Drivers of fathers’ parental leave uptake in Belgium

Using longitudinal register data for Belgium, Jonas Wood, Leen Marynissen and Dries Van Gasse find that fathers who earn less than their female partners are more likely to use parental leave, yet only among higher-earning couples and fathers working in female-dominated sectors of employment.

The dynamics of parental leave uptake in couples have received increasing attention in recent years. This reflects greater societal awareness of issues relating to gender equality and work-life balance, but is also a result of the relatively low rate of parental leave uptake by fathers in many countries. A large body of academic literature has proposed several complementary explanations for differences in fathers’ parental leave uptake, including parenting ideologies and policy design features.

The relative resources hypothesis

Micro-economic considerations are also important. Among these, the relative resources hypothesis posits that the partner with lower wage potential is more likely to use parental leave because this minimizes forgone household income. Consequently, higher parental leave uptake is to be expected among fathers whose wages are lower than their partner’s (i.e., who are the secondary earner within the couple). However, despite being often referred to as a micro-economic determinant of couples’ decision-making (e.g. regarding the gender division of paid labour), we still do not fully understand whether and when the relative resources hypothesis holds as an explanation for low male parental leave uptake.

Secondary-earner fathers are more likely to use parental leave

In a recent study (Wood, Marynissen, Van Gasse 2023), we used large-scale longitudinal register data for Belgium to quantify the significance and magnitude of the relative resources pattern in fathers’ parental leave uptake. A subsample of 1,810 couples was observed longitudinally throughout the father’s period of eligibility for parental leave. Logit models of fathers’ parental leave uptake were estimated, classifying fathers in three levels of relative contribution to the household labour income: less than 40%, 40%‒60%, and more than 60%.

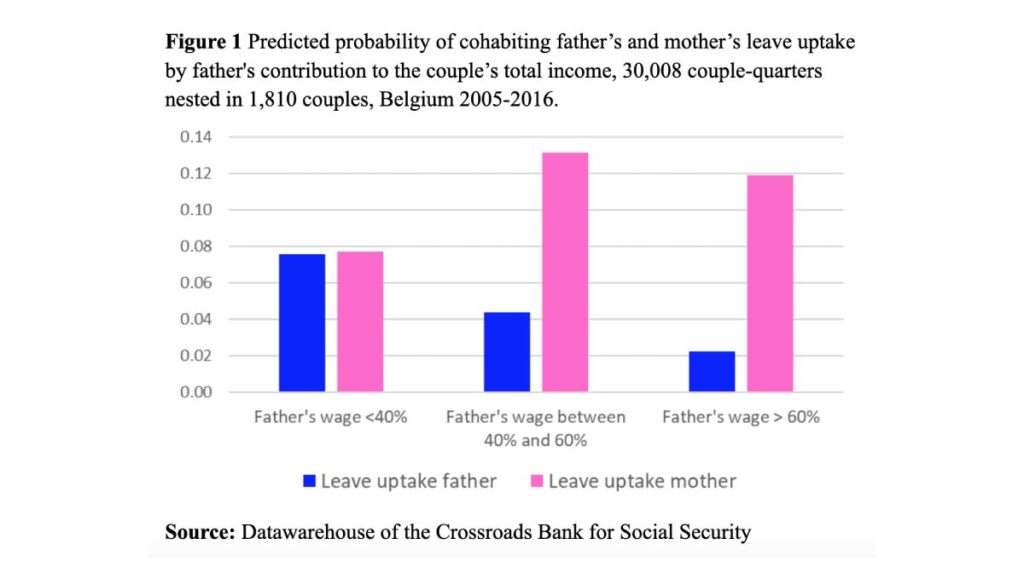

Results confirm that the lower the father’s contribution to household labour income, the higher the probability that he will use parental leave (Figure 1). However, this does not imply that household income constellations where the father is the secondary earner translate into higher male than female leave-taking. Additional models estimating female leave uptake in couples indicate that even within couples with a secondary-earner father (i.e. fathers’ wage <40%), the probability of the father taking parental leave does not exceed that of the mother (Figure 1).

When is it about the money?

In a second stage, we also combined quantitative register-based analyses and qualitative in-depth interviews to explore four factors that potentially moderate relative resources mechanisms in fathers’ leave-taking decisions: household income, workplace factors, incomplete information, and gendered parenting ideals.

