Childlessness in Korea is rising due to delayed marriage, increasing singleness and a growing share of childless unions. Misun Lee and Kryštof Zeman show that while more years in education postpones childbearing, other social, cultural, and economic factors are contributing to this trend across all educational levels.

Childlessness is on the rise in the Republic of Korea (hereafter Korea). Traditionally, marriage and motherhood were closely linked, but this relationship has weakened in recent years. Despite persistent government efforts to raise fertility rates, the proportion of women who remain childless has increased substantially. The root of this trend lies in a combination of delayed marriage and increasing singleness (Sobotka, 2017).

Education first, partner and children later (maybe)

At the heart of this transformation is the expansion of higher education among women. By 2020, 70.5 % of women aged 25 to 29 had completed tertiary education, dramatically rising from a mere 1.7 % in 1980. Many women now opt to complete their studies before considering marriage or motherhood (Neels et al., 2017), and this postponement shortens their childbearing years, raising the chances of remaining childless. However, education alone does not fully account for the rise in childlessness. Indeed, the decomposition analysis carried out in our original study (Lee and Zeman, 2024) shows that the increase in childlessness between the 1965 and 1980 birth cohorts depends more on the growing proportion of never-married women and the broader postponement of marriage than on educational expansion. While it correlates with later marriage and its fertility consequences, rising childlessness is observed across all educational levels, including among low-educated women (Hwang, 2023). This points to broader social and economic factors behind this trend.

Marriage postponement and the rise of marital childlessness

Marriage postponement is one of the clearest indicators of rising childlessness in Korea. The average age at first marriage increased from 24.9 years in 1992 to 31.3 years in 2022. Female educational expansion and changes in women’s roles in society have pushed marriage and, subsequently, childbirth, further into the future for many women (Yoo, 2014). As marriage is delayed, the window of opportunity for having children narrows, increasing the likelihood of childlessness.

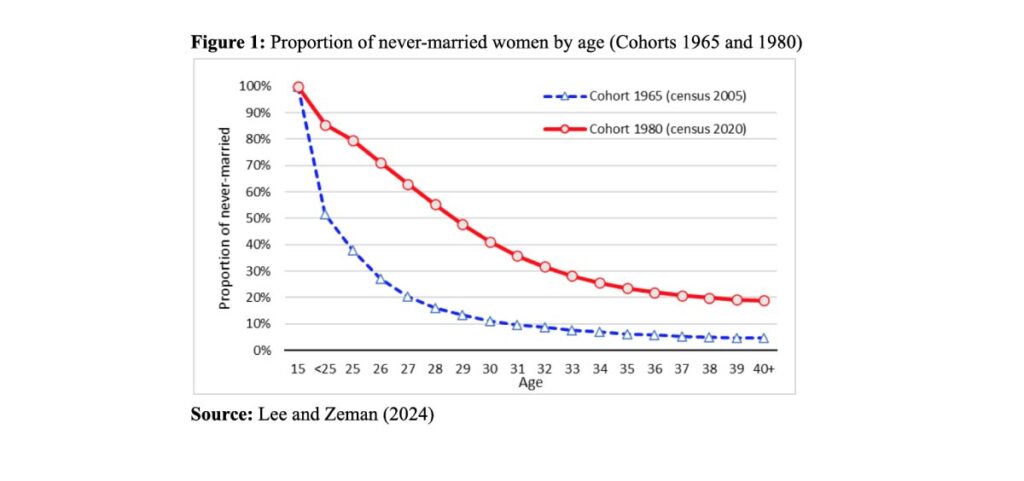

Indeed, the proportion of never-married women has increased remarkably (Figure 1). In the 1965 cohort, about half of Korean women were married by age 25, but by 2020, this milestone was not reached until age 29. Over the same period, the proportion never-married at age 40 rose substantially, from 4.7% to 18.9%. In both cohorts, low-educated women tend to marry earlier, but eventually, at age 40, the differences in terms of proportions married are minimal.

