Despite a large number of unauthorized immigrants entering the United States across the U.S.-Mexico border, the size of the undocumented foreign-born population remained almost constant at around 11 million between 2010 and 2020. Jennifer Van Hook tells us why.

Between 2010 and 2020, large numbers of unauthorized immigrants crossed the border into the U.S. each year. This steady inflow appeared to challenge demographic estimates showing slow growth in the population of unauthorized immigrants, whose number hovered around 11 million throughout the decade. Why did these estimates remain almost the same year after year despite the nearly continuous influx of new arrivals?

The reason is that migration is a two-way process. Just as new undocumented immigrants enter the U.S. each year, others leave, die, or legalize their status. In a recent article, I show that outflows among unauthorized migrants have been substantial (Van Hook 2024).

Inflows are offset by outflows

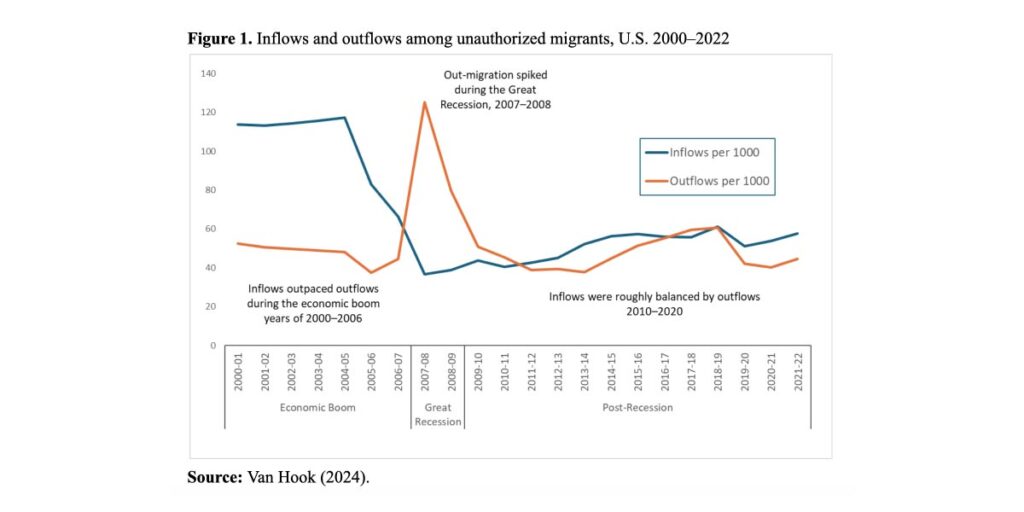

Populations grow only when inflows outpace outflows. Figure 1 shows the number of unauthorized migrant inflows (blue) and outflows (orange) per 1,000 U.S. population. During the economic boom years of 2000 to 2006, inflows far exceeded outflows, and the unauthorized population grew by over half a million per year. This period was marked by rapid economic growth and high demand for foreign labor from Mexico and Central America in the construction and service sectors.

With the onset of the Great Recession, however, work opportunities evaporated. Many people lost their jobs, including unauthorized immigrants, and some went back to their home countries. At the same time, many would-be migrants opted to stay home. In-migration dropped, out-migration spiked, and the unauthorized population declined by 1.5 million in the space of just two years.

Since about 2010, inflows have been more closely balanced by outflows. Between 2010 and 2020, 5.6 million unauthorized immigrants entered the country or overstayed a visa, while 5.1 million died, legalized or emigrated. The close correspondence between inflows and outflows helps explain why the overall number of unauthorized immigrants during this period grew by less than half a million during the decade, from 10.6 million in 2010 to 11.0 million in 2020.

Duration of stay

To understand why outflows occur, it is helpful to consider the trajectory of the average migrant. Using a common demographic technique, the life table, I found that the average migrant is likely to remain in an unauthorized legal status for 16 years. This is a long time but not a lifetime. Fully one-third are no longer unauthorized migrants within ten years of entering the country.

