Gender equality in child care can be promoted through individual entitlements to a non-transferable and well-paid leave of equal duration for women and men. While this design is still rare in Europe, Spain may have become a forerunner, say Teresa Jurado-Guerrero and Jacobo Muñoz-Comet.

Fathers’ involvement in childcare: society and policy

Many factors are causing European couples to adopt more gender-balanced work-life arrangements. Higher levels of tertiary education among women have increased female employment rates. Greater educational homogamy and hypogamy among younger couples (meaning that the woman’s level of education is equal to or higher than the man’s), higher divorce rates and low fertility levels enable more women to demand that men assume their fair share of housework and childcare. The number of dual-earner couples has increased as a consequence. Policies are following social demands to promote men’s involvement in childcare, especially at the turning point of entry into fatherhood (Moss and Duvander 2019).

A relevant policy example is the recent European Directive on Work-Life Balance (2019/1158), which aims to promote equal sharing of care and work responsibilities through greater involvement of men in domestic tasks. A couple of years earlier, the EU Commission had indicated that well-paid, individual and non-transferable leaves are a core instrument to promote involved fathering (European Commission 2017). However, the 2019 directive itself has been somewhat shy in stipulating the length of leaves for fathers and their wage replacement level, due to differing views and existing practices across EU member states. Indeed, the provision of 10 days of paternity leave paid at the same level as sick leave and two months of non-transferable parental leave to be paid at a level set by Member States has defined standards below the existing entitlements in several EU countries (Koslowski et al. 2021).

2019: Spain takes the lead?

In 2019, Spain approved a more ambitious reform. It established 16 weeks of individual, non-transferable leave on full pay for fathers and mothers, implemented on a progressive basis. Spain has therefore become the EU country with the longest leave for fathers, and the only one where a well-paid and non-transferable leave is of equal duration for both parents.

This new 2019 leave system has been established for different reasons, such as a strong feminist movement, a civic platform lobbying for it since 2005,1 a left-wing coalition government and a high proportion of fathers having used the previous (shorter) paternity leave. In a recent paper, we looked at trends in paternity leave take‑up rates from 2008, when a two-week paternity leave was introduced, to 2018, when it was extended to five weeks (Jurado-Guerrero, Muñoz-Comet 2020).

A success story: 2008-2018

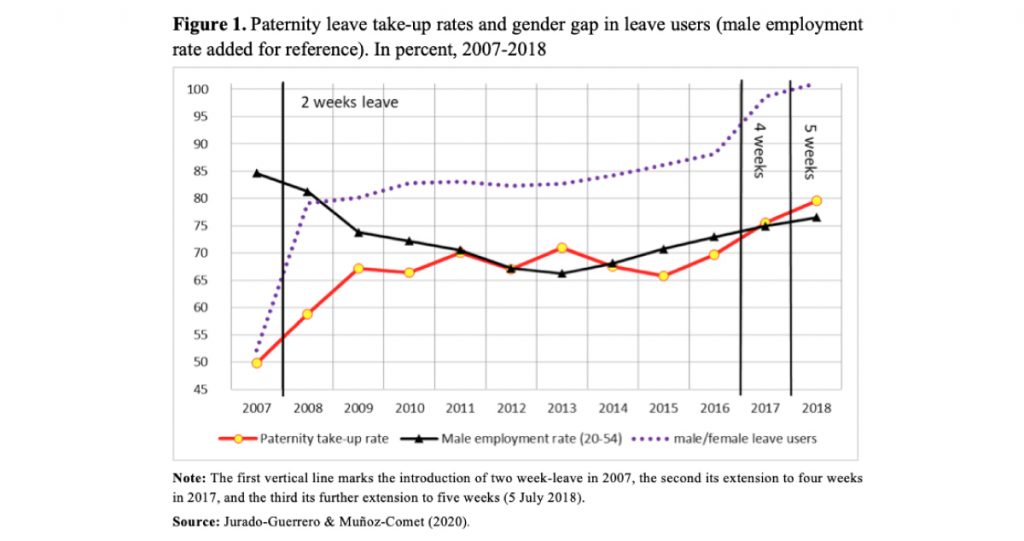

We calculated the paternity take-up rate as the proportion of fathers aged 20-49 among those in employment who took the leave. Figure 1 shows that the extension to four and five weeks increased take-up rates from the previous level of 70% up to 80% in 2018, with an average leave of 30 days.

Of the 20% or so of working fathers who did not use paternity leave, some may have feared being penalized at work or felt they could not be properly replaced during their absence. More importantly, there are regulatory reasons: not all working fathers are entitled to a paid leave due to the informal nature of their jobs or to insufficient previous social security contributions. Note that benefits are based on past social security contributions, which may not reflect self-employed fathers’ true monthly income (partly concealed from the fiscal authorities): in short, paternity allowances, in these cases, do not fully replace real incomes.

However, in a comparative perspective, an 80% take-up rate is a clear success story (Koslowski et al. 2020) and has narrowed the gender gap in leave allowances. More than that, actually: in 2018 slightly more fathers than mothers took their parental leave (although it is also fair to add that men more often have jobs with better social security coverage, and therefore have a stronger incentive to tap this resource).

