Little is known about the composition of kinship groups and family members outside the household, and how this evolves by age and over time. Martin Kolk and colleagues, exploiting exhaustive Swedish register data, shed full light on this aspect, with reference to the Swedes alive in 2017. The patterns they find by age confirm expectations while also revealing overlooked aspects.

Surprisingly little is known about the composition of kinship groups and family members outside the household. Although demographers have a reputation for counting things, very few studies have counted kinship networks in contemporary societies. The lack of data is unfortunate as the extended family forms an important part of an individual’s social network and can provide significant support, ranging from child rearing and elder care to financial assistance. As recent research on social stratification indicates, the extended family background is also important for life chances in contemporary societies (Hällsten & Kolk 2022; Mare 2011).

The dynamics of kinship in Sweden

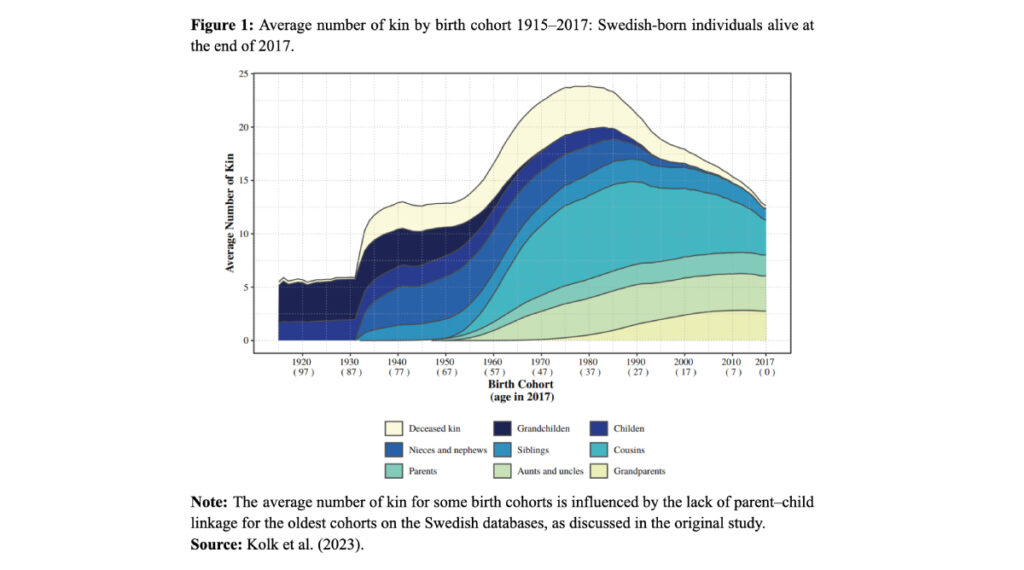

In a recent study, my coauthors and I documented kinship in Sweden using Swedish administrative registers (Kolk, Andersson, Pettersson, & Drefahl, 2023). We counted the averages and distributions of kin such as grandchildren, children, nieces, nephews, siblings, cousins, parents, parents’ siblings, and grandparents, and we examined these relationships longitudinally, because kinship varies considerably over the life course, both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Figure 1 shows the average number of different categories of kin for Swedes of different ages observed in 2017. People in their mid-30s have the most relatives, about 20, while young children have about 15, and 70-year-olds have about 10. Not surprisingly, older people have more relatives in the descending line, such as grandchildren, while the young have the more relatives in the ascending line, such as parents and grandparents. People in mid-life have a large number of relatives in the same generation, such as siblings and cousins. Swedes in their mid-30s, for instance, have 8 cousins on average, and almost 30 percent have 11 or more. In our original study (Kolk, Andersson, Pettersson, & Drefahl, 2023), we provide more detailed figures for each category of kin, and we look at how factors such as sex, lineage (e.g. maternal and paternal grandparents) and family complexity (e.g. half-siblings) affect the number and type of relatives people have.

A strongly variable phenomenon

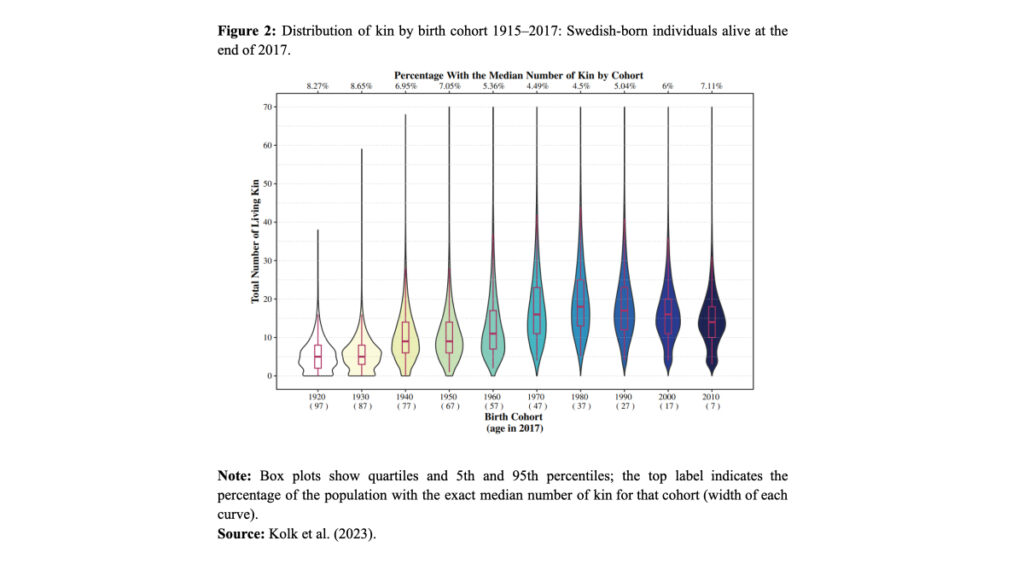

Figure 2 shows that the number of relatives the Swedes have varies considerably, depending on who, and how old they are. Some people have very few relatives, only 3 or 4, while others have more than 45. It is very rare to have no relatives at all: this only happens in some exceptional cases among very old people. The family networks of men and women are very similar. Over time, the proportion of relatives who are the result of separations, such as half-siblings, tends to increase.

A few characteristics of our study and some conclusions

We used Swedish register data to conduct our study, which covers all Swedish-born people living in Sweden in 2018. We used birth records and the unique Swedish national identity numbers to create family networks and count the number of relatives for each person. However, our study only focused on Swedish-born individuals because we did not have demographic data for people living outside Sweden. This means that some relatives, especially grandparents, were missing for people with foreign-born parents.

We think that kinship in contemporary societies should be studied more fully. The last decades have seen substantive work on what kin do, for example, as the recipients or providers of elder care, as well as their role in social mobility. In contrast, we know much less about who has kin and of what type. Here, and in our scientific paper, we give a full demographic account of kinship in one high-income society, but the patterns we find are, of course, specific to the Swedish demographic context. Whether the distributions or relatives by type and age that we found are standard or idiosyncratic is something that cannot be determined until similar data are collected for other countries and other periods.

References

Hällsten, M., & Kolk, M. (2022). The Shadow of Peasant Past: Seven Generations of Inequality Persistence in Northern Sweden. American Journal of Sociology, 128(6), 1716-1760.

Kolk, M., Andersson, L., Pettersson, E., & Drefahl, S. (2023). The Swedish Kinship Universe – A demographic account of the number of children, parents, siblings, grandchildren, grandparents, aunts/uncles, nieces/nephews, and cousins using national population registers. Demography, available online, 10955240.

Mare, R. D. (2011). A multigenerational view of inequality. Demography, 48(1), 1-23.