Labour force participation among older adults in India

India’s economic sector faces a reckoning with its ageing population. Aparajita Chattopadhyay and David E. Bloom‘s analysis, based on the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI), indicates that health is the main determinant of working into old age, making healthy aging a priority for the future of the country.

India’s population is getting older. Adults aged 60 years and above will outnumber children under 10 years of age by 2030, and will likely reach some 340 million (about 20% of the population) by 2050. India must therefore start to face the economic and health issues that accompany population ageing: among these, monitoring and possibly increasing labour market participation at mature ages. Unfortunately, until recently, due to the paucity of nationally representative data for the 60+ population, little was known about the work characteristics and the determinants of work among older adults in India: only that it is mainly in the informal labour market, with low social security coverage and low female participation.

Work characteristics of older adults in India

To learn more about this population subgroup, the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) was launched in 2017, interviewing over 73,000 respondents aged 45 and above, and their spouses regardless of age. Questions were asked about health, healthcare access and utilization, work status, family and social support, social insurance coverage, retirement pension, and economic situation across 36 states and union territories of India (IIPS 2020). In a recently published paper, we analysed these data (except for the State of Sikkim), and found several interesting results (Chattopadhyay et al., 2022). For instance, only some 36% of older adults (here defined as those aged 60 years and over) are engaged in income-generating activities (50% if they are men), 38% have worked in the past but then stopped, and the remaining 26% have never worked (almost 50% if they are women).

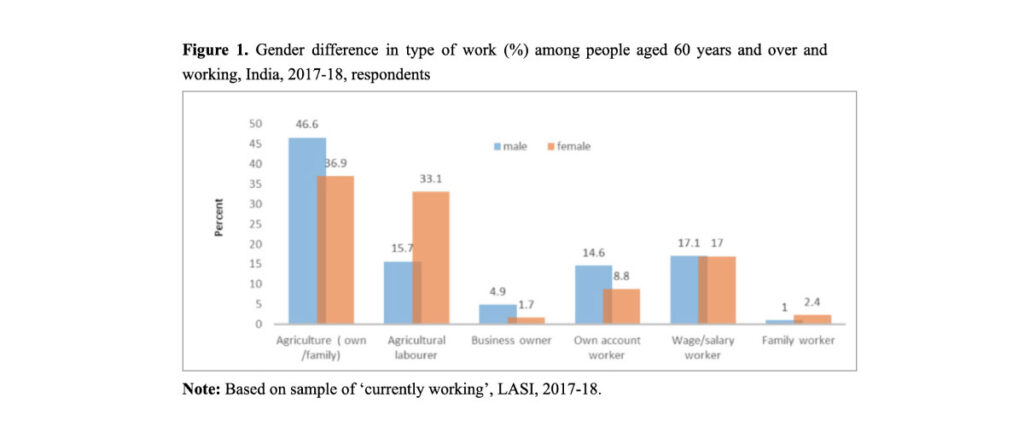

Among older adults who are working, a mere 5% have full-time jobs, and only 25% have documentary evidence of their current work, indicating a predominance of the informal sector in the Indian economy. Approximately 33% of older women are agricultural labourers, as opposed to 16% of older men, while in all the types of work that indicate “ownership of wealth” (i.e., farm owner, own business, own-account worker), men prevail (Figure 1) (Chattopadhyay et al., 2022).

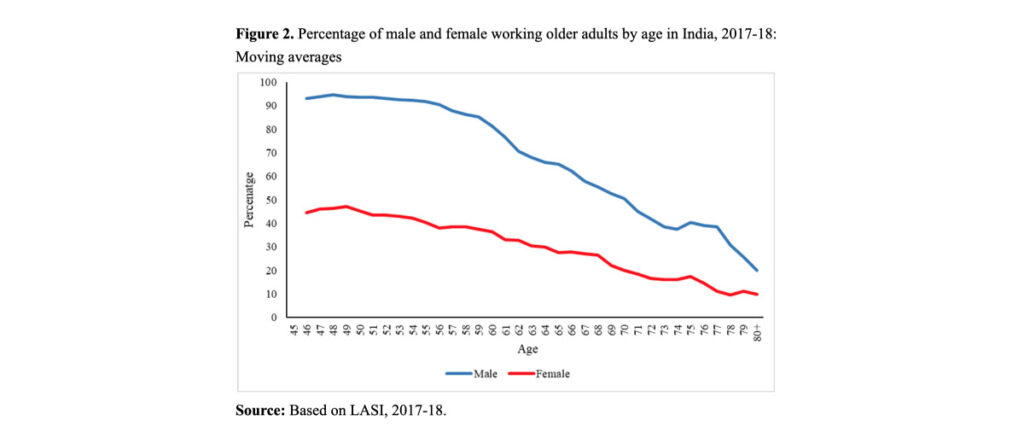

Pension coverage is rare: it benefits only about 12% of older men and 3% of older women, among those who are working or worked previously. Contrary to the popular belief that workforce participation starts to decline beyond age 60, LASI data reveal that this happens much earlier in India, especially for women (Figure 2).

Gender, wealth, education, and work

In India, women are less likely to work than men, in part for health reasons (Chattopadhyay & Roy, 2005) but most importantly because they are traditionally in charge of household chores. Contrary to expectations, female work participation is lower among educated women and in urban areas: this may indicate lack of opportunities (Vyas, 2020), mismatch between workers’ skills and job requirements, and increased family (female) responsibilities in urban areas, where support from kin and neighbours is rarer.

