Poland’s ambitious “Family 500+” program offered substantial monthly payment to families with children. While the program modestly increased overall fertility in the short-term, its effects varied significantly by age and income, suggesting, in Anna Bokun’s opinion, that financial incentives alone may not be enough to reverse declining birth rates in low-fertility countries.

The context

In 2016, Poland launched one of Europe’s boldest experiments in boosting birth rates – a monthly payment of 500 złoty (about 130 USD) for each child in families with two or more children. The policy aimed to lift Poland out of its “lowest-low fertility” trap, where women were having on average just 1.3 children in the mid-2010s, far below the replacement level of 2.1.

What made this program unique was its scale and simplicity. Rather than complex tax credits or targeted subsidies, Poland opted for direct cash transfers, amounting to about 25% of the minimum wage. By 2018, over half of all Polish children under 18 were receiving these benefits (PSO 2018).

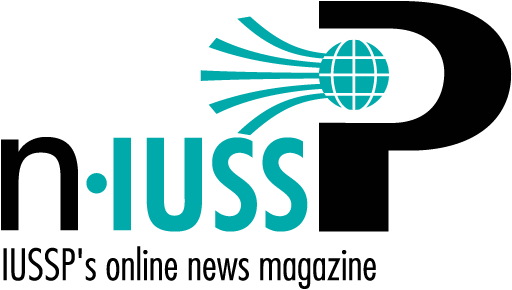

This bold policy shift came at a critical time. Like many European countries, Poland had experienced a dramatic fertility decline since the 1990s. The transition from communism – alongside social changes of the last few decades – brought economic uncertainty, delayed marriages, and changing attitudes toward family size. By 2015, Poland had the lowest fertility rate in the European Union, prompting concerns about population aging and its implications for economic growth and social systems. Figure 1 tracks the total fertility rate in Poland over the last two decades.

The program

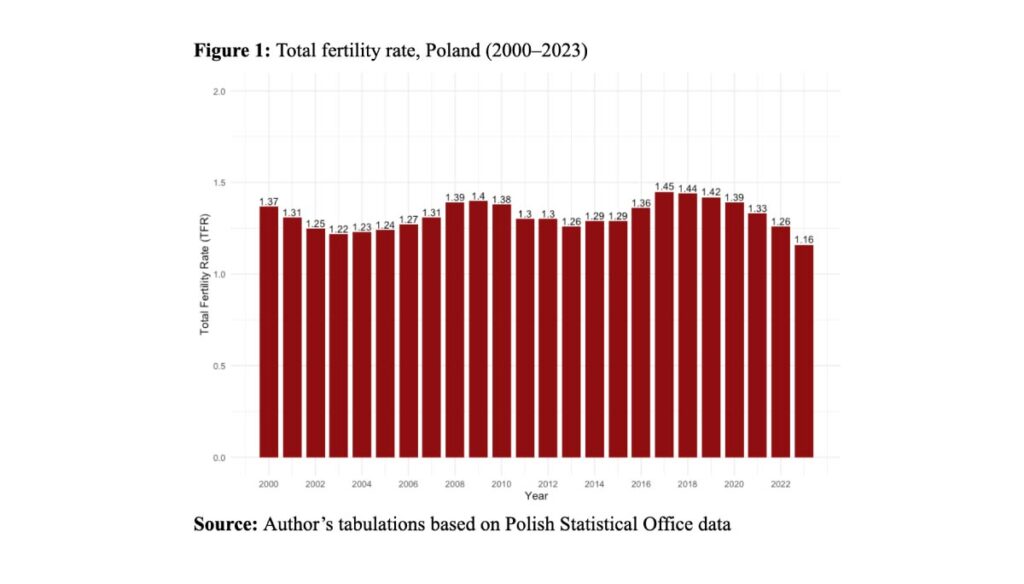

The “Family 500+” program represented an unprecedented investment in Polish families, accounting for about 2% of GDP by 2017 (Figure 2). Poland’s family benefits system shifted from giving relatively equal weight to cash transfers, tax breaks, and services to favoring cash transfers by a large margin, quadrupling the amount of money flowing to families in the form of direct cash between 2010 and 2017. Unlike previous policies, it provided substantial, predictable monthly income that families could count on through their children’s early years. The benefit was universal for families with two or more children, regardless of income level or parental marital status, making it simple to administer and free from stigma that may be associated with some social safety net programs.

Results

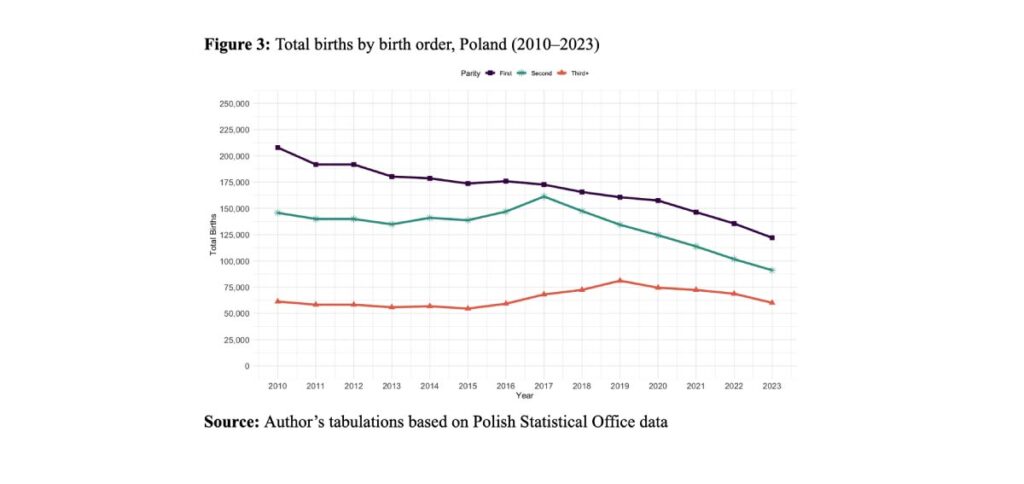

The results, however, tell a nuanced story. In my analysis (Bokun 2024), I found that the program increased the overall probability of having a child by 1.5 percentage points (Figure 3). But this modest average effect masks important variations across different groups:

• Women aged 31–40 were most responsive to the policy, showing increased fertility (0.7-1.8 percentage points).

