Challenging claims of disadvantage in same-sex parented families, Jan Kabátek and Francisco Perales find that same-sex-parented children actually outperform their peers in many areas of academic achievement.

Over the last 50 years, there have been dramatic changes in social attitudes and legislation toward same-sex relationships (Roseneil et al 2013). Within this short time frame, many countries have moved from criminalization to robust institutional support – enabling same-sex couples to be formally recognized, marry, and adopt children. Despite these developments, same-sex parenting remains a highly controversial and politicized issue, and one that is tightly intertwined with discussions around same-sex marriage.

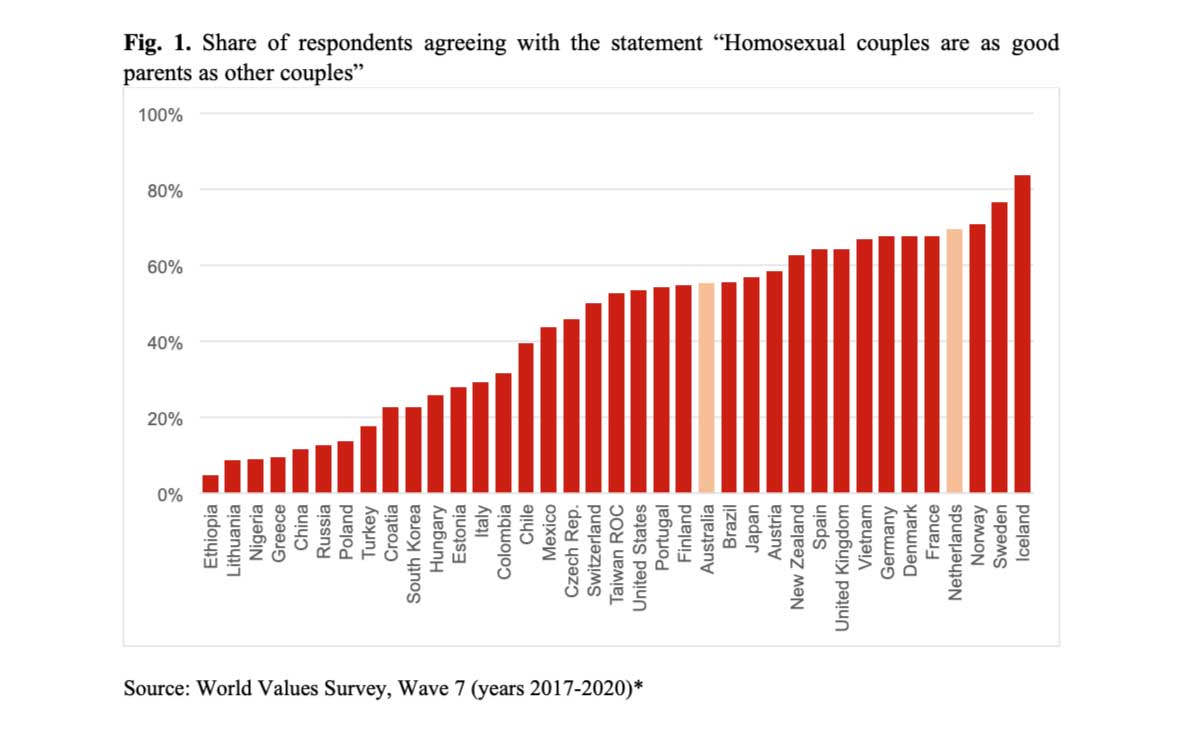

Data from the most recent wave of the World Values Survey, a large cross-national survey of public opinion, confirms that support for same-sex parenting is far from unanimous. A sizable share of the population across multiple countries still believes that same-sex parents cannot raise children as well as different-sex parents (Figure 1).

These beliefs are often bolstered by “common wisdom” arguments that are rarely backed up by robust empirical evidence. For example, some commentators maintain that children need both male and female parental role models to thrive, that non-biological parents invest less effort in parenting their children, and that children in same-sex-parented families may be subjected to shame and bullying.

However, these beliefs have also been fueled by questionable academic studies examining the comparative outcomes of these children.

Prior research

Mark Regnerus’s, a sociologist and professor at the University of Texas at Austin conducted a controversial study in 2012 that serves as a cautionary tale about the negative and far-reaching consequences that poor data and unsuitable analytical methods can exert on research findings in this field.

The Regnerus (2012) study claimed that people raised by same-sex parents experienced worse health and socioeconomic outcomes in adulthood than people raised by different-sex parents. Yet subsequent re-analyses of the same data by several leading researchers demonstrated that such associations emerged almost entirely due to an array of misclassification, mismeasurement and other analytic problems (Cheng and Powell 2015, Rosenfeld 2015).

The damage of the Regnerus study was however done, with its spurious findings receiving intense international media coverage and becoming a ‘go-to’ resource for activist groups lobbying against same-sex marriage. Such findings not only permeated the public debate on same-sex parenting, but were also presented in court in attempts to prevent the introduction of same-sex marriage legislation across US states.

