Freanch version below

Two years ago, Neodemos received an article from Valeria SOLESIN, a young student who was then unknown to most demographers, in Italy or elsewhere. She was later to make herself known, both in Italy and in France, where she had in the meantime become a PhD student. Her life ended tragically this 13 November, in the barbaric slaughter at the Bataclan concert hall in Paris.

The exhortation of the title “Allez les filles: au travail!” (in French in the original) resounds even more strongly today than it did two years ago: by translating and publishing her article on N-IUSSP, we wish to express our bitter sadness, to remember her commitment and honor her memory.

Female labour force participation in Europe has been promoted since the 1990s via the European Employment Strategy (EES). The European Union aims to encourage women to remain in employment throughout the life cycle, especially during periods when they are considered to be at risk, such as in early motherhood. While the number of women in the labour force has increased greatly in the European Union, there are still major disparities between countries. All the countries of northern Europe have high female employment rates combined with consistently high fertility. By contrast, the countries of southern Europe are characterized by low female employment rates and low fertility (OECD, 2011).

This contrast is also visible between France and Italy. In 2011 the labour force participation rate of women aged 20-64 was 65% in France, versus 50% in Italy, while the total fertility rate stood at 2 children per woman in France, and barely 1.4 in Italy. (ISTAT, 2012).

Yet these two countries have quite similar demographic profiles, with a population of around 60 million (not counting the French overseas territories) and a comparable life expectancy at birth. They also share a number of cultural traits, such as the Catholic religion, and geographical features, with 515 km of shared borders. Last, the two countries’ labour markets also have certain similarities. Both are quite rigid, although in Italy it is workers in the “traditional” sectors of economic activity (such as industry) who enjoy the greatest protection.

In the light of this information, how can we explain the large disparities in terms of fertility and female employment between these two European neighbours? Perhaps the traditional gender division of roles persists more strongly in Italy than in France.

Who should work? Opinions in France and Italy

Data from the 2008 European Values Study reveal sharply contrasting opinions on women’s labour force participation in France and Italy. In response to the affirmation that “A pre-school child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works”, 76% of Italian women “strongly agree” or “agree”, versus just 41% of French women. Moreover, in response to the statement “A working mother can establish just as warm and secure a relationship with her children as a mother who does not work” Italians reveal a more traditional attitude than their trans-Alpine neighbours. Just 19% “strongly agree”, compared with 61% among French men and women.

So Italians still tend to consider that women with preschool children should not go out to work. In France, on the other hand, women are encouraged to work at all stages of the life cycle, even when they have small children. This suggests that in Italy, women’s labour force participation may depend more strongly than in France on the ages of their children and their number.

Data from the 2008 European Values Study reveal sharply contrasting opinions on women’s labour force participation in France and Italy. In response to the affirmation that “A pre-school child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works”, 76% of Italian women “strongly agree” or “agree”, versus just 41% of French women. Moreover, in response to the statement “A working mother can establish just as warm and secure a relationship with her children as a mother who does not work” Italians reveal a more traditional attitude than their trans-Alpine neighbours. Just 19% “strongly agree”, compared with 61% among French men and women.

So Italians still tend to consider that women with preschool children should not go out to work. In France, on the other hand, women are encouraged to work at all stages of the life cycle, even when they have small children. This suggests that in Italy, women’s labour force participation may depend more strongly than in France on the ages of their children and their number.

Who are the working women in France and in Italy?

While Italians tend to think that young mothers should not work, the employment rate of women with preschool children (55%) is quite similar to that of women with no children below age six (61%). In France, by contrast, while women’s employment is largely supported throughout the life cycle, their employment rate falls sharply when they have young children (66% for women with one or more children below age 6, versus 80% for those with no preschool children). This is linked to that fact that France has implemented measures to reconcile work and family life which enable women (and men) to take parental leave to look after small children.

In conclusion

At a time when women’s employment is being encouraged in Europe, it is important to take account of the impact of childbearing on their labour force participation. Italy is aiming to reach the target of 60% female labour force participation laid down by the Treaty of Lisbon. In France, a country with a better record in this area, women’s employment still depends on the number of children in the household and their age. For this reason, a more equal gender division of paid employment and of household tasks should be encouraged in both countries.

Bibliographic references

ISTAT, 2012, Noi Italia, 100 statistiche per capire il paese in cui viviamo, www.istat.it

OECD, 2011, Doing better for families. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Freanch version

Voici 2 ans, Neodemos a reçu l’article d’une jeune étudiante, Valeria SOLESIN, inconnue de la plupart des démographes en Italie comme ailleurs. Elle s’est fait connaître par la suite en Italie et en France, où elle était doctorante. Sa vie a brutalement pris fin le 13 novembre dans le massacre du Bataclan à Paris. L’exhortation contenue dans le titre de son article « Allez les filles : au travail! » sonne plus fort encore aujourd’hui qu’il y a 2 ans. Nous traduisons et publions son article sur N-IUSSP avec une profonde tristesse, pour nous souvenir de son engagement et honorer sa mémoire.