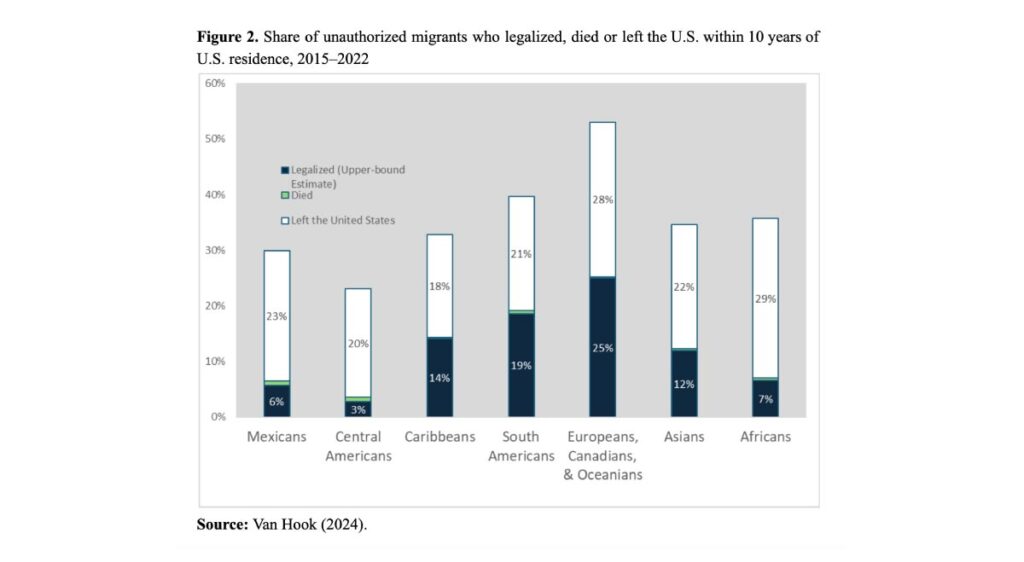

Most of these outflows take the form of out-migration. At least 23 percent of unauthorized migrants appear to leave the country within ten years. In contrast, only 11 percent find ways to legalize, and 1 percent die. The 11 percent who legalize is an upper-bound estimate. It is based on the information available to the public from the Department of Homeland Security on all immigrant adjustments and not just those who adjust from an unauthorized to a legal immigration status.

The time migrants spend living with an unauthorized migration status varies across groups (Figure 2). Mexicans and Central Americans spend the longest time. They can expect to live undocumented in the United States for an average of 22 years. After ten years of residence, roughly 20 percent will have returned home and only 6 percent of Mexicans and 3 percent of Central Americans will have legalized. These low legalization rates reflect their limited options under U.S. immigration law. As poor labor migrants with low levels of education, their chances of legalizing under employment-based classes of admission are slim. Additionally, many crossed the U.S.-Mexico border without inspection (by evading immigration checkpoints or being smuggled into the country), so are subject to laws that forbid them from adjusting status without first leaving the U.S. for many years.

This contrasts with migrants from other parts of Latin America, Asia, Europe, and Africa. On average, they can expect to spend 11 years in unauthorized status before leaving, adjusting to legal permanent residence status, or dying, half the average duration of Mexicans and Central Americans. Europeans, Canadians and Oceanians stand out, with 25 percent leaving the country and up to 25 percent legalizing within 10 years. A large share of these migrants overstayed a student or work visa and are highly educated. They may not want to stay in the U.S. because they have opportunities elsewhere, and those who do stay may be able to legalize through employment or family visas.

Declines in duration

The duration spent in unauthorized status has been declining over the last two decades. Between 2000 and 2006, the average was 22 years. With the onset of the Great Recession, however, return migration rates rose three-fold. The average duration declined to 16 years and remains at this level today.

These changes happened because groups that spend a long time in unauthorized status (Mexicans and Central Americans) are gradually being replaced by groups with shorter durations. Between 2007 and 2022, the number of Mexican-born unauthorized immigrants dropped from 7.7 to 5.1 million. At the same time, the share from all other regions increased, and these newer groups tend to spend less time in an unauthorized status than Mexicans.

Looking ahead

The latest estimates of the unauthorized population do not extend beyond 2022 and do not fully capture recent increases in entries at the U.S.-Mexico border. Encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border surged more than four-fold from 401,000 in 2020 to 1.7 million in 2021, and then further increased to 2.4 million in 2022 and 2.5 million in 2023. As more data become available, we expect to see growth in the unauthorized foreign-born population, but it remains unclear how much growth. That will depend on how long new arrivals remain in the country in an unauthorized status. Despite these uncertainties, the overarching trend is clear. Large shares of unauthorized immigrants leave the country or legalize, and they are less “permanent” now than two decades ago.

References

Van Hook Jennifer (2024) Beyond Stocks and Surges: The Demographic Impact of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population in the United States. Population and Development Review, online first, https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12683