Does childrearing affect women’s economic opportunities?

As fertility declines in low- and middle-income countries, the time women devote to childrearing may also be reduced, opening up possibilities for women to pursue educational and employment opportunities. John Bongaarts, Ann K. Blanc and Katharine McCarthy analyze data from 58 low- and middle-income countries and show that the more children women have living at home, the less likely they are to be employed.

Would improving women’s ability to control their reproductive lives in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) positively transform the global economy, or at the very least boost women’s economic empowerment?

The intuitive answer from any working mother is likely to be a resounding “yes,” and there is indeed evidence from high-income countries showing that as fertility declines, women are able to pursue educational and employment opportunities previously constrained by the demands of bearing and raising children. However, the answer to this long-pursued question is less clear for low- and middle-income countries where potentially large-scale implications for investments in health and development programs exist (Lee and Finlay 2017). Economic growth and development are enhanced if all members of the working-age population can contribute their potential.

We investigated the relationship between women’s employment (work for cash or in-kind payment) and assessed its relationship with the number of children living with them at home, using DHS survey data from 58 low- and middle-income countries (Bongaarts et al. 2019).

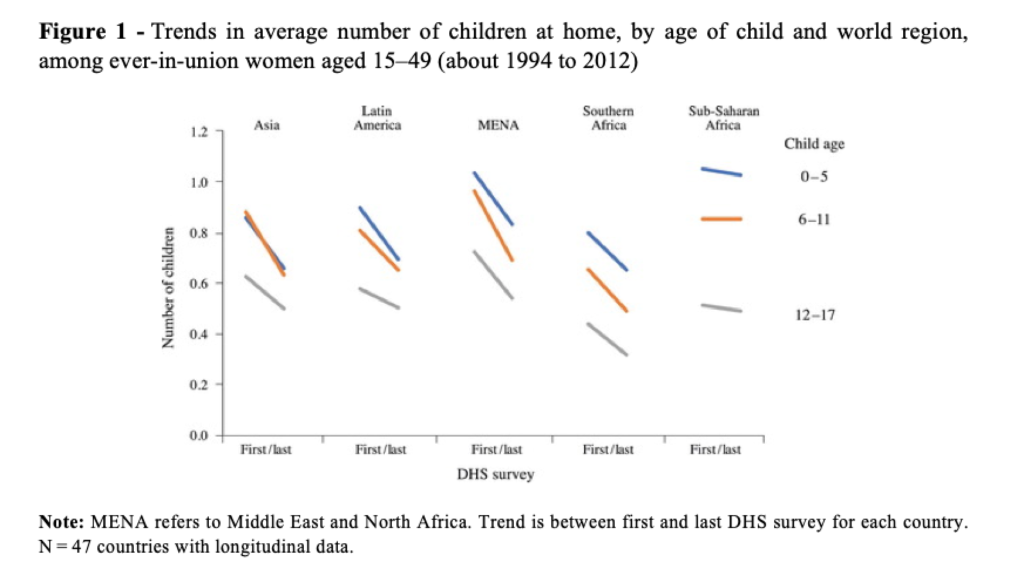

The findings show that, across these countries, the average number of children that women have living at home has declined in all regions of the developing world over the last few decades, although there has been the least amount of change in sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 1). We examined Southern Africa separately from the rest of sub-Saharan Africa due to its distinctively low levels of co-residence of children with their mothers. These downward trends are consistent with fertility declines throughout much of the developing world in recent decades.

