In India, the percentage of male births has increased since the mid-1980s. Claus Pörtner ties the continuously growing use of prenatal sex selection to India’s falling fertility among highly-educated women. He shows how sex selection substantially lengthens birth intervals, which, in turn, is responsible for a significant downward bias in the total fertility rate compared to predicted cohort fertility. Less-educated women still have relatively high fertility and short birth intervals when they have no sons, negatively affecting girls’ survival chances.

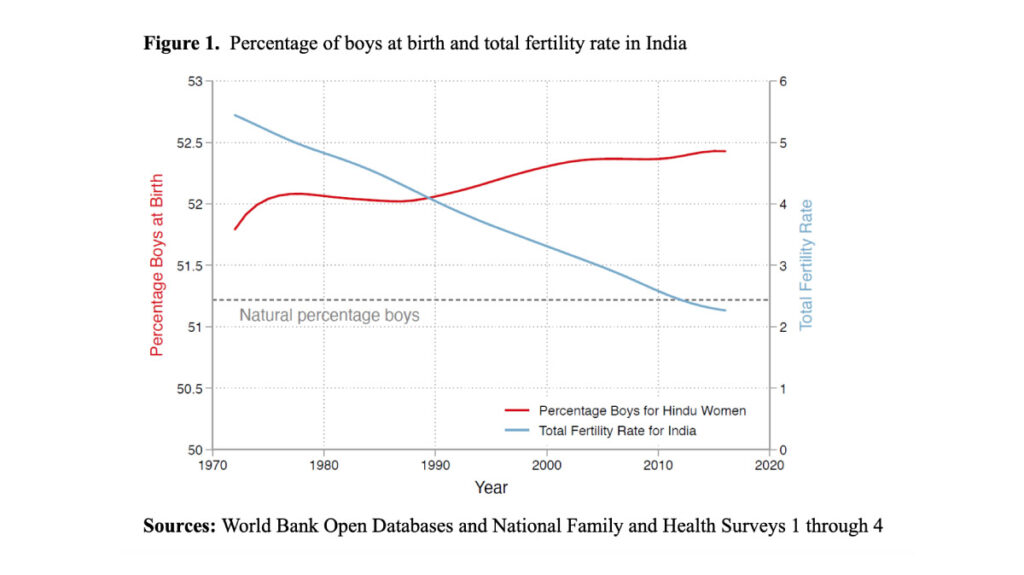

With the introduction of ultrasound in the mid-1980s, use of sex-selective abortion spread rapidly in India, as shown by the steadily increasing percentage of boys in Figure 1. However, access to pre-natal sex determination does not necessarily lead to sex selection. Rather, in India, the practice is driven by the combination of declining fertility (also shown in Figure 1) and the particular Hindu preference for a son. However, once that son is secured, there is no clear son preference for subsequent births (Jayachandran, 2017; Pörtner, 2015). If a family is willing to have up to six children, there is a 99% probability of achieving the goal of one son. But if the desire is for one son and a maximum of two children, about 25 percent of families must use sex selection to achieve both targets.

Three critical aspects

As striking as these overall numbers are, they obscure three critical aspects of the changes in India:

• first, the massive differences in use of sex-selective abortion across education levels that followed the availability of pre-natal sex determination;

• second, significant differences in use of sex selection by parity;

• third, the increase in birth intervals brought about by sex selection, which, in turn, has led to substantial overestimation of the rate of fertility decline in India.

In a recent paper, I use data from India from 1972 to 2016 to examine how fertility, sex ratio, and birth spacing changed by education level with the spread of sex selection (Pörtner, 2022). The data comes from the first four National Family and Health Surveys. I focus on Hindu women because Hindus constitute about 80% of India’s population and have shown stronger son preference and higher use of sex selection than Muslims.

