The racial divide is still profound in the U.S., in terms not only of survival, and survival without disabilities, but also of happiness. Anthony R. Bardo and Jason L. Cummings document some of these disparities.

Now that they are growing old, have US baby boomers fulfilled the aspirations towards more positive and equitable life circumstances that characterized their youth, especially through the Civil Rights movement? One way to address this question is to focus on life expectancy, the number of remaining years that an average person can expect to live, and to analyze racial disparities in length of life.

Trends in American longevity and physical disability

In 1970, life expectancy at birth in the US was approximately eight years longer for Whites than for Blacks: 71.7 vs 64.1 years, respectively. By 2010 this racial gap had narrowed to slightly less than four years: 78.9 vs. 75.1 years, respectively. More recent data are difficult to compare because of the pervasive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, but national vital statistics suggest that some progress seems to be underway.

Both survival increase and convergence are good news, of course, but it is also important to consider if these additional years are lived in good health, both in general and by subgroup. For instance, let us consider active life expectancy at age 65, or remaining years of life past the 65th birthday expected to be lived without a disability. Between the 1980s and 2010s, it increased by 2.8 years for White Americans (from 12.2 to 15.0 years) and 2.2 years for Black Americans (from 9.8 to 12.0 years). This means that the percentage of remaining years of life expected to be lived without a disability remained approximately constant, but at different levels: 76% for White people but only 67% for Blacks (Freedman & Spillman, 2016). In other words, increases in life expectancy were accompanied by an equivalent number of healthy and unhealthy years, and racial disparities remained unchanged.

Racial disparities in long and happy living

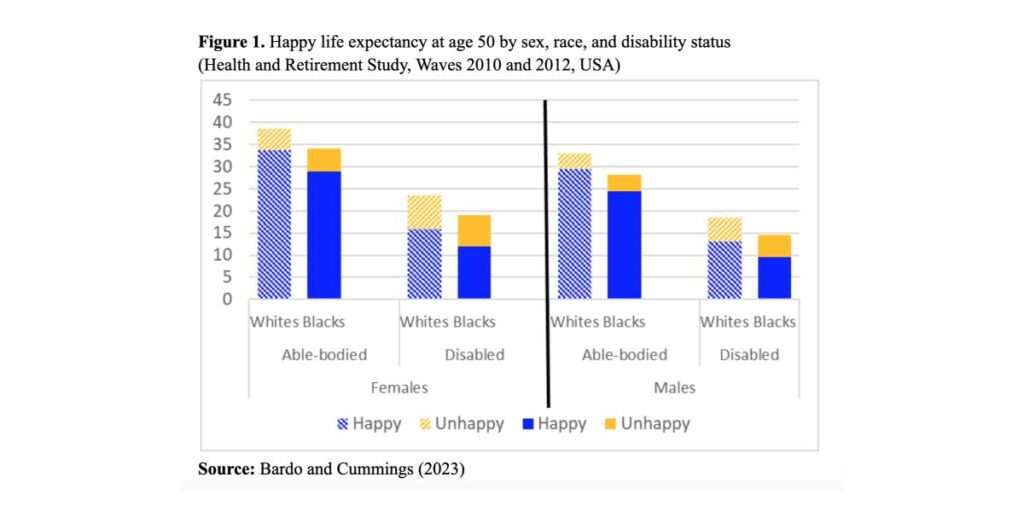

While life expectancy and active life expectancy are key objective indicators of quality of life, at high levels of development, additional indicators of well-being can also be considered. One such indicator links this survival to subjective well-being, a facet of societal progress that has recently garnered wide-spread attention (Layard, 2010). Until now, few researchers have tried to determine happy life expectancy, i.e., how many years an individual can expect to live happily. This is precisely what we did in a recent study, breaking our results down by physical disability status, sex, and race (Bardo and Cummings 2023) based on representative data from the 2010 and 2012 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (n = 16,614) of the U.S. population aged 50 years and older.

The emergence of health problems is, of course, a normal and anticipated part of the aging process, and, within limits, worsening health is not a strong determinant of happiness in later life, because individuals assess their quality of life based on their expectations and ability to adapt or adjust to changing circumstances. However, the development of a disability reflects a major life change, with clear and negative consequences for both quality of life and longevity. For example, at age 50, White Americans with a disability can expect to live happily for 50% fewer years of their remaining life than their able-bodied peers. The negative influence of disability on happy life expectancy is exacerbated for Black Americans who experience a 60% reduction in remaining happy years of life when faced with a disability. These findings portray the compounding effects of cumulative (dis)advantage and circumstances that people with multiple intersecting identities (e.g., Black, male, disability) uniquely experience (Figure 1).

Unfortunately, in the USA, racial disparities in key resources that promote health, happiness, and longevity remain as wide today as they were in the 1970s, as, for example, in the case of the Black-White gap in median household income. Do socioeconomic differences account for racial disparities in happy life expectancy? As our analyses indicate, they do for healthy Black women but not for healthy Black men. The reasons behind this unexpected result are not self-evident, and merit further analysis.

Conclusion

There is no simple solution for achieving equity in opportunities to live a long, healthy and happy life. We focused on later life outcomes, but these are the consequences of cumulative chronic exposure to various race-related forms of stress and discrimination experienced throughout life, including uneven access to high quality primary/secondary education and safe housing in childhood, unequal access to quality jobs and affordable and safe housing during adulthood, and likely the high risk of imprisonment for young Black males (Gilbert et al., 2016).

It is high time that America turned attention towards the disparities in length and quality of life that persist in the land where the pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness is a supposedly unalienable right.

References

Bardo, A.R., Cummings, J.L. (2023) Life, Longevity, and the Pursuit of Happiness: The Role of Disability in Shaping Racial and Sex Disparities in Living a Long and Happy Life. Population Research and Policy Review. 42, 72.

Freedman, V. A., & Spillman, B. C. (2016). Active life expectancy in the older US population, 1982–2011: Differences between blacks and whites persisted. Health Affairs, 35(8), 1351–1358.

Gilbert, K. L., Rashawn, R., Siddiqi A., Shetty, S., Baker, E.A., Elder, K. & Griffith, D.M. (2016). Visible and invisible trends in black men’s health: pitfalls and promises for addressing racial, ethnic, and gender inequities in health. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 295-311.

Layard, R. (2010). Measuring subjective well-being. Science, 327, 534-534.