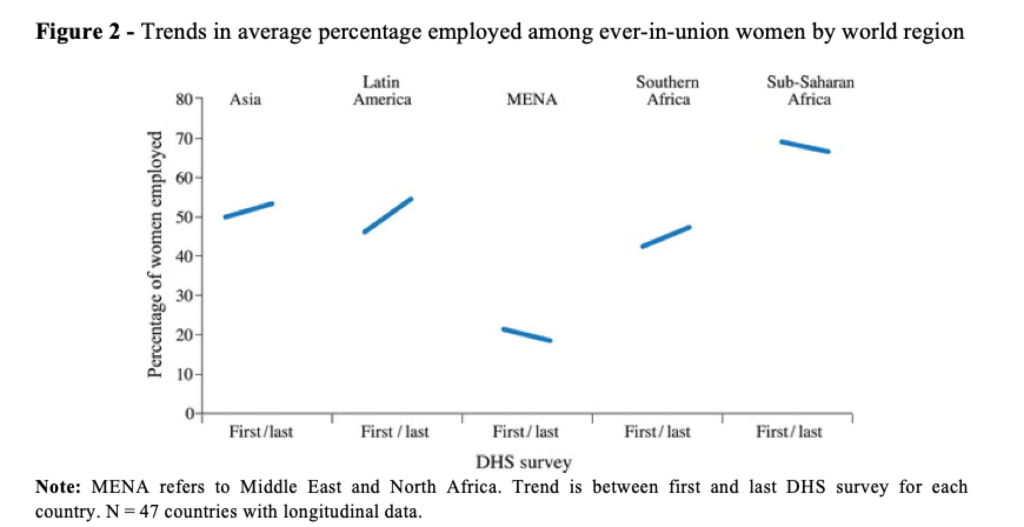

Over the same period (roughly 1994-2012), female employment rates changed relatively little, but large and persistent regional differences exist (Figure 2). The lowest levels of female employment are seen in the Middle-East/North Africa while the highest are in sub-Saharan Africa.

