The rise of divorce, separation, and cohabitation in the Philippines

“What God has put together let no man put asunder”. This biblical quote is frequently heard among Filipinos, particularly among the older generations, to discourage young people from leaving an unsatisfactory marriage. The indissolubility of marriage is also strongly advocated by the Catholic Church, to which 80% of Filipinos belong.

Philippines: the only country in the world where divorce is not legal

The Church’s strong opposition to divorce is probably the main reason why the Philippines is the only country in the world, together with the Vatican, where divorce is not legal. Except for Filipinos who are married to foreigners and seek divorce in another country, and for Muslim Filipinos who are governed by different marriage laws¹, about 95% of Filipinos need to file a nullity of marriage or an annulment² to legally terminate their marriage. However, only a small fraction resort to these remedies because, while the outcome is uncertain, costs are high (usually not less than three months of average labour earnings, and sometimes much more) and the legal procedures are long and complex. Completing a matrimonial dissolution case typically takes between six and eighteen months but the procedure can also extend over several years (Lopez, 2006).

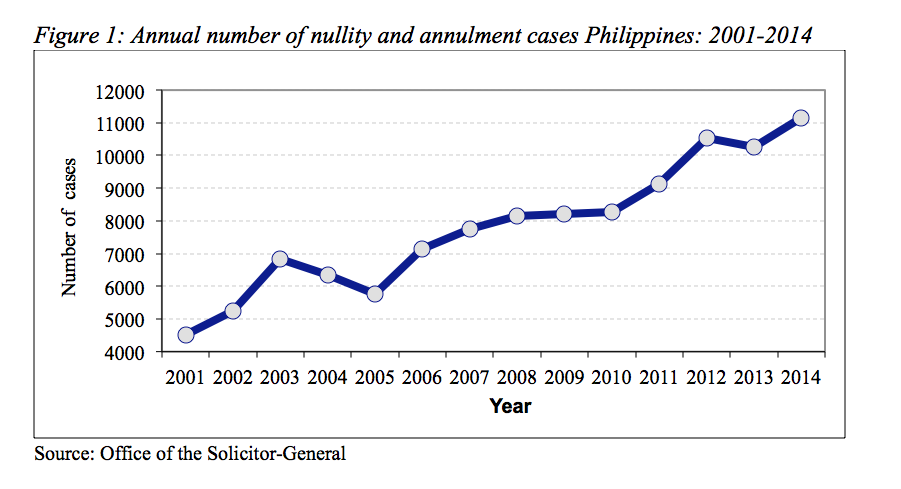

Most Filipinos who wish to end their marriage resort to informal separation. Ideally, couples need to apply for a legal separation that provides them with legal sanction to live separately, but in reality most couples, especially the poor, just live separately without going through this legal procedure. Although most Filipinos still value marriage, the proportion who separate from their spouse, both legally and informally, is increasing. Figure 1 shows that the numbers of annulment and nullity cases filed at the Office of the Solicitor-General (OSG) has increased from 4,520 in 2001 to 11,135 in 2014. Census and survey data also show a similar trend.