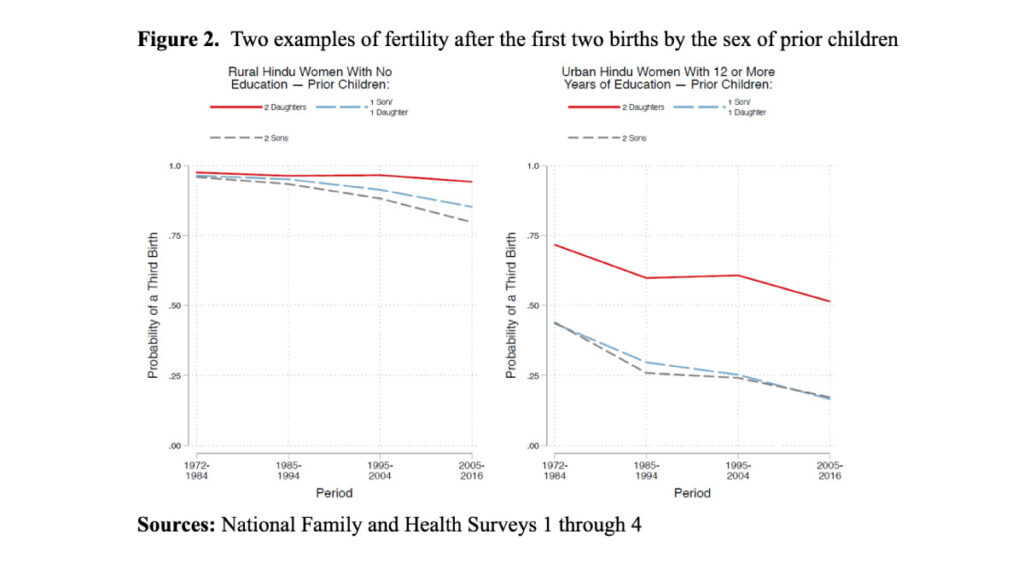

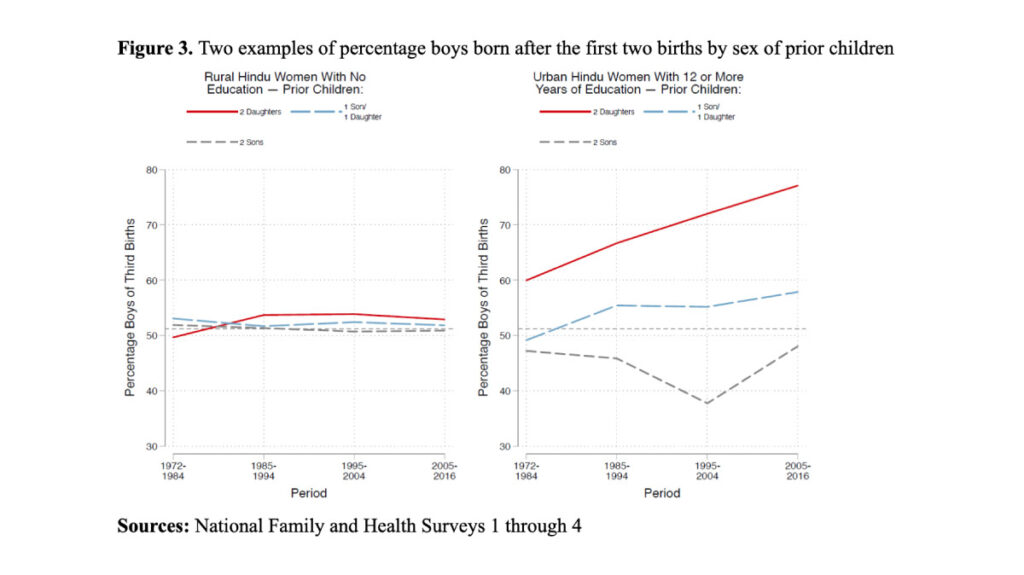

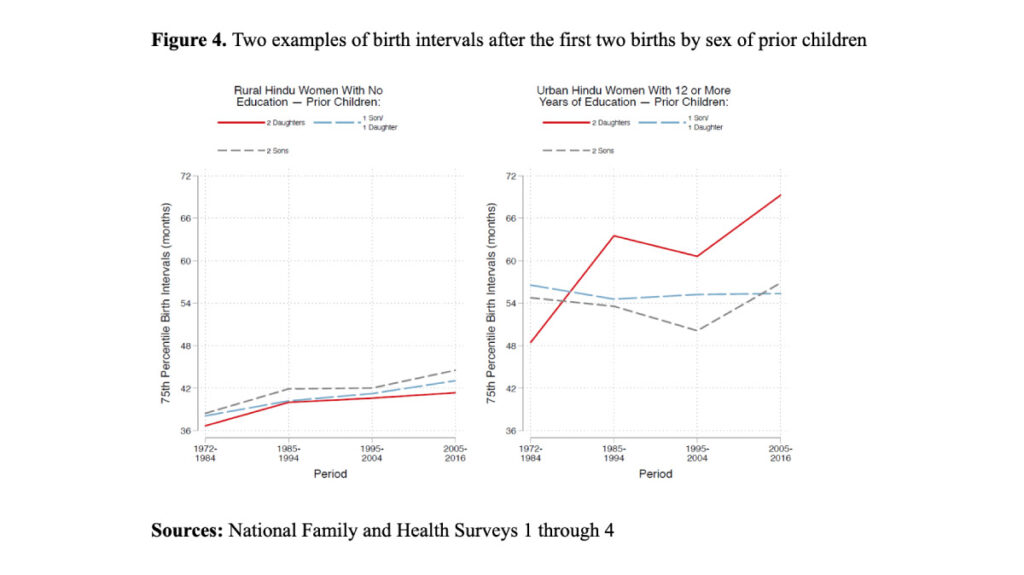

To illustrate some of the results, Figures 2 to 4 show the probability of a third birth, the percentage of boys among third births, and the 75th percentile birth intervals after the second child for rural women with no education and urban women with 12 or more years of education. These two groups represent the extremes in India and exemplify the divergent behaviors in response to son preference. Currently, the two groups constitute approximately 15% and 20% of the female Hindu population, respectively. The graphs for the other groups are available in Pörtner (2022). The analyses cover four periods: 1972–1984, 1985–1994, 1995–2004, and 2005–2016.

Fertility is falling, but son preference still affects the likelihood of a subsequent birth

First, consistent with declining overall fertility, the likelihood of a subsequent birth has decreased over time for all parities. However, the probability of having another child remained higher for women without sons than for women with one or more sons, showing that son preference remains strong in India.

Consistent with these general trends, both groups of women shown in Figure 2 are less likely to have a third child, but are more likely to do so if they already have two daughters than if they have one or two sons. However, more than 75% of rural women with no education still have a third birth whatever the sex of their prior children. This contrasts with highly educated urban women, among whom less than 20% have a third child if they already have a boy, while more than 50% have a third child if they have only daughters.

The use of sex selection is not declining

Second, despite predictions that sex selection will eventually decline in India, there is no clear evidence to support this idea. The most likely users of sex selection—more highly educated women with no sons—continue to show substantial male-biased births. More worryingly, increasingly male-biased births among less-educated mothers suggest that sex selection is spreading as the fertility of this group declines.

The highly educated urban women in Figure 3 illustrate how the percentage of boys at birth increased for mothers with no sons as access to sex selection spread. For this group, we are fast approaching a situation where 80% of third births are boys, reflecting the fact that, as desired fertility declines, more and more women use sex selection to secure a boy before they stop childbearing.

The situation is very different for rural women with no education. Their fertility is still high, and the chance of having a son without sex selection is correspondingly high. Hence, there is still no evidence of sex selection for this group, although this might change in the future as fertility declines further.