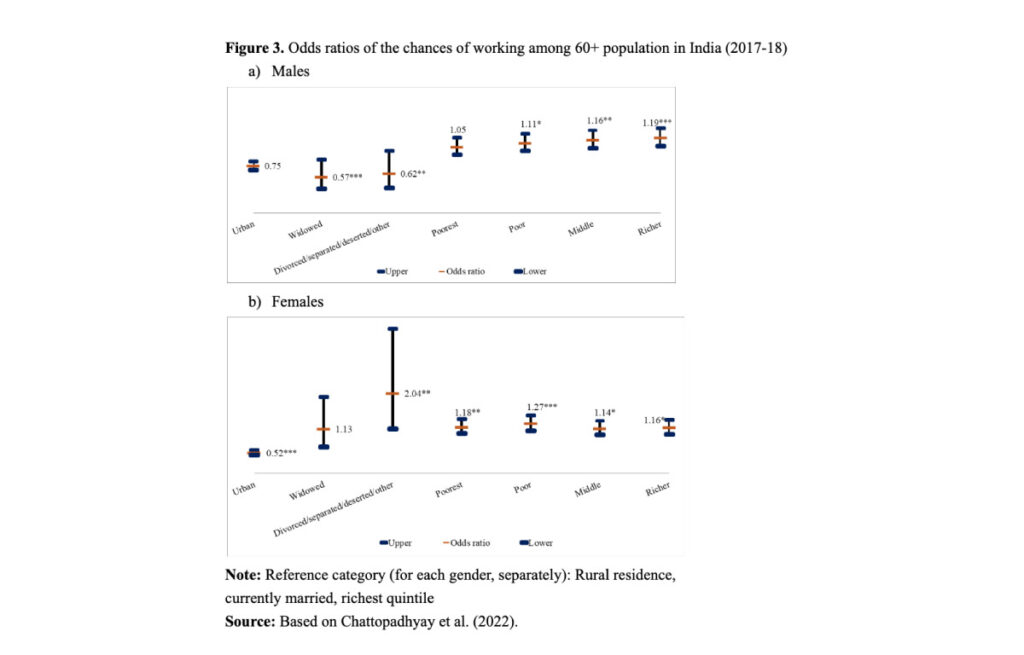

However, poor, rural, and divorced/separated/deserted older women are significantly more likely to work than men in similar conditions, evidently because their economic conditions are less favourable (Figure 3).

Labour force participation among Indian older adults is lowest among the richest and the poorest, but for different reasons. The former, mainly engaged in white collar, well-paid jobs in their adult years, benefit from better pension/health insurance coverage and do not need to work. The latter, instead, must frequently stop working because of poor health.

Family, residence, health and work

Older adults who live with their (adult) children are less likely to work beyond age 60. This is largely because they are either in need of care from close kin or, if they are healthy, they provide care themselves, to their grandchildren: about 25% provide childcare, as compared to a mere 10% of older adults who do not live with their children (IIPS, 2020).

In general, rural older adults are more likely to work than their urban counterparts (Figure 3), due in part to the opportunity to engage in farming and allied activities, and in part to the lack of social security benefits, as their past earnings were low and insufficient to generate significant savings or pension contributions.

Health is a stronger predictor of work status in rural than in urban areas. Rural older adults with chronic ailments are 43% less likely to work than their healthy rural counterparts, whereas urban older adults with chronic ailments are “only” 31% less likely to work than their healthy urban counterparts. This may be due to the rural population’s limited access to health facilities, resulting in untreated ailments that prevent older adults from engaging in agricultural and other labour-intensive work. In urban settings, better access to health services and medication may lessen the effect of health on work participation at older ages (Jana & Chattopadhyay, 2022).

Conclusions

A key question when considering older adult employment in India is whether work in old age indicates deprivation. The answer is mixed. The affirmative response corresponds to the engagement of older Indian adults in part-time jobs, in agriculture and in the informal sector with relatively lower income. In addition, with educational attainment, familial support, and better social security coverage, people are generally less likely to work in old age, indicating that financial insecurity may be the reason why Indian older adults continue to work.

However, it should also be noted that healthy older Indians are likely to work beyond the age of 60, possibly indicating a desire to remain active in the labour market.

Elder employment has positive effects on youth employment, on the wellbeing of older workers, and on economies and societies in multiplicative ways (Jasmin & Rahman, 2021). This practice is in tune with the healthy and active aging initiative promoted by the World Health Organization, and it should therefore be encouraged. India’s 1999 National Policy for Older Persons made positive steps in this direction, but the time has probably come to renew and relaunch that programme.

Acknowledgements

We thank Arunika Agarwal, Research Associate, Harvard T.H Chan School of Public health and Priya Maurya, PhD scholar of IIPS for their useful comments, and the funders of the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI), i.e. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India and National Institute on Aging, US.

References

Chattopadhyay, A., Khan, J., Bloom, D. E., Sinha, D., Nayak, I., Gupta, S., Lee, J., & Perianayagam, A. (2022). Insights into Labor Force Participation among Older Adults: Evidence from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India. Journal of Population Ageing, 15(1), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-022-09357-7

Chattopadhyay, A., & Roy, T. K. (2005). Does retirement affect healthy ageing? A study of two groups of pensioners in Mumbai, India. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 20(1), 89–115. https://doi.org/10.18356/0ef4333e-en

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), National Programme for, Health Care of Elderly (NPHCE), MoHFW, & Public Health (HSPH) and the University of Southern California (USC). (2020). Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017-18, India Report. International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai. https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/lasi/

Jana, A., & Chattopadhyay, A. (2022). Prevalence and potential determinants of chronic disease among elderly in India: Rural-urban perspectives. PLOS ONE, 17(3), e0264937. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264937

Jasmin, A. F., & Abdur Rahman, A. (2021). Does Elderly Employment Reduce Job Opportunities for Youth? [Brief]. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36170

Vyas, M. (2020). Impact of Lockdown on Labour in India. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63(1), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00259-w