Disability-free grandparenthood in Italy: changes between 1998 and 2016

In Italy, grandparents are a fundamental source of care for children, and families are the main source of support for older individuals. Margherita Moretti, Elisa Cisotto and Alessandra De Rose study disability-free grandparenthood in Italy, its evolution between 1998 and 2016, and the drivers of the changes observed.

In the 20th century, Europe underwent significant demographic changes, including increased life expectancy and lower birth rates, leading to rapid population aging. Living longer means that different generations overlap for more years. However, lower and delayed fertility often result in people assuming family roles, such as grandparenthood, at older ages. As the transition to grandparenthood occurs later in life, the health status of grandparents becomes a crucial factor. Their health can strongly influence both the duration and quality of intergenerational relationships, determining whether grandparents are net providers or recipients of care (Grundy, 2005). This dynamic can affect family interactions and adult children’s outcomes, including labour force participation and fertility decisions (Moussa 2019, Rutigliano 2020). Gender differences also play a role, with women typically becoming grandparents earlier and living longer than men, but often experiencing poorer health.

Grandparents’ health in Italy

Italy is characterized by low fertility rates and high survival (Billari e Tomassini 2021), combined with a strong family-focused welfare system that emphasizes robust support networks among family members throughout life (Dykstra and Fokkema 2011). Furthermore, public care provision for children and older individuals is often inadequate, leading Italian families to rely heavily on grandparents for childcare. Conversely, grandparents themselves depend on family support when they are in need of care, often placing a significant burden on young adults, especially women.

The average age at grandparenthood in Italy increased by three years between 1998 and 2016, both for men (59 to 62) and women (54 to 57; Cisotto et al. 2022). How has this affected the evolution of disability-free grandparenthood (DFGP)?

DFGP, originally proposed by Margolis and Wright (2017), indicates the average numbers of years lived as a disability-free grandparent, and it results from the combination of three different age-specific sets of risks: mortality, disability and grandparenthood. In a recent paper (Moretti, Cisotto and De Rose 2024) we estimated DFGP for Italians aged 65 and over between 1998 and 2016, focusing on gender differences and the drivers of change.

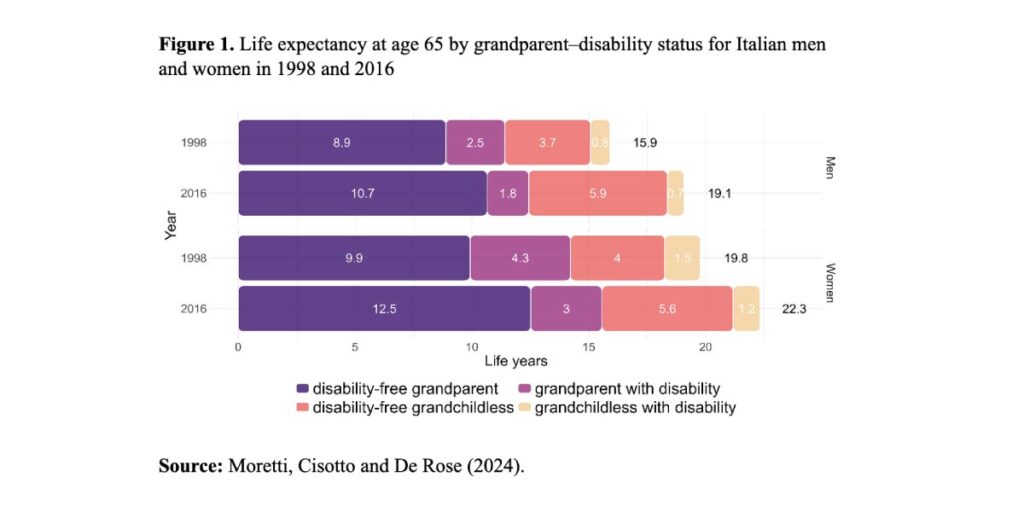

In 1998, Italian men aged 65 had a life expectancy of about 16 years, half of which were spent as healthy grandfathers. For women, the figures were about 20 years and 10 years, respectively. By 2016, life expectancy at age 65 had increased by over three years for men and by two and a half years for women. DFGP also increased to over 10 years for men and 12 years for women. In short, grandparents lived more disability-free years of overlap with their grandchildren in 2016 than 18 years before.