Nevertheless, the Regnerus study constitutes an outlier in the broader literature on same-sex parenting. A large majority of studies on the topic have found that same-sex parents are able to provide their children with as healthy and nurturing home environments as different-sex parents. Yet these studies have also been often called into question, with critics pointing out that they are typically based on suboptimal data and methods (Allen 2015).

The most common criticism is that the studies tend to rely on ‘convenience’ samples. These are small and selective samples of same-sex-parented families, who may be approached at LGBT events or recruited through mailing campaigns. Critics (rightfully) argue that the outcomes of such families may differ from those of the broader population of same-sex families, and that this can distort the reliability of the studies and their conclusions.

Our new study

In our study, we were able to move beyond the vast majority of research conducted in this space. We did this by analyzing data covering the full population of children living in the Netherlands (more than 1.4 million children in total), comparing the academic outcomes of all children raised by same-sex couples with all children raised by different-sex couples. We conducted the study in the Netherlands because it is one of only a few countries in the world that allows researchers to link together life-long anonymized data from multiple population registers, containing high-quality administrative information on children and their families (Kabátek and Ribar 2020).

Thanks to these data, we were able to statistically account for various pre-existing characteristics that may differ between same-sex- and different-sex-parented families—for example, the higher average education attainment of individuals in same-sex couples, or their lower average incomes. This means that our analyses compared children in same-sex- and different-sex-parented families that are similar in all observable characteristics except for their parents’ sex.

Our key findings go counter to those reported by Regnerus (2012). Children in same-sex-parented families attain higher scores on national standardized tests than children in different-sex-parented families. Their advantage amounts to 13 per cent of a standard deviation, which is comparable to the advantage associated with both parents being employed as opposed to being out of work. We also find that children in same-sex-parented families are slightly more likely (1.5 per cent) to graduate from high school, and much more likely (11.2 per cent) to enroll in college than children in different-sex-parented families.

Our results thus challenge “common wisdom” arguments against same-sex parenting, and lend preliminary support to other scholarly perspectives that emphasize the possible benefits of same-sex parenthood. For example, same-sex parents are likely to face substantive barriers to parenthood (including social scrutiny, greater costs of conceiving a child, and legislative hurdles) and overcoming these barriers may strengthen their commitment to parental roles. Combined with the fact that same-sex couples face minimal odds of becoming parents through ‘accidental’ pregnancies, this can result in more positive parenting practices in same-sex-parented families.

Implications for other countries

The Netherlands features high levels of public approval of same-sex relations and provides robust legislative protection to sexual minorities. Therefore, we argue that the Dutch institutional context represents a ‘best-case scenario’ concerning the achievement of children in same-sex-parented families.

Same-sex-parented families in other countries may be subject to environmental hurdles that remain beyond the control of parents and that may negatively affect their children. These may include a lack of access to the social institution of marriage and more profound experiences of stigma and discrimination (Perales and Todd 2018).

By undertaking our analyses in the Netherlands, we were able to retrieve findings that are more likely to reflect the influence of same-sex parenting itself, and less likely to reflect external influences stemming from non-inclusive institutional environments. Therefore, our findings portray a viable scenario of what could happen in countries with more restrictive institutional environments, should they direct comparable efforts towards the inclusion of sexual minorities.

Altogether, the message stemming from our findings is clear: being raised by same-sex parents bears no independent detrimental effect on children’s outcomes. In socio-political environments that provide high levels of legislative and public support, children in same-sex-parented families thrive.

*Source figure 1 – worldvaluessurvey.org

References

Allen Doug (2015) More Heat Than Light: A Critical Assessment of the Same-Sex Parenting Literature, 1995–2013, Marriage & Family Review, 51(2): 154-182. doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2015.1033317

Cheng Simon, Powell Brian (2015) Measurement, methods, and divergent patterns: Reassessing the effects of same-sex parents. Social Science Research, 52, July, 615-626. DOI: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.04.005.

Kabátek Jan, Perales Francisco (2021) Academic Achievement of Children in Same- and Different-Sex-Parented Families: A Population-Level Analysis of Linked Administrative Data From the Netherlands. Demography. doi.org/10.1215/00703370-8994569

Kabátek Jan, Ribar David C (2020) Daughters and Divorce. The Economic Journal, December. doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueaa140

Perales Francisco, Todd Abram (2018) Structural stigma and the health and wellbeing of Australian LGB populations: Exploiting geographic variation in the results of the 2017 same-sex marriage plebiscite. Social Science & Medicine, 208: 190-199. doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.015

Regnerus Mark (2012) How different are the adult children of parents who have same-sex relationships? Findings from the New Family Structures Study. Social Science Research, 41(4): 752-770.

Roseneil Sasha, Crowhurst Isabel, Hellesund Tone, Santos Ana Cristina, Stoilova Mariya (2013) Changing Landscapes of Heteronormativity: The Regulation and Normalization of Same-Sex Sexualities in Europe. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 20(2): 165–199. doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxt006

Rosenfeld Michael J. (2015) Revisiting the Data from the New Family Structure Study: Taking Family Instability into Account. Sociological Science, September, DOI 10.15195/v2.a23.