Climate change is caused much more by generalized pursuit of throughput growth and the consumption patterns of the wealthy than by population growth. Structural changes would be needed in global governance, but, George Martine argues, they are highly unlikely in the current political climate.

In my previous N-IUSSP articles (Martine 2016, 2018), I highlighted four key points in the discussions of population/environment (P/E) relations:

a) the pressing nature of environmental threats

b) the diversity within the concept of “population”

c) the inadequacies of solutions focused solely on fertility reduction

d) and the challenges posed by “development”

While these points remain relevant, the passage of time has influenced their relative significance and the way they interact within rapidly-changing geopolitical scenarios. Demographic dynamics continue to have a profound impact on the political, social, economic and environmental landscapes of our society, both at the macro and micro levels. Hence, population policies remain broadly relevant, but their objectives and content need updating.

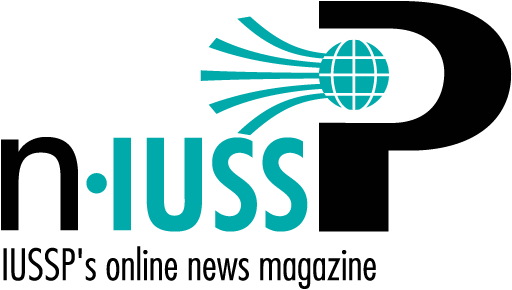

Slower population growth

As a consequence of fertility decline, the global population growth rate has dropped from a peak of 2.3% per year in 1963 to less than 1% today (Figure 1). Despite this, concerns about population growth persist, but in a different perspective. Today, growth is often viewed as a key factor triggering potential ecological chaos, rather than merely as a hindrance to economic growth. This perception is appealing because it favors solutions that absolve “development” of responsibility for ecological threats, while also placing the brunt of the blame on the behavior of people in high-fertility underdeveloped countries. However, this apparently straightforward relationship is neither simple nor practical. Indeed, the intense focus on population-environment interactions centered solely on demographic growth diverts attention from the structural actions needed to mitigate the risk of ecological chaos.

The climate change crisis

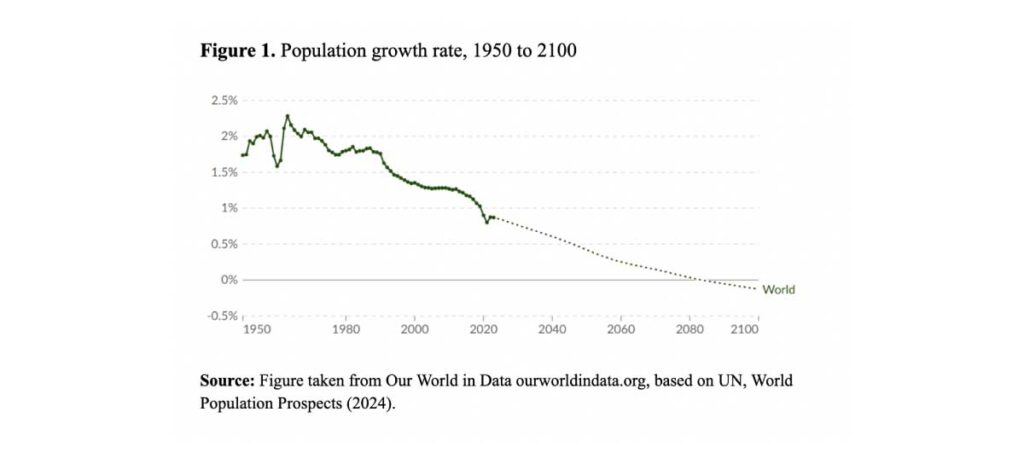

A constant increase in the number and intensity of climate-related disasters daily confirms science’s repeated warnings about the urgent threats faced by our civilization (Hansen et al. 2025). Despite these alerts, die-hard negationists, moved by near-sighted political and economic objectives, defy this obvious peril. The risk of severe environmental disruptions and the disintegration of global governance underscore the need for decisive action.

What actions are being taken to deviate from the current hazardous course? The will and capacity of global governance to deal with these issues is at a perilously low ebb, as the optimistic promises of globalization have warped into ultra-nationalism, wherein economic goals are prioritized above all others. The 2015 Paris Agreement pledged efforts to limit global temperature to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels in order to keep climate change within manageable limits. These promises were clearly insufficient and eventually ignored altogether. Consequently, as seen in Figure 2, the last decade has been the warmest on record, with the year 2024 being the first calendar year in which the average global temperature exceeded 1.5°C above its pre-industrial level.

