Homogamy among high-income partners drives up family income inequality

More married couples today consist of two high-income or two low-income partners (i.e., income homogamy), which leads to greater income inequality in married-couple families. Yifan Shen shows that, all else being equal, increases in income homogamy among high earners are always more influential in shaping the level of income inequality among couple-headed families.

Demographers contribute to the study of household income inequality by highlighting the importance of demographic forces such as marriage and family structures. Since most men and women form families, the income correlation between husbands and wives is a demographic factor that can shift the level of family income inequality even if there is no change in the individual income distribution (Lam 1997). If more couples consist of two high-income or two low-income partners (i.e., income homogamy rises), the inequality between couple-headed families will intensify. Further, a rising concentration of economic resources among high-powered, dual-career couples may enhance the family-based advantage among children, which may propagate the inequality of opportunity across generations.

Why should we care?

Academic researchers and nonacademic readers are interested in this topic perhaps for different reasons. For the former, the primary goal is to gain a deeper intellectual understanding of this phenomenon, even if it may not have explicit policy implications. Although most researchers are aware that a higher husband-wife income correlation increases income inequality between families, few have considered a further, more nuanced side of the phenomenon: if the level of income homogamy increases, say, by 10% among high-income husbands and their wives, is its impact on between-couple income inequality the same as a similar 10% increase in income homogamy among low-income couples? In other words, does the increase in income homogamy at each level of income contribute equally to between-couple inequality? A better understanding of this question can help researchers identify the subpopulation group that is more relevant to this demographic process of income inequality generation (Liao 2016).

For nonacademic readers, perhaps a more puzzling question is: why should I care about this phenomenon? Rich people tend to marry each other, so what? This is their personal affair. Nothing can be done about it, even if their private decisions may worsen inequality at societal level (Nozick 2013). This is certainly a legitimate concern and many academic researchers probably share it.

Thought experiment

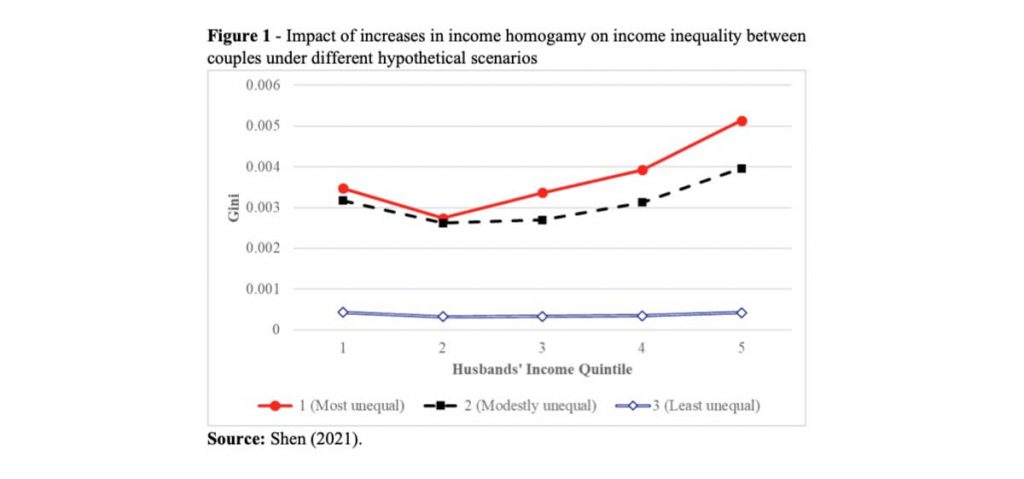

Both questions can at least be partly answered by a thought experiment (Shen 2021). Suppose in a hypothetical world we have three societies that consist of only married men and women. The overall income distributions of married men and women are most unequal in Society 1, modestly unequal in Society 2, and least unequal in Society 3. Further, assume that all men and women within each society are randomly matched with each other in terms of income (so the husband-wife income correlations are zero in each society). Within each society, we order couples by husbands’ incomes from high to low and divide them into five equal-sized groups (quintiles). This is the initial setting of the experiment.

Now, the experiment begins. Within each society, we rematch the top quintile of husbands and their wives assuming perfectly positive matching on their incomes while preserving the baseline pattern of random matching among couples in the other four quintiles. We conduct this quintile-specific rematching one quintile at a time, from the top to the bottom quintile. We end up with six data sets: one baseline data set of randomly matched couples (initial setting) and five new data sets of partially positively rematched couples. We then compute the difference in between-couple inequality between the baseline data set and each of the five new data sets. This gives us a quantitative assessment of the impact on between-couple inequality of increases in husband-wife income correlation (from zero correlation to perfect correlation) at different parts of the income distribution.

Figure 1 shows the results. The impact of increases in income homogamy on between-couple inequality (as measured by Gini index) is far from linear. As long as there is some degree of inequality in husbands’ and wives’ income distributions (i.e., in Society 1 [solid line] and Society 2 [dashed line]), income homogamy increases inequality more when it happens in the top quintile than when it happens in the middle and low quintiles. Because income distributions in real life are always unequal, we can conclude with confidence that increases in income homogamy among high earners always have the largest impact on inequality (holding other conditions constant).

Figure 1 also conveys another message — the impact of income homogamy on between-couple inequality is multiplicative. Increases in income homogamy intensify between-couple inequality, and their disequalizing impact is stronger in societies where incomes are more unequally distributed among married men and women. In the extreme scenario represented by Society 3, in which the income distributions among husbands and wives are very equal, even a drastic transition from random matching to perfect homogamy generates very little inequality between couples (i.e., the dash-dotted line is much lower than the two other lines).

Implications

Returning to our nonacademic question, why should we care about this topic? After all, even if we spend great efforts studying the relationship between income homogamy and inequality, we are still unable to address the inequality that stems from homogamy, as people are free to decide whom they marry. Now we have a partial answer: even though we can do nothing, or should not do anything even if we could, to interfere with high income “homogamy” among high earners, its undesirably large impact on between-couple inequality can still be mitigated by progressive policies – if such policies can reduce the overall income inequality among individual men and women – because when the overall income inequality is reduced, the inequality impact of increases in income homogamy is also reduced. This finding provides an additional rationale for progressive policies that aim at reducing overall income inequality.

References

Lam, D. (1997). Demographic Variables and Income Inequality. In M. R. Rosenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of Population and Family Economics (pp. 1015–1059). Elsevier Science B.V.

Liao, T.F. (2016). Evaluating Distributional Differences in Income Inequality. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 2, 1–14.

Nozick, R. (2013). Anarchy, state, and utopia (Reprint Edition.). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Shen, Y. (2021). The Nonlinear Linkage Between Earnings Homogamy and Earnings Inequality Among Married Couples. Demography, 58(2), 527–550.