• Younger women aged 21–30 were less likely to respond to the policy, and their fertility declined (–2.2-2.6 percentage points).

• Higher-income households were less likely to have additional children (–1 percentage point).

Age matters

Women aged 31–40 showed increased fertility in response to the program – a pattern consistent with findings from similar policies in other places, from Israel to Alaska (Cowan and Douds 2022). This aligns with a broader European trend of increasing fertility among older women, particularly for first and second births (Beaujouan 2020). As more women prioritize education and career establishment in their 20s, childbearing in one’s 30s has become increasingly common.

Why did younger women have fewer children despite the financial support? The answer reveals the complex psychology of family planning. The program, with its pro-natal intent might have signaled a commitment to family support, paradoxically encouraging some young women to delay childbearing. Knowing that financial support would be available in the future, they might have felt more comfortable waiting until after completing education or establishing careers.

There is also evidence that younger women might resist what they perceive as government pressure to have children. While older women might view the benefit as financial support, younger women may see it as an attempt to influence their personal life choices (Botev 2015).

Why did higher-income families respond differently?

Higher-income families responded less to the policy. Three key factors help explain why:

• The quality-quantity tradeoff: Families with higher incomes tend to invest more resources in each child rather than having more children. For higher-income women, the monthly cash transfer might not be a strong enough incentive to sacrifice career advancement and future earnings to have another child.

• Relativity of financial support: Since child-rearing costs consume a larger share of lower-income families’ budgets, the 500 złoty (130 USD) monthly benefit went further for them (Gromadzki 2024). For low-income families, it might cover significant portions of basic needs. For higher-income families, however, the amount represents a much smaller fraction of their expenditures on each child.

• Cross-national comparisons: In today’s highly migratory European Union, Polish families often compare their living standards not only to the past, but to wealthier countries in Western Europe (Marczak, Sigle and Coast 2018). Although living standards have greatly improved in Poland over the last two decades, relative perceptions of disadvantage may influence childbearing decisions and inadvertently lower fertility.

• Implications: Beyond fertility, the program had other effects. Studies show it successfully reduced child poverty and inequality, suggesting that even if fertility goals aren’t fully met, such policies can improve family well-being (Cook, Iarskaia-Smirnova and Kozlov 2023). However, some research indicates that the program may have reduced female labor force participation and consequently, women’s economic autonomy, highlighting the unintended consequences of some family benefits programs.

The Polish experience offers valuable lessons for other countries considering similar policies. First, the effects of cash transfers on fertility are likely to be modest and vary significantly across different population groups. Second, timing matters – the impact appears strongest in the short term, weakening over time. Third, financial incentives alone may not address the fundamental factors driving low fertility, such as the challenges of balancing work and family life.

The decline in communal support structures may also help explain low fertility rates in wealthy nations. Historically, communities and neighborhoods played a vital role in easing the burdens of raising children, and families relied on informal support networks—neighbors, relatives, and peer groups of children—that created a shared responsibility for childcare. Modern parenting, on the other hand, has become increasingly intensive and isolated – parents spend more time directly supervising their children but have less community support.

This is important for policymakers. Policies that integrate family-friendly practices into communities, such as accessible and affordable childcare, flexible workplaces, and neighborhood-level support networks, may help alleviate some of the pressures that families face. Rebuilding community infrastructure could be as important as financial incentives in supporting families.

Poland’s experience offers lessons for other countries grappling with low fertility. Cash transfers can help, but their success depends on how well they align with the diverse needs of families.

References

Beaujouan E. (2020) Latest-Late Fertility? Decline and Resurgence of Late Parenthood Across the Low-Fertility Countries. Popul Dev Rev.;46(2):219-247. doi:10.1111/padr.12334

Bokun A. (2024) Cash transfers and fertility: Evidence from Poland’s Family 500+ Policy, Demographic Research, 51(28) : 855–910

Botev N. (2015) Could Pronatalist Policies Discourage Childbearing? Popul Dev Rev.;41(2):301-314. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00048.x

Cook LJ, Iarskaia-Smirnova ER, Kozlov VA (2023) Trying to Reverse Demographic Decline: Pro-Natalist and Family Policies in Russia, Poland and Hungary. Soc Policy Soc.;22(2):355-375. doi:10.1017/S1474746422000628

Cowan SK, Douds KW (2022) Examining the Effects of a Universal Cash Transfer on Fertility. Social Forces, 101(2):1003-1030. doi:10.1093/sf/soac013

Gromadzki J (2024) Universal Child Benefit and Child Poverty: The Role of Fertility Adjustments. SSRN Electronic Journal, Published online. doi:10.2139/ssrn.5025534

Marczak J, Sigle W, Coast E (2018) When the grass is greener: Fertility decisions in a cross-national context, Population Studies, 72(2):201-216. doi:10.1080/00324728.2018.1439181

PSO – Polish Statistical Office (2018) Household Budget Survey in 2018. Statistics Poland – Accessed December 18, 2024.