Stefania Molina’s research reveals that, in Colombia, separated and cohabiting mothers experience higher levels of intimate partner violence during pregnancy than married mothers. Disparities in low birth weight across partnership statuses are primarily linked to maternal characteristics and differences in access to antenatal care.

Family life is changing rapidly around the world, and Colombia is no exception. Over the past few decades, marriage has become less common, with more mothers raising their children within cohabiting relationships (living with a partner and not married) or on their own. This shift reflects deeper social transformations and has sparked interest in understanding how different family forms influence the lives of mothers and their children.

Unmarried mothers often face greater social and economic challenges than their married counterparts. These include limited access to resources, fewer opportunities for support, and increased stress, all of which can negatively affect maternal well-being and the development of their children. Studies suggest that such factors play a key role in poorer health outcomes for children (Brown, 2010), including low birth weight (LBW, below 2,500 grams), an important indicator of infant health.

Another factor shaping this dynamic is intimate partner violence (IPV), which is common during pregnancy in many parts of the world, including Colombia. IPV during pregnancy not only endangers the mother but may also harm the unborn child through increased stress, trauma, or reduced access to prenatal care. Furthermore, IPV levels are not evenly distributed across family forms. Women in less stable or non-marital partnerships are often at greater risk (Friedemann-Sanchez and Lovatón, 2012), raising important questions about how family dynamics influence experiences of IPV and the health of both mothers and their children.

In a recent study (Molina, 2025), I investigated the implications of Colombia’s shifting family forms for infant health, focusing on IPV and its relationship to maternal partnership status. The study draws on data from the Colombian Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted in 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015.

Cohabitation: the norm for mothers in Colombia

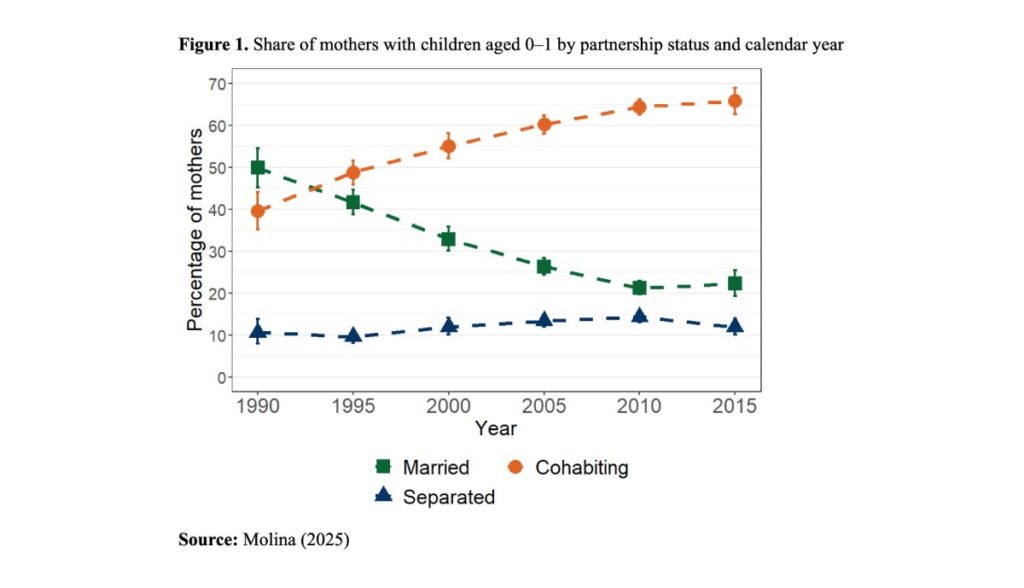

Unmarried motherhood is rising globally, but Colombia offers a unique case. In 2015, 65.8% of mothers with children aged 0-1 were cohabiting, while only 22.3% were married (Figure 1). This trend reflects Colombia’s history, where consensual unions have long been a significant part of family life due to cultural and historical influences (De Vos, 2000). Today, cohabitation has become the leading family form, extending beyond less advantaged groups to include highly educated mothers.

