Are grandchildren beneficial to mental health in old age? Using advanced statistical techniques and data from 160,000 individuals across Europe, Elisa Brini and Francesca Zanasi challenge this common belief: family ties do not significantly reduce the risk of depression for men and women in later life.

Why should family ties influence mental health?

With population ageing and declining fertility rates, there is growing concern about childless older adults, who are considered more vulnerable to social isolation as they leave the workforce and face reduced independence – factors linked to mental health risks.

An extensive review of the existing literature reveals two relevant but scarcely overlapping research streams. The former examines the mental health consequences of childlessness in later life, typically comparing childless older adults with parents, but often overlooking the fact that many parents are also grandparents. The latter focuses instead on grandparenthood, comparing older individuals with or without grandchildren, while excluding childless individuals altogether. This gap in the literature has limited our understanding of the role family status plays in mental health in old age, and scientific research has yet to reach a consensus on whether ageing without children or grandchildren affects mental health, in what sense and by how much.

Family ties are often viewed as vital for emotional support and social connections. Relationships with children are important in later life: close and supportive ties can enhance psychological well-being, while conflictual relationships may have the opposite effect. Additionally, family members often exchange time and resources, with adult children providing care for elderly parents, and parents offering financial support or care to grandchildren. Being a grandparent may also provide a sense of purpose and fulfilment. Nevertheless, studies show that childless individuals often compensate for the lack of family ties with other support networks, including relatives, friends, and volunteer activities.

Three insights for studying family ties in later life

In a recent study (Brini & Zanasi 2024), we introduced three innovative approaches to understanding the relationship between family ties and mental health in later life.

First, we differentiated between three (not just two) categories of older adults: people without children, parents without grandchildren, and grandparents, thus providing a more nuanced range of family situations and ties than the traditional dichotomous classifications mentioned earlier.

Second, we adopted a life-course approach, because family ties may affect well-being differently at different ages (Elder et al. 2003). This approach also highlights the role of social expectations relative to the normative timing of transitions (Furstenberg, 2005) that shape the perception of these transitions – whether as “early”, “on-time”, or “late” – and influence self-image. For instance, becoming a grandparent at a young age may exacerbate depressive symptoms by intensifying feelings of ageing, while becoming a grandparent at a socially expected age may boost self-esteem and help protect against depression. The timing of transitions also brings attention to situations of role overlap and competing obligations (Leopold & Skopek, 2015). Younger grandparents may experience stress from juggling work, grandchild care, and caregiving duties toward both adult children and ageing parents, and this may diminish the psychological benefits of grandparenthood. Conversely, older grandparents, often retired, face fewer overlapping roles and can better enjoy the experience of having grandchildren.

Third, we used advanced statistical models to control for selection effects – factors influencing both future family status and psychological well-being over the life course. This approach ensures reliable estimates of the causal effects of family ties on mental health.

Data and methods

We analysed data from eight waves of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), conducted between 2004 and 2020, covering 17 European countries. Mental health is measured using the Euro-D scale for depressive symptoms. We categorized individuals into three family status groups: childless adults, parents without grandchildren (grandchildless), and grandparents. To examine the relationship between family status and mental health, we used Inverse Probability Weighted Regression Adjustment (IPWRA) (Petersen et al., 2006). This approach makes the groups comparable by weighting observations based on the likelihood of having a particular family status given a set of confounding characteristics, and thus ensures a reliable estimate of the Average Treatment Effect (ATE).

Results

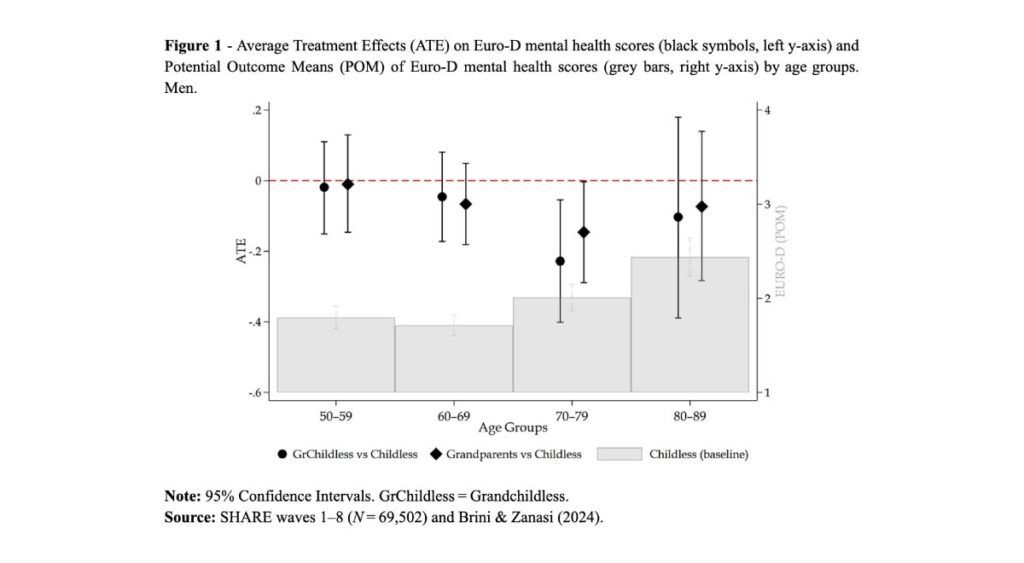

Our findings (Figure 1) show that depressive symptoms (Euro-D scores) increase with age for men. Among men aged 50–59, childless individuals (grey bars) report an average of almost 2 depressive symptoms, rising to 2.5 symptoms at ages 80–89. However, no significant differences are observed between grandchildless men (black circles) and grandfathers (black diamonds), except for men aged 70–79, where the grandchildless report 0.22 fewer symptoms and grandfathers 0.14 fewer symptoms than childless men. The results for women, not reported here, mirror these findings, with no significant differences across any age group.

Beyond family: broader determinants of well-being

The results from our analyses reveal no clear psychological advantage to being a grandparent compared to being a parent without grandchildren or being childless, across all age groups and for both genders, with the exception of men aged 70–79, among whom fathers (with or without grandchildren) perform slightly better than childless men, in terms of mental health.

These findings seem to suggest that psychological well-being in later life is more influenced by life experiences and socioeconomic conditions than by family status. Therefore, public policies addressing demographic challenges must go beyond traditional family structures, promoting healthy lifestyles, social support, and economic resources from early life, regardless of family composition.

References

Brini, E., & Zanasi, F. (2024). (Grand) childlessness and depression across men and women’s stages of later life. Journal of Family Studies, 30(3), 365-396. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2023.2230970

Elder, G. H., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course. Handbooks of sociology and social research (pp. 3–19). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1

Furstenberg, F. F. (2005). Non-normative life course transitions: Reflections on the significance of demographic events on lives. Advances in Life Course Research, 10, 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-2608(05)10005-7

Leopold, T., & Skopek, J. (2015). The demography of grandparenthood: An international profile. Social Forces, 94(2), 801–832. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sov066