Earning their keep? Fostering, education and work in Tanzania

Fostering is common throughout sub-Saharan Africa, but the motivations for fostering and consequences for fostered children remain unclear. In northern Tanzania, Sophie Hedges, Rebecca Sear, Jim Todd, Mark Urassa, and David W. Lawson find

that fostered children suffer minimal educational disadvantages, even when orphaned, and argue that strong family networks and children’s work contributions make fostering beneficial for foster carers and children alike.

The pros and cons of fostering in sub-Saharan Africa

The Ga people in Ghana believe that parents spoil and pamper their children, and that children should be sent to live with other families in order to be properly brought up. Among Xhosa families in South Africa, the first child is frequently brought up by their maternal grandmother so that a young mother can observe and gain experience in childrearing. In Sierra Leone, Mende parents might send their children to live with wealthier or more influential families to make important political links. In fact, in many societies in sub-Saharan Africa children’s upbringing is the responsibility of their wider family and community, and children may frequently live away from their parents in foster families, generally with close relatives. These arrangements are often flexible, with children moving back and forth between households, and may be made for a variety of reasons: to help an elderly grandparent with chores or farm work, to live with a favourite relative, to relieve the burden on a struggling family, or to be closer to school.

This contrasts strongly with perceptions of fostering in higher-income countries, where it is viewed as a last resort, to be used only in cases of neglect, abuse, or the death of a child’s parent. International development programmes often highlight the situation of children fostered as a result of orphanhood, with these children classed as ‘vulnerable’ and in need of help (Tatek 2012). This view of fostering is borne out by many studies in lower and middle income countries on the consequences of fostering for children, which have found that fostered children are less likely to go to school, and that they have to work hard to ‘earn their keep’. Yet if fostering is bad for children, why is it so common?

The answer is likely that fostering outcomes are very context-dependent. In Malawi, fostering has not traditionally been part of childhood, and children fostered after the death of a parent from HIV are much less likely to be in school. By contrast, Ghana has a long history of fostering, and here fostered children are no less likely to attend school than children living with their parents (Hampshire et al 2015). Who fosters children is also important – several studies show that children living with their grandparents are no worse off than those living with their parents, but that living with more distant relatives can have a negative impact on children’s education.

Fostering and education in Tanzania

In north-western Tanzania, fostering was traditionally very common, and children’s living arrangements were flexible; children could choose where to live, or relatives might request to foster children in order to have help with farm work or chores. However, the HIV epidemic has led to an increase in the number of orphans, potentially stretching these traditional arrangements. This is therefore an interesting context in which to look at the effects of fostering on children’s education and work.

In a recent study (Hedges et al 2019) we collected data on the living arrangements, school enrolment, and time allocation of 1,273 children and young people aged between 7 and 19 from two villages in the Mwanza region of north-western Tanzania (Map. 1).

Around a quarter of children in our sample were fostered; among these children, the majority are not orphans, and two-thirds live with close relatives (mainly grandparents). We hypothesised that fostered children might be disadvantaged in their education, and that they would have to work harder than children living with their parents in order to ‘earn their keep’. Additionally, we thought that among fostered children, orphans would be particularly disadvantaged because they do not have their parents available to step in and protect them or provide additional support.