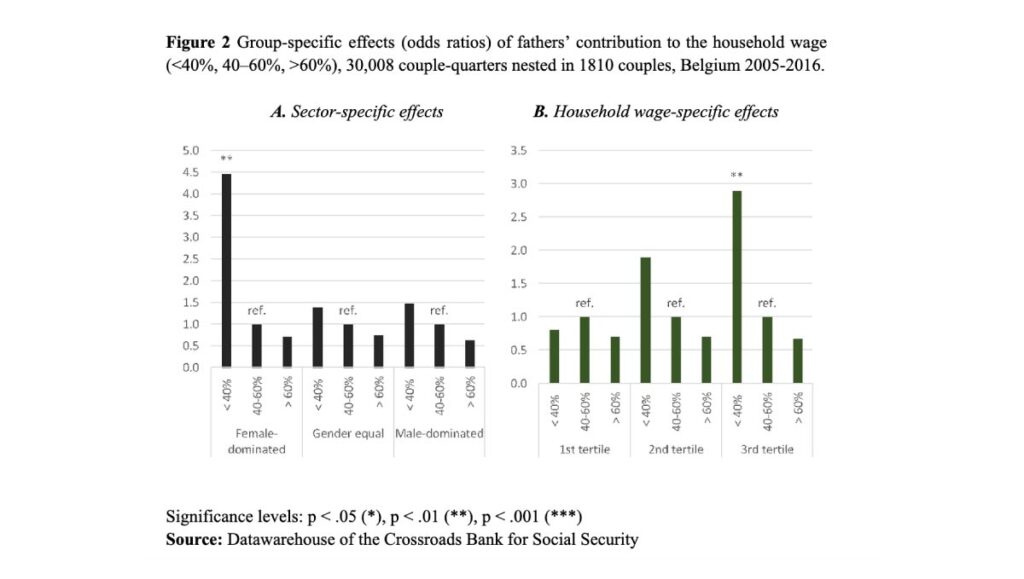

Both the quantitative and qualitative results of our study suggest that the stimulating impact of being a secondary earner on leave uptake among men is strongest among fathers in female-dominated employment sectors (Figure 2, left panel), where parental leave is depicted as more institutionalized and normalized. The positive impact of being a secondary-earning father disappears completely if he is employed in a gender equal or male-dominated workplace.

Regarding couples’ total income position, quantitative and qualitative results indicate that the occurrence and strength of the relative resources mechanism as an explanation for fathers’ leave uptake depends on the financial resources at the couple level (Figure 2, right panel). Low household income levels are seen as an important limitation on couples’ opportunities to make free decisions on parental leave uptake since leave use implies a substantial income loss. In contrast, high household income levels enhance the stimulating impact of being a secondary earner on leave uptake among men.

Finally, the qualitative results also show that limited information about parental leave schemes and gendered parenting ideals may act as potential moderators of the relative resources mechanism, a finding that warrants further attention in quantitative research. With respect to the former, considerable variation emerges in access to information about parental leave and its financial consequences, which in turn limits the degree to which relative wage positions are considered in parental leave decisions.

Gendered parenting ideals and gender role attitudes are also a moderating factor which – in case of relatively traditional views on gendered parenting roles – potentially trumps the positive impact of being a secondary earner among fathers. Unfortunately, the register data at hand did not allow us to test moderations of the relative resources mechanism in terms of limited information and gendered parenting ideals.

Cross-national variation seems to matter, yet requires further attention

The findings supporting the relative resource hypothesis in Belgium align with similar observations in Canada and Luxembourg (Marshall, 2008; Zhelyazkova and Ritschard, 2018), as well as with more commonly addressed gender patterns regarding relative wages and couples’ gendered labour force exits or changing working hours after childbirth (e.g., for Belgium: Wood et al., 2018). However, the results for Belgium diverge from previous findings for Nordic countries; parental leave uptake is notably higher among fathers when mothers and fathers earn similar wages in Norway (Lappegård, 2008; Naz, 2010) and Sweden (Marynissen et al., 2019), and no relative resources pattern is observed for fathers’ parental leave use in Finland (Lammi-Taskula, 2008). This contextual variation in the relative resources mechanism may be related to the forerunner position of Nordic countries, with highly paid and extensive earmarked leave for fathers and a commitment to gender equality as a long-standing, cross-cutting, and highly prioritized policy objective.

Conclusion

In short, secondary-earning fathers in Belgium are more likely to use parental leave than fathers with wages equal to or higher than their partner. However, relative wages only provide a limited answer to the puzzle of gender and leave taking, as primary-earning mothers are not less likely to use parental leave than their male partners. The positive association between being a secondary earner and parental leave uptake by fathers is strongest amongst men employed in female-dominated sectors of employment and couples in the highest couple wage tertile, which suggests that the stimulating effect of being a secondary earner only operates when conditions allow. Hence, the increasing prevalence of couples with a secondary-earner father will not automatically yield gender equality in parental leave uptake. This might inspire policy makers to enhance public knowledge on parental leave systems, improve workplace support for leave uptake in male-dominated sectors of employment, and address inclusiveness of leave schemes to couples with lower wages.

References

Bygren, M., & Duvander, A.-Z. (2006). Parents’ Workplace Situation and Fathers’ Parental leave Use. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(2), 363‒372.

Lammi-Taskula, J. (2008). Doing fatherhood: understanding the gendered use of parental leave in Finland [Report]. Fathering, 6, 133+.

Lappegård, T. (2008). Changing the Gender Balance in Caring: Fatherhood in the Division of Parental Leave in Norway. Population Research and Policy Review, 27, 139‒159.

Marshall, K. (2008). Fathers’ use of paid parental leave. Perspectives on Labour and Income (Statistics Canada), June 2008, 5-14.

Marynissen, L., Mussino, E., Wood, J., & Duvander, A.-Z. (2019). Parental Leave Uptake in Belgium and Sweden: Self-Evident or Subject to Employment Characteristics? Social Sciences, 8(312).

Naz, G. (2010). Usage of parental leave by fathers in Norway. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 30(5/6), 313-325. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443331011054262

Wood, J., Kil, T., & Marynissen, L. (2018). Do women’s pre-birth relative wages moderate the parenthood effect on gender inequality in working hours? Advances in Life Course Research, 36(57-69). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.04.002

Wood, J., Marynissen, L., & Van Gasse, D. (2023). When is it About the Money? Relative Wages and Fathers’ Parental Leave Decisions. Population Research and Policy Review, 42(6), 93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09837-4.

Zhelyazkova, N., & Ritschard, G. (2018). Parental Leave Take-Up of Fathers in Luxembourg. Population Research and Policy Review, 37(5), 769‒793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-018-9470-8