Despite longer life expectancy and DFGP, however, the proportion of life spent as grandparents after age 65 decreased for men, from 70% to 65%, and the gender gap in DFGP increased, with women enjoying nearly two more years of disability-free grandparenthood than men. In relative terms, in 2016, women had a higher proportion of their life expectancy at age 65 as grandmothers than men had as grandfathers (almost 70% for women and 65% for men). However, women spent a smaller share of their grandparent years free from disability (80% vs. 85% for men). Indeed, Italian women report more years of disability than men (Moretti & Strozza, 2022), both in general and in their years as grandmothers.

Drivers of changes in disability-free grandparenthood

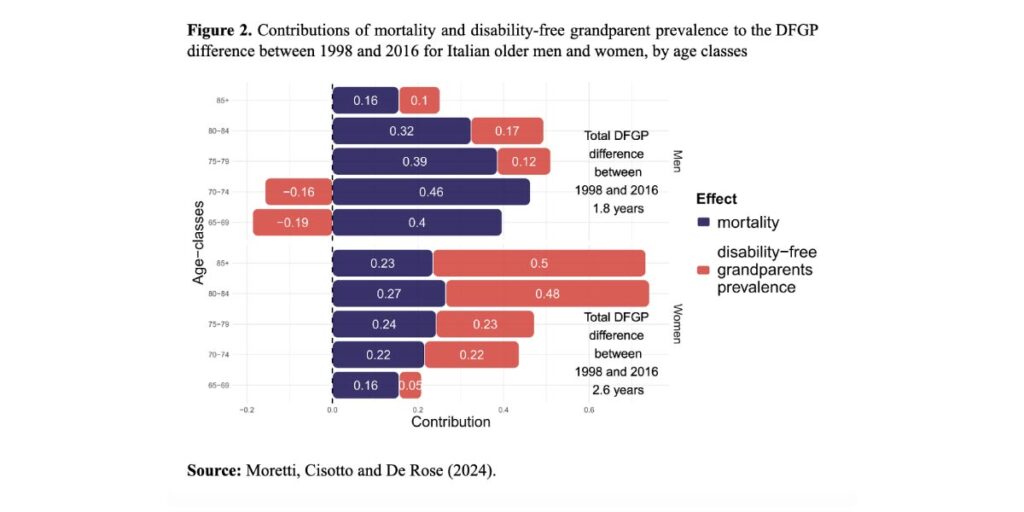

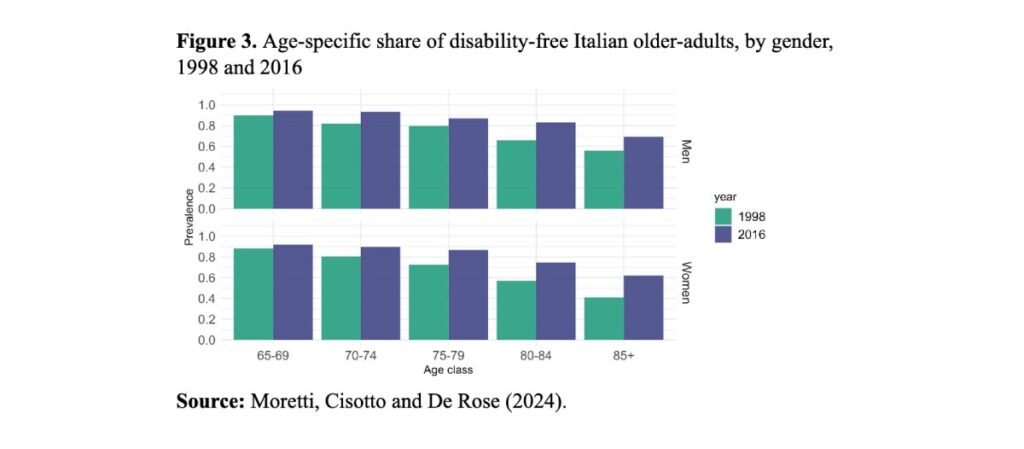

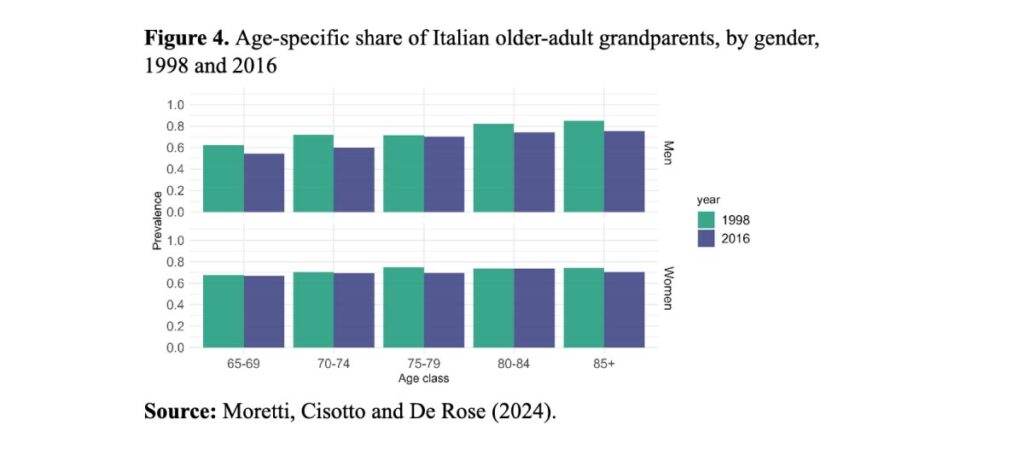

Improvements in health and longer survival were the main reasons for increased DFGP over time (Figure 2). For men, however, the decrease in the prevalence of grandparents at younger ages, due to reduced and delayed grandparenthood, slowed the increase in grandparenthood years, and this is reflected in the smaller increase in disability-free grandparent years. For women, at younger ages (65 to 79), reduced mortality was the main reason for the increase in DFGP. At older ages, improvements in population health (lower disability prevalence) and a relatively constant prevalence of grandmothers were the most important factors. For men, instead, the changes in DFGP are explained almost totally by the lengthening of life. The decrease in the prevalence of grandfathers at younger ages (65 to 74), partially offsets the gains from reduced mortality and disability risks over the three decades (Figures 3 and 4).

Conclusions

These findings highlight the complex interplay between the factors that determine the evolution of healthy grandparenthood. They also show that policies aimed at improving the health and well-being of older adults also affect others, their relatives in particular, by modifying the likelihood that older family members will be net providers or receivers of care.