Intimate partner violence during pregnancy

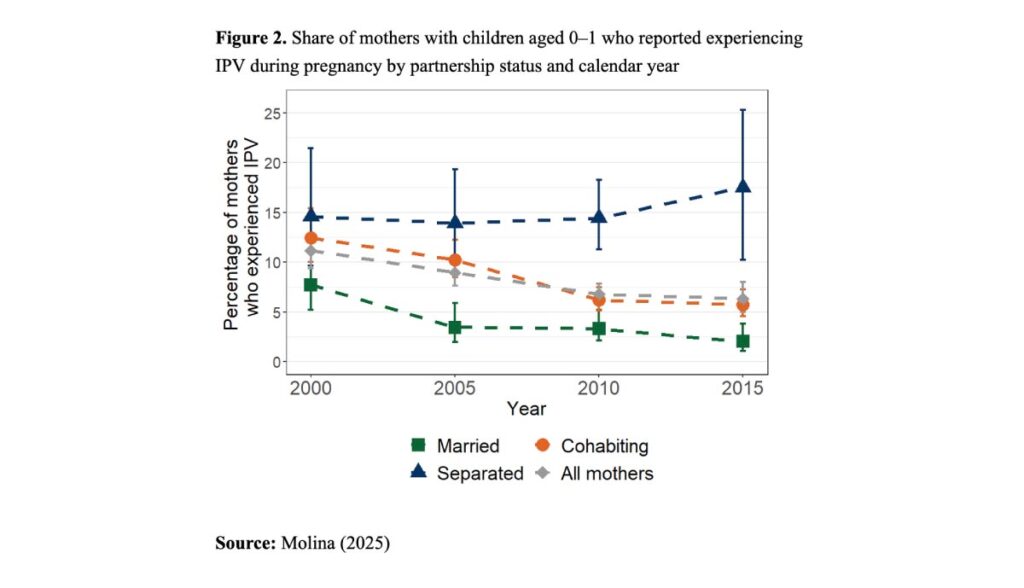

IPV during pregnancy remains a severe public health problem with widespread consequences for maternal and child well-being (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006). In my study, I found that separated and cohabiting mothers report notably higher IPV levels than married mothers.

From 2000, reported levels of IPV among cohabiting mothers declined over time, while separated mothers continued to report high levels. This decline could be attributed to changes in the composition of cohabiting mothers, as this family form includes women from increasingly diverse social and educational backgrounds. By 2015, however, 17.5% of separated mothers and 5.8% of cohabiting mothers with children aged 0–1 were still reporting experience of IPV during pregnancy, compared to just 3.7% of married mothers (Figure 2).

Additionally, IPV itself might influence family transitions, with violence potentially contributing to separation. As societal acceptance of separation following IPV grows, the higher IPV levels among separated mothers may reflect this evolving social norm.

Intimate partner violence and infant health

The relationship between IPV and infant health is complex and multifaceted. While unmarried mothers are more likely to have infants with LBW, much of this disparity stems from differences in maternal characteristics, such as education and age, and inequities in antenatal care. For example, compared to cohabiting or separated mothers, married mothers are significantly more likely to attend the recommended eight or more antenatal visits, which have a considerable impact on reducing LBW risks.

Surprisingly, IPV during pregnancy was not found to have a direct association with LBW. This could reflect the complexity of examining LBW – which is influenced by multiple factors beyond IPV – as a health outcome. Moreover, the relatively low prevalence of LBW in the data adds to the challenge of detecting such relationships. Additional analysis revealed that IPV during pregnancy is closely linked to an increased likelihood of pregnancy loss, suggesting that its most profound effects might actually occur before birth.

Conclusions

These findings reveal a complex interaction between changing family forms, intimate partner violence, and maternal and child health in Colombia. The increase in cohabitation and separation reflects shifting social norms, but these changes also highlight enduring gender inequalities. Mothers who are separated or in cohabiting unions face unique challenges, including higher rates of IPV and reduced access to healthcare, which affect child health outcomes such as LBW.

To improve maternal and child health outcomes, Colombia must strengthen healthcare services for unmarried mothers, ensuring equitable access to antenatal care. At the same time, addressing IPV requires a multifaceted approach that considers the varying risks across different partnership statuses. Finally, tackling the broader social and economic inequalities that exacerbate IPV and family instability will be critical to fostering healthier outcomes for mothers and their children.

References

Brown, S. (2010). Marriage and child well-being: Research and policy perspectives. Journal of Marriage and Family 72(5): 1059–1077.

De Vos, S. (2000). Nuptiality in Latin America: The view of a sociologist and family demographer. In: Browning, S.L. and Miller, R.R. (eds.). Till death do us part: A multicultural anthology on marriage. Stanford: JAI Press: 219–243.

Friedemann-Sanchez, G., and Lovatón, R. (2012). Intimate partner violence in Colombia: Who is at risk? Social Forces 91(2): 663–688.

Garcia-Moreno, C., Jansen, H.A., Ellsberg, M., Heise, L., and Watts, C.H. (2006). Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. The Lancet 368(9543): 1260–1269.

Molina, S. (2025). Unmarried motherhood and infant health: The role of intimate partner violence in Colombia. Demographic Research, 52(6), 141–178.