The introduction of unilateral divorce legislation in the US in the 1970s and 1980s, which led to spikes in divorce rates, coincided with rising educational assortative matching into marriage. Geghetsik Afunts and Stepan Jurajda suggest these two trends were related.

Since the early 1970s, educational homogamy, the tendency to assortatively match into marriage based on educational level, has increased significantly in the US. At the same time, hypogamy, the tendency for highly educated women to marry down in education, has also increased from very low levels. The share of homogamous and hypogamous marriages in the stock of prevailing marriages has increased at the expense of hypergamy (women marrying more educated partners). These trends in marriage stock must correspond to changes in the educational structure of marriage inflow, i.e., among newlyweds, and/or selective marriage outflow, i.e., divorce patterns, where homogamous and hypogamous marriages are more stable and accumulate in the marriage stock. It has been shown that homogamous marriages are indeed more stable, such that the educational structure of divorce has contributed to the rise in educational homogamy in the marriage stock (e.g., Schwartz, 2010).

Unilateral divorce legislation in the US

The period of rising homogamy and hypogamy has also been characterized by a dramatic increase in divorce rates, partly attributed to the adoption of unilateral divorce legislation (UDL). Between 1970 and 1988, 29 US states changed their marriage dissolution laws to a unilateral system, which allows a person to divorce without the agreement of his or her spouse, even in absence of a fault. In an influential analysis, Wolfers (2006) studied state divorce rates up to 1988 and concluded that the adoption of UDL sharply increased divorce rates, but that this effect dissipated within a decade of the legislative reform. Whether UDL affected marriage rates is less clear.

To date, these two major marriage-market trends ‒ rising educational homogamy/hypogamy and rising divorce rates ‒ are studied in largely separate literatures. Despite the evidence on the importance of UDL for overall divorce rates, and on the importance of the educational structure of divorce for rising homogamy in the marriage stock, little is known about whether UDL affected the educational structure of divorce, or likewise, the educational structure of newlyweds. In a recent study (Geghetsik and Jurajda, 2024), we asked whether UDL-induced higher divorce risks affected the educational structure of marriage inflow and outflow. To estimate these UDL effects, we leveraged the different timing of UDL introduction across US states.

Our analysis relies on precise measures of the educational structure of marriage inflows and outflows by state and year based on under-utilized US administrative data from registered certificates of marriages and divorces over the period 1970‒1988. Unlike survey data, the administrative records allow us to study the educational composition of marriage inflows and outflows within an analytical difference-in-differences framework. We study first and higher-order marriages separately, because it is well known that highly educated women entering higher-order marriages face a ‘marriage squeeze’ (Qian & Lichter, 2018), i.e., find it difficult to match to equally educated partners.

Over the period 1970‒1988, divorce was least likely for homogamous marriages, almost as unlikely for hypergamous marriages but high for hypogamous marriages. We find that much of the stability advantage of homogamy plays out within the first two years of marriage. This is relevant to the study of marriage inflows using survey data, in which newlyweds are identified as those recently married, because such samples are affected by survival bias due to differential divorce rates across marriage types, even in samples of marriages that occurred at most two years before the survey interview.