On the likely causes of the rise of divorce and separation in the Philippines

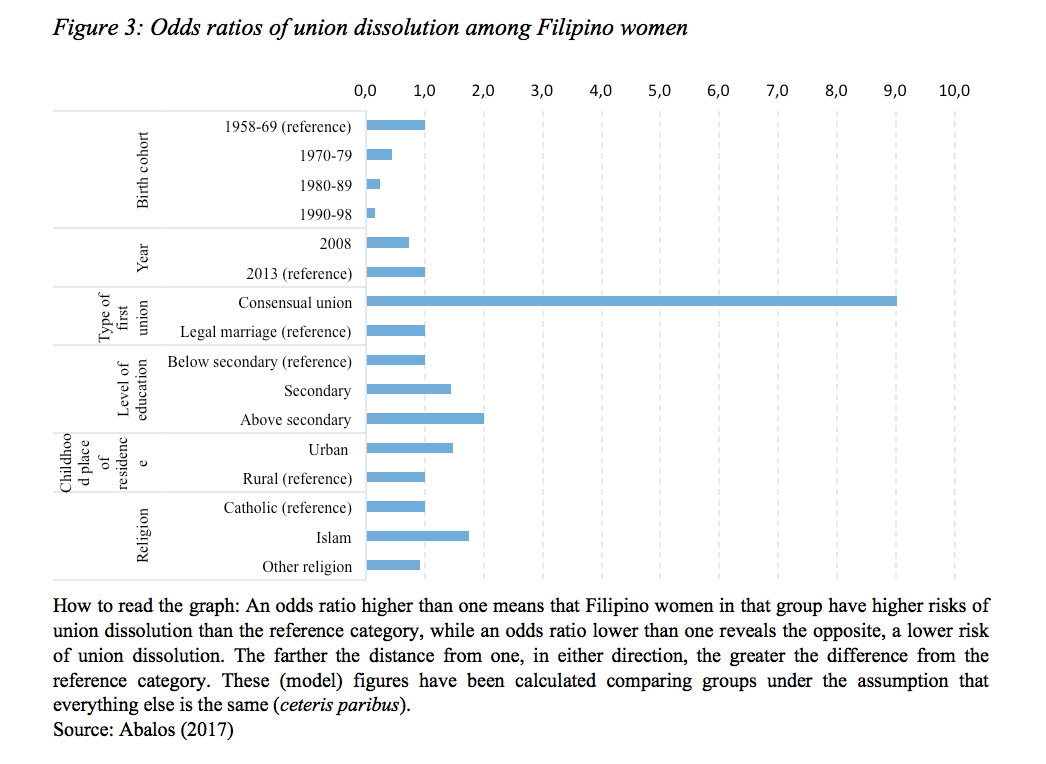

The increase in union dissolution has been accompanied by a parallel increase in the proportion of Filipinos who live together with their partner without marrying. In the past two decades, the proportion of cohabiting Filipino women of reproductive age almost trebled, from 5.2% in 1993 to 14.5% in 2013 (Abalos 2014; PSA and ICF 2014). As cohabitation has much higher dissolution rates than formal marriage (Figure 3), the rise in cohabitation will likely lead to an increase in the proportion of Filipinos who are separated³. The rise in cohabitation may also be attributable to the country’s “marriage crisis”: cohabitation may be preferable to marriage precisely because it is relatively easier and cheaper to end.

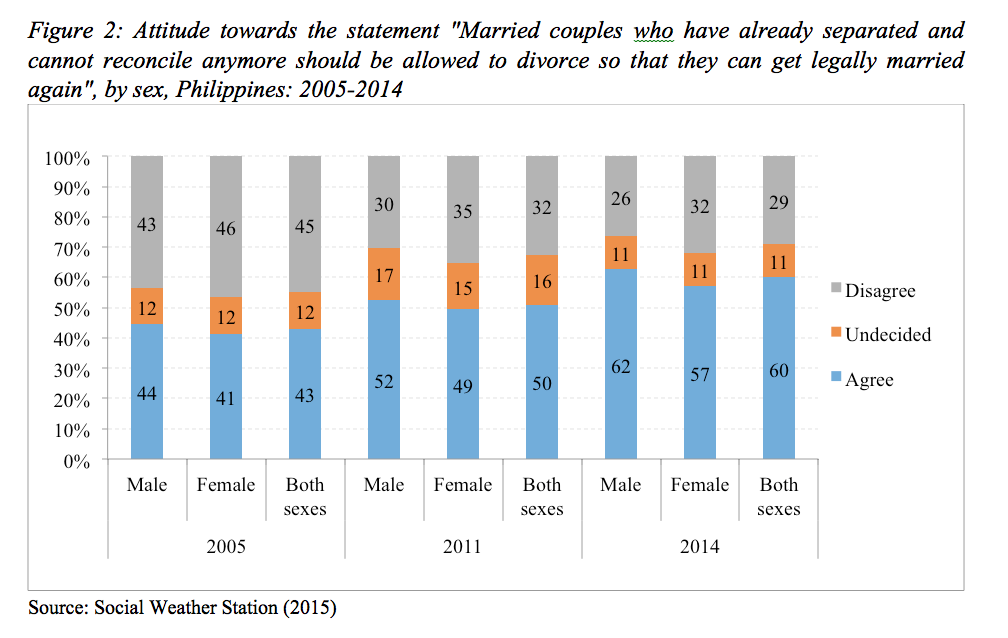

While most Filipinos still hold conservative views about marriage and divorce, a growing segment of the population is becoming more receptive to the idea of divorce. Figure 2 shows that over the last decade the proportion of Filipinos who agreed that “Married couples who have already separated and cannot reconcile anymore should be allowed to divorce so that they can legally marry again” increased from 43% in 2005 to 60% in 2014. This growing acceptance of divorce may have contributed to reducing the stigma of being divorced or separated, particularly among women, who were, and still are, expected to make all possible efforts to keep their marriage intact.