Modest increases in birth intervals, except with sex selection

Based on the percentage of boys at birth, we can split Hindu births into two broad groups. The first group, without evidence of sex selection, includes births to highly educated mothers with at least one son and all less-educated mothers whether or not they have a son. The second, with evidence of sex selection, includes births to more highly educated mothers with no sons.

For births where sex selection is not used, median birth intervals have increased relatively little—by only three to six months over the four decades—compared to around 3.5 months per decade in other countries with declining fertility (Casterline & Odden, 2016). Despite the absence of sex selection, there is still strong evidence of son preference, as illustrated by the shorter birth intervals when rural women with no education have only daughters than when they have at least one son.

What is more, a remarkably high proportion of birth intervals are still very short. Except among the most educated women, 25% or more have their second child within 24 months of their first, and a similar proportion have their third child within 24 months of their second. These intervals are substantially below the WHO recommended 24 months between pregnancies, resulting in significantly higher child mortality risk, especially for less-educated mothers (Bocquier et al., 2021; Pörtner, 2022).

The story is very different when sex selection is used. Highly educated mothers with no sons have substantial lengthening of birth intervals, further evidence of very significant use of sex-selective abortion. For example, among highly educated urban mothers with only daughters, the 75th percentile birth interval length is now nearly 70 months, a 21-month increase over four decades. Strikingly, more than 70% of this increase occurred in the first decade after the introduction of sex selection. Therefore, some mothers with no sons now have longer birth intervals than those with sons, reversing India’s traditional spacing pattern.

Spread of sex selection led to overestimation of fertility decline

One of the unappreciated effects of the rapid expansion of sex selection and the associated increases in birth intervals is that it makes the TFR a downward-biased estimate of cohort fertility (Bongaarts, 1999; Hotz et al., 1997; Nı́ Bhrolcháin, 2011). That is precisely what appears to have happened in India. The period fertility rate substantially overestimated the speed of cohort fertility decline in the 1990s and early 2000s, as spacing increased with the spread of sex selection. For example, the TFR for urban women with 12 or more years of education went from 2.1 to around 1.6 with the introduction of ultrasound sex determination, but predicted cohort fertility declined only from 2.3 to 2.1. Although the two fertility measures have recently partly converged, predicted cohort fertility is still 10-20% higher than the period fertility rate.

These results paint a less rosy picture of India’s prospects for a continued reduction in population growth than generally accepted. With predicted cohort fertility still substantially higher than the period fertility rate, India’s TFR will likely stabilize or even increase as birth intervals lengthen more slowly. Perversely, the more successful our attempts at combatting sex selection, the greater the likelihood of an increase in the TFR. This increase stems partly from the shortening of birth intervals if sex-selective abortions are unavailable and partly from families needing more births to have at least one son.

References

Bocquier, P., Ginsburg, C., Menashe-Oren, A., Compaoré, Y., & Collinson, M. (2021). Closely spaced births reduce survival chances of existing and future children. N-IUSSP.

Bongaarts, J. (1999). The fertility impact of changes in the timing of childbearing in the developing world. Population Studies, 53(3), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720308088

Casterline, J. B., & Odden, C. (2016). Trends in inter-birth intervals in developing countries 1965–2014. Population and Development Review, 42(2), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00134.x

Hotz, V. J., Klerman, J. A., & Willis, R. J. (1997). The economics of fertility in developed countries. In M. R. Rosenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of population and family economics (pp. 275–347). Elsevier B.V.

Jayachandran, S. (2017). Fertility decline and missing women. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(1), 118–139. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20150576

Nı́ Bhrolcháin, M. (2011). Tempo and the TFR. Demography, 48(3), 841–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0033-4

Pörtner, C. C. (2022). Birth Spacing and Fertility in the Presence of Son Preference and Sex-Selective Abortions: India’s Experience Over Four Decades. Demography, 59(1), 61–88. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9580703 Pörtner, C. C. (2015). Sex-selective abortions, fertility, and birth spacing (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7189). World Bank.