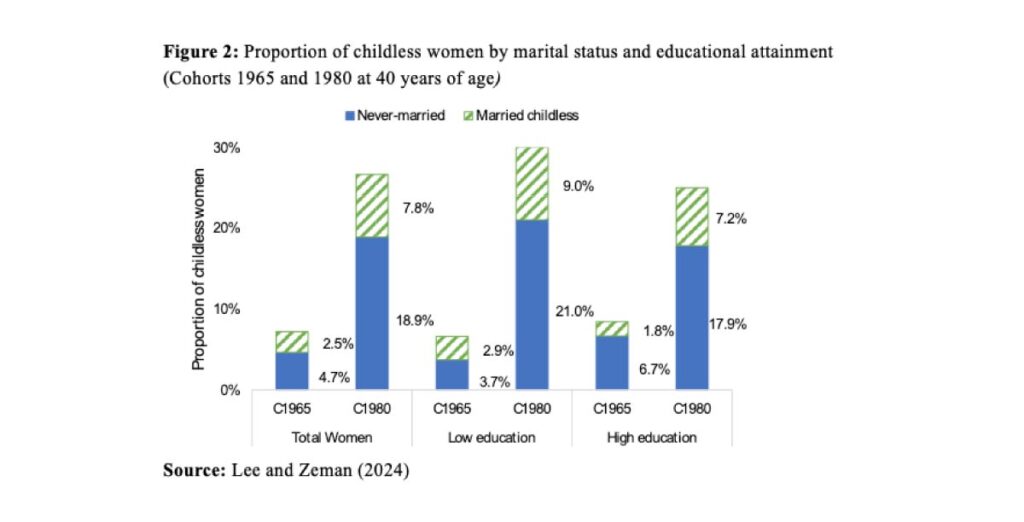

Marriage postponement and marital childlessness are closely linked, although the causal chain is probably more complex than the simple correlation would suggest, as both phenomena seem to stem from the profound changes in Korean society over the past decades. Figure 2 reports the proportion of childless women aged 40, segmented by marital status and educational background. The increase in childlessness is substantial, particularly among never-married women.

Beyond education: broader changes in marital behaviour

As changes in marital behaviour are similar across educational levels, other factors beyond increasing education are indeed at play. The broader societal transformation in Korea, shifting values around marriage, family, and gender roles, and factors such as economic pressures, workplace challenges, and gender inequality are reshaping women’s decisions around childbearing (Brinton and Oh, 2019; Yoon, 2016).

In conclusion, the rising rates of childlessness in Korea span all educational levels, with delayed marriage and an increasing number of never-married women being the most significant contributing factors. While spending more time in education does play a role in delaying marriage, wider societal and economic changes are reshaping women’s choices around marriage and motherhood. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for policymakers addressing Korea’s demographic challenges, including its rapidly declining fertility rates.

References

Brinton, M. C., & Oh, E. (2019). Babies, Work, or Both? Highly Educated Women’s Employment and Fertility in East Asia. American Journal of Sociology, 125(1), 105–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/704369

Hwang, J. (2023). Later, Fewer, None? Recent trends in cohort fertility in South Korea. Demography, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-10585316

Lee, M., & Zeman, K. (2024). Childlessness in Korea: Role of education, marriage postponement, and marital childlessness. Demographic Research, 51, 669–686. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2024.51.21

Neels, K., Murphy, M., Ní Bhrolcháin, M., & Beaujouan, É. (2017). Rising Educational Participation and the Trend to Later Childbearing. Population and Development Review, 43(4), 667–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/PADR.12112

Sobotka, T. (2017). Childlessness in Europe: Reconstructing Long-Term Trends Among Women Born in 1900–1972. In J. Vaupel (Ed.), Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences (pp. 17–53). Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7

Yoo, S. H. (2014). Educational differentials in cohort fertility during the fertility transition in South Korea. Demographic Research, 30. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.53

Yoon, S.-Y. (2016). Is gender inequality a barrier to realizing fertility intentions? Fertility aspirations and realizations in South Korea. Asian Population Studies , 12(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2016.1163873