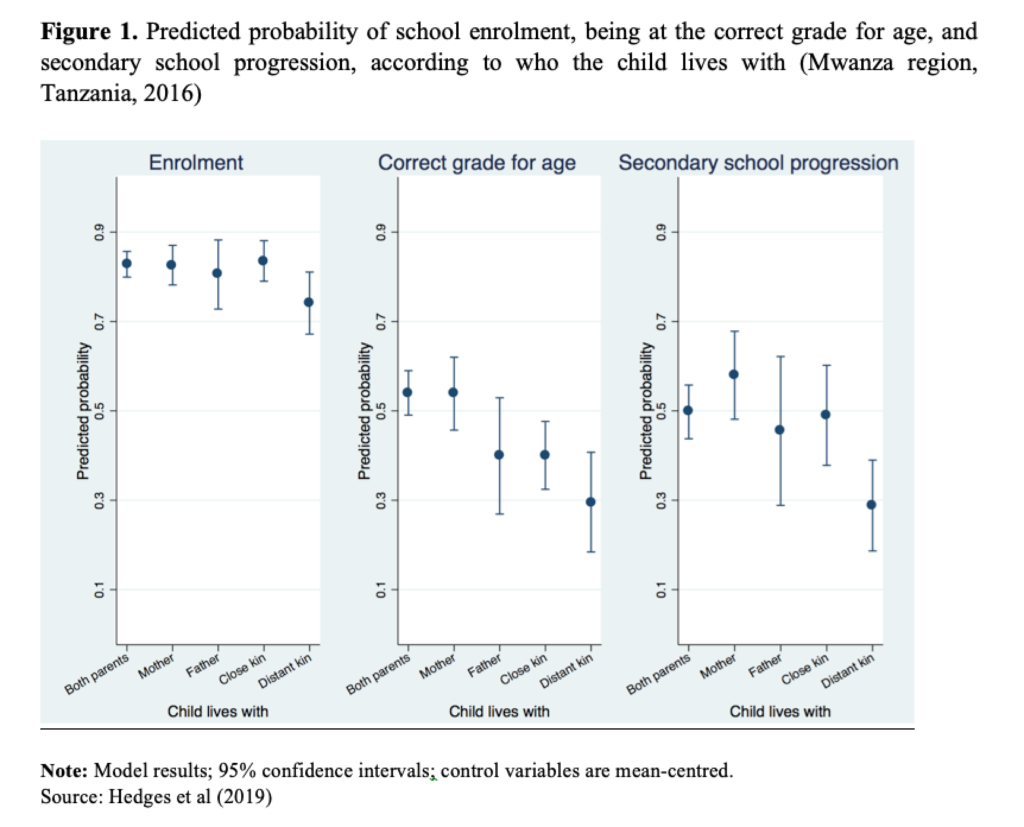

In fact, we see little difference in education between children living with their parents, and children living with close relatives (Figure 1). The only difference is that the latter are less likely to be at the correct grade for age, which might reflect a disruption to their studies connected to being fostered. Those fostered by distant kin, however, are less likely to be enrolled, and less likely to go to secondary school. This might suggest that distantly-related foster families do not invest as much in foster children’s education. The association might also be in the opposite direction, in that children might be fostered by distant kin – who tend to live further from their parents than close relatives – because they don’t want to go to school; anecdotally we heard of teenagers running away from home because they had argued with their parents about attending school. We did not find any indication that orphans were any worse off than other foster children.

Fostering and children’s work

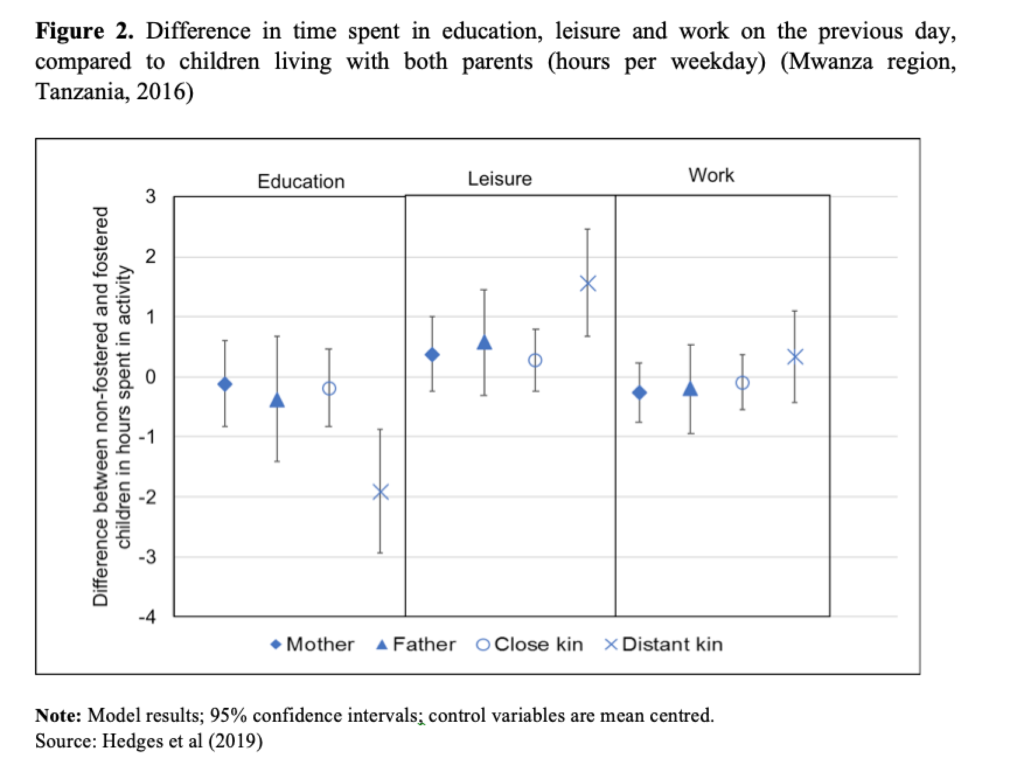

In terms of children’s work, we find that fostered children are more likely to report doing farm work during the past week, suggesting that they might have been fostered in order to help out with farming. But looking at time allocation on weekdays, when work would potentially conflict with schooling, we find that those living with close relatives are no different to those living with parents. In Figure 2, we can see that children living with just their mother, just their father, or close kin, do not differ from children living with both parents in their time spent in education, leisure or work. Children living with distant relatives do a little more work than non-fostered children, but the main difference is actually that they have a lot more leisure time (nearly two hours more), and spend less time in school. This suggests that being made to work is unlikely to be the reason behind their lower school enrolment.

In the Mwanza region we find that fostering is common, and that when children live with close relatives, predominantly their grandparents, their education does not seem to suffer, though they may do more farm work at weekends. Flexible living arrangements and circulation of children between families has traditionally been important in this region, with great reliance on extended family networks to help distribute the costs of raising children, and to help meet the labour demands associated with small-scale farming. These networks also seem very effective in buffering orphans from the effects of parental loss, with no indication that orphans are any worse off than other fostered children.

This contrasts with the portrayal of orphans in sub-Saharan Africa in the international media as inherently vulnerable and lacking resources and support. While it is important to identify and support children who genuinely lack care and support, this broad-brushed approach fails to recognise the social capital that many orphans have in the form of strong family networks and community responsibility for fostering children – both in the sense of providing a roof over their head, but also in the sense of encouraging their development and education.

References

Hampshire Kate, Porter Gina, Agblorti Samuel, Robson Elsbeth, Munthali Alister, Abane Albert (2015) Context matters: fostering, orphanhood and schooling in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Biosocial Science, 47(2):141-164.

Hedges Sophie, Sear Rebecca, Todd Jim, Urassa Mark, Lawson David W. (2019) Earning their keep? Fostering, children’s education, and work in north-western Tanzania. Demographic Research, (41-10): 263–292.

Tatek Abebe (2012) AIDS-affected children, family collectives and the social dynamics of care in Ethiopia. Geoforum, 43(3):540-550.