References

Billari, F.C. and Tomassini, C. (2021). Rapporto sulla popolazione: L’Italia e le sfide della demografia. Bologna: Società editrice il Mulino, Spa.

Cisotto, E., Meli, E., and Cavrini, G. (2022). Grandparents in Italy: Trends and changes in the demography of grandparenthood from 1998 to 2016. Genus 78(1): 10. doi:10.1186/s41118-022-00153-x.

Dykstra, P.A. and Fokkema, T. (2011). Relationships between parents and their adult children: A West European typology of late-life families. Ageing and Society 31(4): 545–569. doi:10.1017/S0144686X10001108.

Grundy, E. (2005). Reciprocity in relationships: Socio-economic and health influences on intergenerational exchanges between Third Age parents and their adult children in Great Britain. The British Journal of Sociology 56(2): 233–255. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2005.00057.x.

Margolis, R. and Wright, L. (2017). Healthy grandparenthood: How long is it, and how has it changed? Demography 54(6): 2073–2099. doi:10.1007/s13524-017-0620-0.

Moretti, M., Cisotto, E., & De Rose, A. (2024). Uncovering disability-free grandparenthood in Italy between 1998 and 2016 using gender-specific decomposition. Demographic Research, 50, 1247–1264.

Moretti, M. and Strozza, C. (2022). Gender and educational inequalities in disability-free life expectancy among older adults living in Italian regions. Demographic Research 47(29): 919–934. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2022.47.2

Moussa, M.M. (2019). The relationship between elder care-giving and labour force participation in the context of policies addressing population ageing: A review of empirical studies published between 2006 and 2016. Ageing and Society 39(6):1281–1310. doi:10.1017/S0144686X18000053.

Rutigliano, R. (2020). Counting on potential grandparents? Adult children’s entry into parenthood across European countries. Demography 57(4): 1393–1414. doi:10.1007/s13524-020-00890-8.