The increasing exposure of Filipinos to the urban environment (42.4% were city dwellers in 2007 and 45.3% in 2010) has probably contributed to this growing liberal attitude towards divorce. Urbanization is commonly associated with non-traditional lifestyles and behaviors, and reduces the influence of the extended family on the decisions of young people, including mate selection. This means that children do not feel obliged (by their parents’ choice) to stay in a marriage when it has become unbearable. This constitutes a break from a still recent past when parents and other family members exerted strong pressure on couples to keep their marriage intact in order to strengthen family bonds and protect the family’s reputation.

Which women are most likely to dissolve their union?

Figure 3 shows the odds ratio or the relative probability of being divorced and separated among Filipino women, controlling for different factors. Highly educated Filipino women have higher odds of dissolving their union than women with lower levels of education. Higher education in the Philippines improves the economic status of women and is more likely to provide them with financial independence. Indeed, a key factor for Filipino women when they leave their husband is their ability to support themselves and their children. This sense of independence and empowerment also enables women to transcend the social stigma of being divorced or separated.

Filipino women who grew up in urban areas are also more predisposed to union dissolution than women who were raised in rural settings. The traditional values and ideals instilled among women in rural areas and familial pressure to keep the marriage intact for the sake of their family’s reputation (Medina 2015) may also have contributed to the lower likelihood of union dissolution among women who were reared in rural areas.

Will the Philippines finally join the rest of the world in legalizing divorce?

As cohabitation becomes more common and as more Filipinos come to embrace more unconventional views toward marriage and divorce, the increase in union dissolution in the Philippines is unlikely to slow down in the coming years. The continued expansion of educational opportunities for women and the growing mobility of young people to urban areas will also contribute towards the steady increase in union breakdowns among Filipinos. With the recent change in leadership in the Philippines, the political atmosphere has also become more open to laws opposed by the Catholic Church, as evidenced by the strong support for the revival of the death penalty. Despite this, the Catholic Church remains a force to be reckoned with in terms of divorce legislation in the Philippines.

References

Abalos, J.B. (2014). Trends and determinants of age at union of men and women in the Philippines. Journal of Family Issues 35(12): 1624‒1641.

Abalos, J.B. (2017). Divorce and separation in the Philippines: Trends and correlates. Demographic Research 36 (50): 1515-1548. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.50.

Fenix-Villavicencio, V. and David, R.J. (2000). Our right to self-determination: PILIPINA’s position on the issues of divorce and abortion. Quezon City:PILIPINA.

Gloria, C.K. (2007). Who needs divorce in the Philippines? Mindanao Law Journal 1: 18‒28.

Lopez, J. (2006). The law of annulment of marriage rules of disengagement: How to regain your freedom to remarry in the Philippines. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing.

Medina, B.T.G. (2015). The Filipino family. 3rd edition. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

PSA and ICF – Philippine Statistics Authority and ICF International (2014). Philippines National demographic and health survey 2013. Manila and Rockville: PSA and ICF International.

Social Weather Stations (SWS) (2015). Fourth quarter 2014 Social Weather Survey: 60% favor legalization of divorce; was 50% in 2011 and 43% in 2005 [electronic resource]. Quezon City: Social Weather Stations.

¹ The Code of Muslim Personal Laws was passed in 1977. It allows Muslim marriages to be governed by Islamic Law, thereby permitting divorce for Muslim Filipinos. However, no similar law was passed to allow marriages solemnized in accordance with the traditions of other indigenous groups to be governed by their own indigenous laws (Gloria 2007: 19).

² A declaration of nullity of marriage presupposes that the marriage was not only defective but also null and void at the time it was celebrated. While, by annulment, the marriage is declared to have been defective at the time of celebration, it is considered valid until the time it is annulled (Fenix-Villavicencio and David 2000).

³ Filipino women who have cohabited but no longer live with their partner are categorized as “separated” in official surveys in the Philippines.