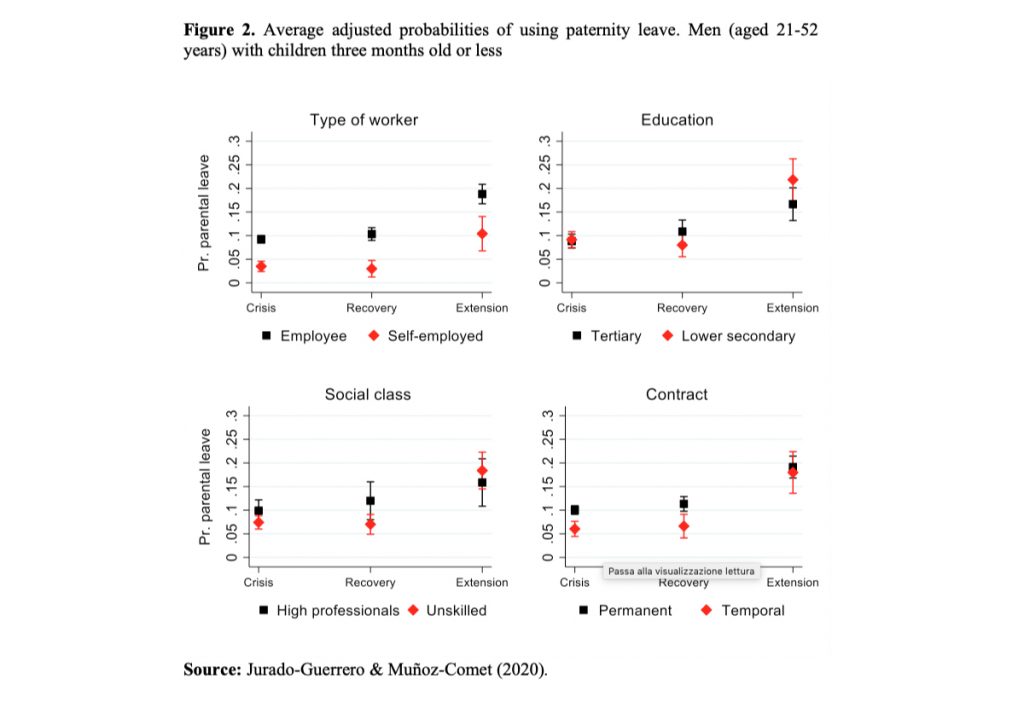

Taking paternity leave seems to have become a social norm that cuts across different social groups. We analysed how fathers’ likelihood of uptake evolved over the whole period across social groups, during the economic crisis (2008–2013); during the economic recovery (2014–2016); and during the parental leave extension to 4/5 weeks (2017–2018).

Figure 2 shows the average adjusted probabilities of using paternity leave for fathers by type of employment, educational level, social class and type of contract, the four most frequent social divides identified in research. Note, first, that changes over time are statistically significant only during the period of leave expansion.

During this final period, a reduction was observed in the take-up gap between employed and self-employed fathers (top left) and also between fathers with permanent and fixed-term contracts (bottom right). Even more than that, the gap between fathers with tertiary education and those with lower secondary education or less even reversed (top right), as did the gap between professionals and unskilled workers (bottom left).

This norm of extended paternity leave proved somewhat less effective for immigrant fathers, fathers with an inactive wife and those working in the private sector. Overall, however, the political and social legitimation of paternity leave now seems to be well established in Spain.

Good intentions and practical results

Little is known as yet about the 2021 reform that increases leave to 16 weeks. The first indications are good: fathers seem to have been particularly keen to use it (more male than female beneficiaries). However, in 75% of cases, fathers use the leave simultaneously with mothers, immediately after the birth. Nice as it may be for parents to share the joys of a newborn child, the practical issue of taking turns to look after the baby may not have found a better solution with the new law. Indeed, according to the international platform PLENT, the new law has a pitfall: fathers are obliged to use their leave together with the mother, while most couples would probably prefer to take leave alternately in order to facilitate the mother’s return to the labour market. On top of that, we do not yet know how many weeks fathers have taken up, or if they use the leave full- or part-time. And we may not know until a survey is conducted, because the Spanish social security releases little current information, and does not provide the data required to monitor and evaluate the effects of the reform.

In short, while the new Spanish leave system is better designed in principle for equal use than the 2019 EU directive, it may have made equal sharing of childcare more difficult than it was before.

References

European Commission (2017) Communication from the Commission to the European parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – An initiative to support work-life balance for working parents and carers, Brussels, 26.4.2017, COM(2017) 252 final.

Jurado-Guerrero T., Muñoz-Comet J. (2021) Design Matters Most: Changing Social Gaps in the Use of Fathers’ Leave in Spain. Population Research and Policy Review, 40: 589-615. Koslowski, A., Blum, S., Dobrotić, I., Kaufman, G. and Moss, P. (2021) International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2021. DOI: 10.18445/20210817-144100-0. Available at: www.leavenetwork.org/annual-review-reports/review-2021/Moss P., Duvander A.Z. (Eds.) (2019) Parental leave and beyond: Recent international developments, current issues and future direc

[1] The Spanish platform for Equal and Non-transferable Birth and Adoption Leave