Newlyweds

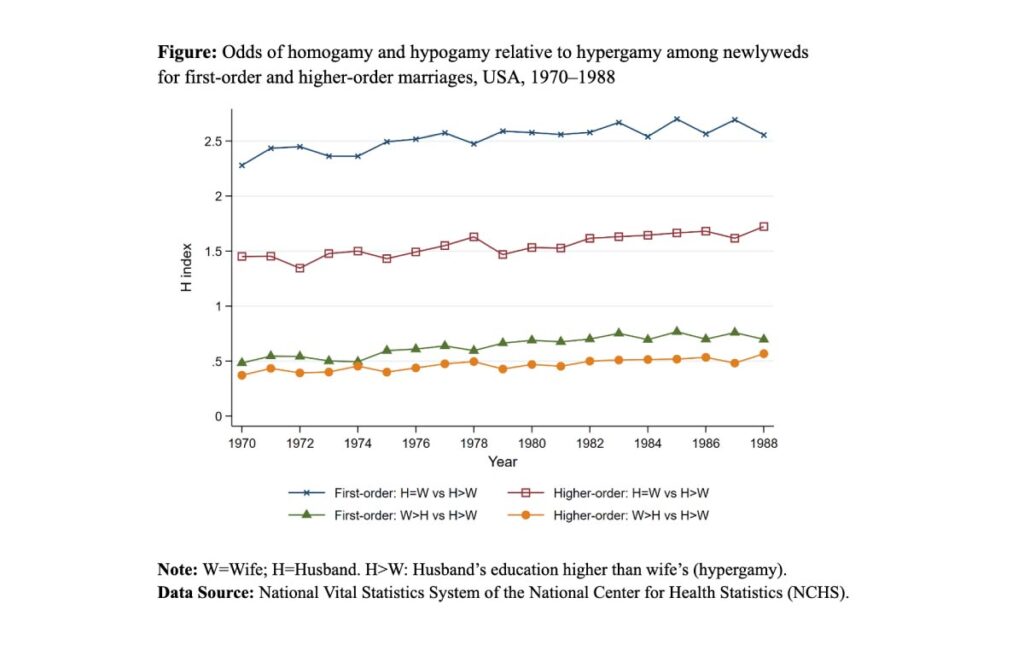

Turning to newlyweds, we find that homogamy among newlyweds did not increase relative to non-homogamy during our study period. However, there were significant changes in the educational structure of US marriage inflows: The odds of hypogamy increased relative to hypergamy, and so did the odds of homogamy relative to hypergamy (see Figure).

Next, we assess the role of UDL for educational sorting in marriage inflows and outflows. We find no evidence that making divorce easier affected the educational structure of marriage inflow, but we uncover robust evidence based on first marriages that UDL lowers the stability of hypergamous marriages relative to homogamous ones, and that it also reduces the large stability disadvantage of hypogamous couples relative to hypergamy. We thus depict a marriage market where, among newlyweds, ‘traditional’ hypergamous marriages are losing ground to both homogamy and hypogamy, and where hypogamous marriages are more likely to end in divorce. These patterns hold for both first and higher-order marriages. With the introduction of unilateral divorce legislation (UDL), the picture changes substantially for first marriages, but not for higher-order ones. Among first marriages, UDL has improved the stability of hypogamous marriages and lowered that of hypergamous ones, while homogamy is starting to enjoy a stability advantage over hypergamy. In sum, we find that UDL contributed to the rise in homogamy.

Underlying mechanisms

We uncover two mechanisms behind these changes. First, we find that UDL disproportionately leads to less educated wives in hypergamous marriages initiating divorce, which underpins the reduction in the stability gap between hypergamous and hypogamous first marriages. Second, our findings suggest that highly educated women entering their first marriage are able to compensate for the higher (perceived) riskiness of marriage under UDL by forming more stable matches in terms of match quality dimensions other than education. This compensation mechanism appears particularly strong for hypogamous first marriages, consistent with the reduction in their stability disadvantage under UDL. We thus provide support for an under-researched response in marriage formation behavior, where the quality of matches in formed unions is influenced by norm- or regulation-induced changes in expected union stability. Such an adjustment mechanism has been suggested for couples entering cohabitation, because leaving cohabitation is easier than leaving marriage (Schoen and Weinick, 1993), and is also one of the consequences of the introduction of UDL in a marriage market model proposed by Reynoso (2024).

References

Afunts, G. & Jurajda, S. (2024). Who Divorces Whom: Unilateral Divorce Legislation and the Educational Structure of Marriage. Demography, online first.

Qian, Z. & Lichter, D. T. (2018). Marriage markets and intermarriage: Exchange in first marriages and remarriages. Demography, 55(3), 849–875.

Reynoso, A. (2024). The impact of divorce laws on the equilibrium in the marriage market. Journal of Political Economy, in press.

Schoen, R. & Weinick, R. M. (1993). Partner choice in marriages and cohabitations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 55(2), 408.

Schwartz, C. R. (2010). Pathways to educational homogamy in marital and cohabiting unions. Demography, 47(3), 735–753.

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1802–1820.