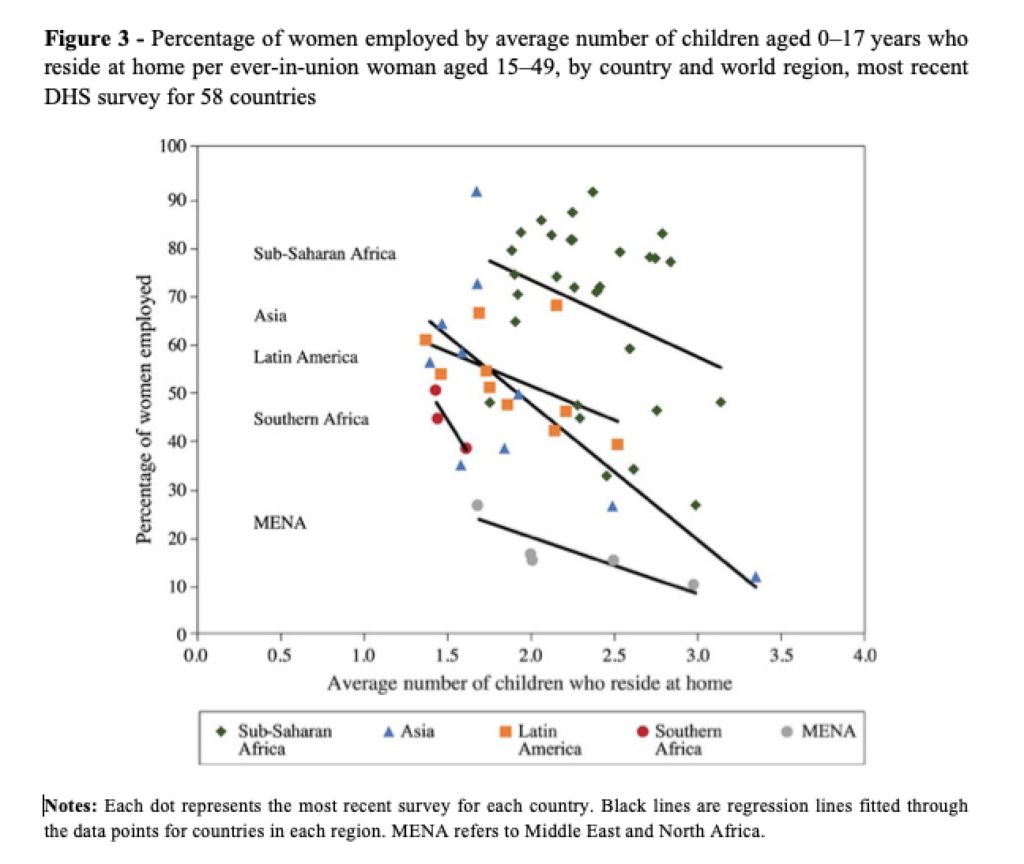

More children at home = less employment for women

The study found a consistent negative association between women’s employment and having children at home, meaning that across all regions, the more children women have at home the less likely they are to be employed. In fact, for every one additional child (ages 0-17) living at home, there was an average estimated 10% decrease in the proportion of women employed. It is also notable that regional levels of employment vary widely for a given number of children at home (see Figure 3). Most sub-Saharan African countries have substantially higher levels of employment on average than countries in Asia, Latin America, and Southern Africa, even with similar numbers of children residing at home. Employment among women is lowest in the Middle East and North Africa, regardless of the number of children living at home.

While the magnitude of the association varies substantially by region, its negative sign is evident in all of these disparate contexts, with both high and low levels of female employment. Simply put, the more children they have living with them, the less likely women are to be employed. And the negative effect is greatest for younger children and for women in ‘modern’ occupations, such as professional and managerial positions.

While having children at home makes it more difficult for women to work, those who want or need to work may also choose to have fewer children. Women and their families are likely to make decisions about work and children multiple times throughout their lives as their circumstances change. However, the number of children may have little to do with employment if work is needed for subsistence, as is often the case among the poorest women. To account for this complexity in a statistical analysis would require the kind of detailed data that are rarely collected in LMIC settings.

Reproductive choice and economic opportunity

Childcare is still mostly women’s responsibility in most places and children are more likely to live with their mothers than their fathers, including in developed nations. Women provide the majority of childcare and elder care , a type of work which is largely uncounted in labor statistics (Chopra 2015) and which is generally characterized by low or no pay and lack of social protection (ILO 2016). At the same time, the standards and practices of childcare differ among societies. For example, in some countries, it is not only commonplace but generally accepted that a mother can bring her young child to work with her, particularly if she is a market trader or an agricultural worker. In others, women in paid employment typically leave their children in the care of others.

The strength and nature of the labor market for women also plays a role in the extent to which childbearing and childrearing affect women’s employment. Gender inequalities in opportunity, the lack of gender considerations in economic policies, and discrimination in remuneration are all important factors.

Access to reproductive choice via the use of family planning opens up a new world of possibility for women. Without the ability to control their own fertility, women are limited in their opportunity to participate in the labor force, to fulfill their potential, and to contribute to their own economic well-being and that of their households, families, and communities (McCauley 1994; McNay 2005).

The ability to determine their own reproductive future is of paramount importance for women, but it does not address broader, structural issues that limit women’s economic empowerment. If we hope to harness the economic contributions of the entire population, women must be able to contribute meaningfully. When the dual roles of mother and worker are incompatible, women’s choices around having children and contributing economically are both constrained. This means that families, governments, and societies need to take steps to reduce the multiple barriers to women’s full participation in the economy.

References

Bongaarts, John, Ann K. Blanc & Katharine J. McCarthy (2019) The links between women’s employment and children at home: Variations in low- and middle-income countries by world region, Population Studies, 73:2, 149-163, DOI: 10.1080/00324728.2019.1581896

Chopra, D. (2015). Balancing Paid Work and Unpaid Care Work to Achieve Women’s Economic Empowerment. IDS Policy Briefing No. 83, Brighton: Institute of Development Studies (IDS).

International Labor Organization (ILO) (2016) Women at Work: Trends 2016. Geneva. doi:10.1038/443131a

Lee, M. and J. Finlay (2017). The Effect of Reproductive Health Improvements on Women’s Economic Empowerment: A Review Through the Population and Poverty (POPPOV) Lens. Washington, DC: Population and Poverty Research Initiative and Population Reference Bureau.

McCauley, A. P., B. Robey, A. K. Blanc, and J. S. Geller. (1994) Opportunities for women through reproductive choice. Population Reports 12: 1-39.

McNay, K. (2005) The implications of the demographic transition for women, girls and gender equality: A review of developing country evidence, Progress in Development Studies5(2): 115-134. doi: 10.1191/1464993405ps109oa