press.

Lazzari, E. & Zurla, V. (2024). The Effect of Parental Caregiving on the Fertility Expectations of Adult Children. European Journal of Population, 40 (online first).

Rackin, H., & Gibson-Davis, C.M. (2022). Familial deaths and first birth. Population and Development Review, 48(4): 1027-1059.

Rutigliano, R. (2024). Do grandparents really matter? The effect of regular grandparental childcare on the second-birth transition. European Sociological Review, 40(5), 772-785.

Rutigliano, R., & Lozano, M. (2022). Do I want more if you help me? The impact of grandparental involvement on men’s and women’s fertility intentions. Genus, 78: 13.

Tanskanen, A.O., & Rotkirch, A. (2014). The impact of grandparental investment on mothers’ fertility intentions in four European countries. Demographic Research, 31: 1-26.