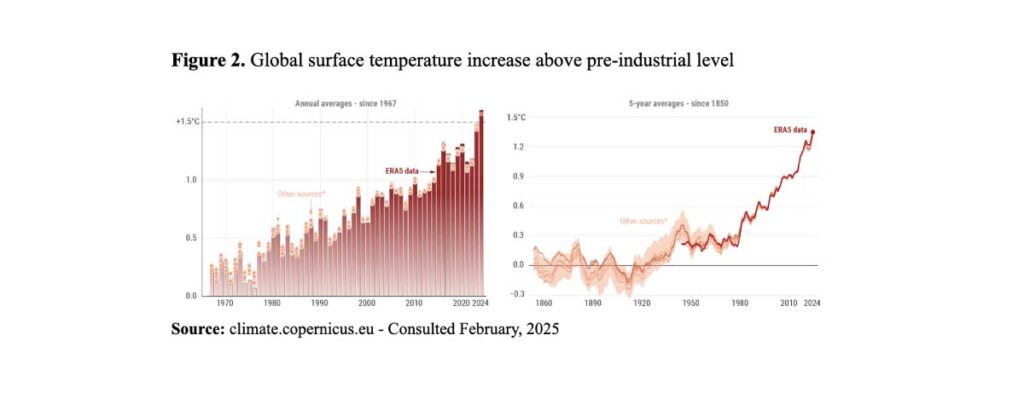

Acknowledging diversity and size in “population”

Relations between population dynamics and environmental outcomes continue to be critical. Nevertheless, it is erroneous to lump all humans into the broad amorphous category of “population” for purposes of policy formulation. Enormous socio-economic disparities between social groups condition vastly-differentiated pressures on the environment. Emissions are accelerating, but they are driven largely by the actions of the richest people worldwide (Figure 3). Africa is home to 18.4% of the world’s population, but accounts for some 4% of total CO2 emissions; meanwhile, the USA has 4.2% of the world’s population but accounts for 14.4% of current emissions and 25% of all historical emissions.

Birth control policies, CO2 emissions and global governance

Today, reproductive health initiatives continue to be critical for women’s health and gender equity, but not for future population control since the effects of population control policies are slow-moving and gradual, for several reasons, including demographic inertia. Global growth rates are now declining steadily and no population control policy can accelerate this pace over the short term, even under draconian systems. By comparison, the impacts of our primary ecological threat – climate change – are short-term. Given the overwhelming thrust of scientific predictions regarding the proximity of grave and irreversible environmental chaos, further fertility declines – with or without population control efforts – would only impact environmental threats well after our system passes the dreaded 2.0oC barrier.

Evidently, past fertility patterns are having an enormous impact on current emissions, but birth control does not have retroactive effects on population size or on the environment. Despite implementing stringent fertility reduction programs and experiencing intermediate levels of per-capita emissions, China now has total emissions that surpass those of the United States and the European Union combined. Similarly, India has relatively low per-capita emissions but ranks third highest in total emissions worldwide. This warns us that current rates of population growth will only be relevant for long-term sustainability if our civilization were to decouple growth from resource throughput in coming decades. However, the likelihood of that happening appears minimal in the current context.

Climate change is a global problem and demands global responses in order to modify a system based on the destruction of resources for the promotion of increasing consumption. Population dynamics impact the environmental quandary within the context of our civilization’s primary quest, i.e. – “development by throughput economic growth”. This generalized pursuit is what puts the planet’s natural resources and sink capacity in jeopardy.

Earlier perceptions of development/environment relations did not anticipate the effects of vigorous nationalistic competitivity and the surge of populist governments that globalization has inspired. Environmental concerns have become secondary in this framework. Left-wing governments proclaim pro-environmental platforms but, in practice, choose “growth” over “environment” in order to compete in the economic terrain. Right wing populists prioritize growth, negate the existence of environmental threats, and dismiss effective initiatives outright.

Environmental denial is compounded by disregard for social inequalities. The same geopolitical systems and structures that promote consumerism and burden the poor with the worse consequences of climate change also favor disregard for the social justice issues and the global economic inequalities that are found at the heart of climate change. Right-wing populists attack civilizational policies that promote equity and well-being and withdraw from multilateral humanitarian programs, in such critical areas as human rights, health and foreign aid. These attitudes not only dismantle global solidarity and governance but also intensify ecological threats. They also have direct consequences for population dynamics, as illustrated in the USA where attempts to “whiten” the population, by reducing access to reproductive health and banning abortion, are leading to higher fertility and infant mortality rates (Martine, 2024).

Implications

Rising global temperatures and the increasing frequency and severity of “natural” disasters linked to climate change compel humanity to shift its focus from misleading solutions in order to concentrate on critical governance issues that can only be resolved at the global level. However, the current global context is not conducive to “appropriate policies” in general. In the population field, a wider array of issues needs to be addressed by a refurbished global governance and a more humanitarian ambiance. Denying access to reproductive health constitutes a huge step backwards for humankind. Anti-immigration policies are self-serving in view of the vulnerabilities of the global South caused by “development”, but they are also self-defeating in the context of other contemporary demographic issues, such as population decline and ageing. Unfortunately, global and national efforts to deal effectively with these complex issues may only be sparked, belatedly, by the consequences of even more destructive environmental calamities.

References

Hansen J.E. et al. (2025) Global Warming Has Accelerated: Are the United Nations and the Public Well-Informed? Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 67:1, 6-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2025.2434494

Lu M., Vendetti B. (2023) Charted Emissions by Income Group, Visual Capitalist, December 15.

Martine G. (2016) Sustainability and the missing links in global governance, N-IUSSP.

Martine G. (2018) Global population, development aspirations and fallacies, N-IUSSP.

Martine G. (2024) Shifting politics and the makeover of birth control policies. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Populacionais. v.41, 1-23, e0273.

Source figures

Source figure 1 • https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/population-growth-rates

Source figure 2 • https://climate.copernicus.eu/copernicus-2024-first-year-exceed-15degc-above-pre-industrial-level