En Europe, l’activité féminine est promue depuis les années 1990 à travers la Stratégie européenne pour l’emploi (SEE). L’objectif de la Communauté européenne est de favoriser l’emploi féminin tout au long du cycle de vie, et en particulier dans les périodes considérées à risque, au moment de l’arrivée des enfants. Bien que la participation des femmes au marché du travail ait fortement augmenté dans l’Union européenne, d’importantes différences persistent entre pays. Tous les pays du nord de l’Europe se caractérisent par de forts taux d’activité féminine et une fécondité qui reste élevée. Au contraire, dans tous les pays d’Europe du sud, de faibles taux d’activité féminine vont de pair avec des bas niveaux de fécondité (OCDE, 2011).

Ce contraste est également visible entre la France et l’Italie. En 2011, le taux d’activité des femmes de 20 à 64 ans était de 65 % en France contre 50 % en Italie, alors que l’indicateur conjoncturel de fécondité était de 2 enfants par femme en France, mais atteignait à peine 1,4 en Italie. (ISTAT, 2012).

Pourtant ces deux pays ont des caractéristiques démographiques assez similaires, avec une population d’environ 60 millions d’habitants (si l’on se limite à la France métropolitaine) et une espérance de vie à la naissance comparable. Ils partagent aussi des particularités culturelles, comme la religion catholique, et géographiques avec 515 km de frontières communes. Enfin l’organisation du marché du travail semble répondre à une logique assez semblable : relativement rigide, avec néanmoins en Italie une protection essentiellement dirigée vers les travailleurs appartenant à des branches d’activité « typiques » (comme l’industrie).

À la lumière de ces informations, il semble logique de se demander comment ces deux pays voisins peuvent être aussi différents en termes de fécondité et de participation féminine au marché du travail. Une explication possible serait qu’en Italie, plus qu’en France, il persiste une vision traditionnelle des rôles assignés aux hommes et aux femmes.

Le travail, pour qui? Les opinions des Italiens et des Français

Les données de la European Values Study de 2008 montrent de forts contrastes entre les opinions des Français et des Italiens sur la participation des femmes au marché du travail.

Face à l’affirmation « Un enfant qui n’a pas encore l’âge d’aller à l’école a des chances de souffrir si sa mère travaille », 76 % des Italiens et des Italiennes répondent « tout à fait d’accord » ou « plutôt d’accord », alors que c’est seulement le cas de 41 % des Français et des Françaises. De plus, face à l’affirmation « Une mère qui travaille peut avoir avec ses enfants des relations aussi chaleureuses et sécurisantes qu’une mère qui ne travaille pas », les Italiens font preuve d’une attitude plus traditionnelle que leurs voisins transalpins. Seulement 19 % se disent « tout à fait d’accord » alors que ce pourcentage atteint 61% chez les Français et Françaises.

En Italie, il persiste donc une vision négative du travail des femmes qui ont des enfants d’âge préscolaire. En France, au contraire, le travail féminin est encouragé à tous les stades du cycle de vie, même si les enfants sont encore petits. On peut donc penser qu’en Italie plus qu’en France, la participation des femmes au marché du travail peut dépendre de l’âge et du nombre d’enfants..

Qui sont les femmes qui travaillent en France et en Italie ?

Selon les données des enquêtes sur la population active (Labour Force Survey) de 2011 dans les deux pays, le taux d’activité des femmes sans enfants est toujours supérieur à celui des femmes avec enfants. En Italie, la situation est très contrastée puisque, à 15-49 ans, 76% des femmes sans enfants travaillent contre seulement 55% des femmes avec enfants. En France les taux sont de 81% dans le premier cas et de 74 % dans le second.

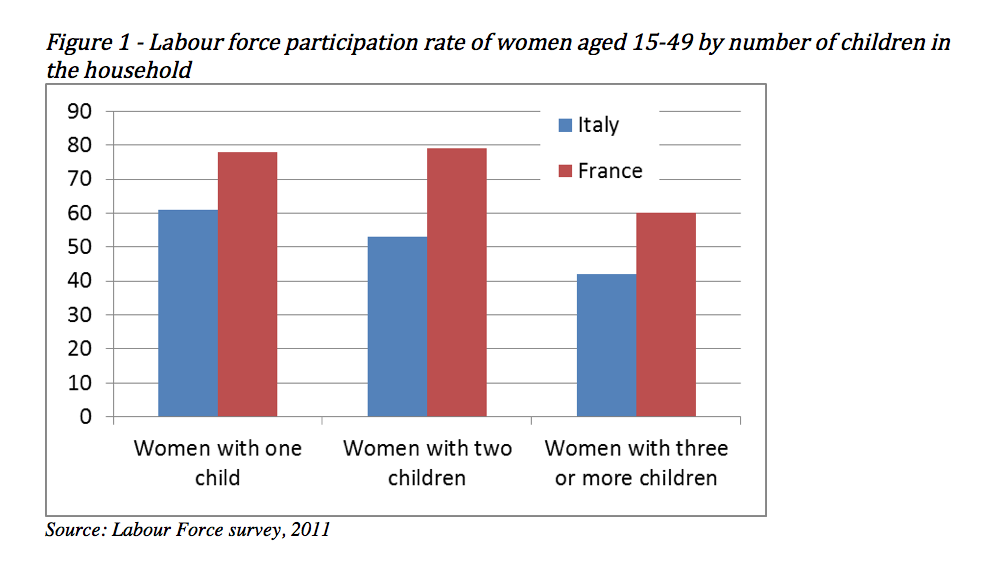

Par ailleurs, en Italie, le taux d’activité des femmes dépend de la taille de la famille : il diminue au fur et à mesure que le nombre d’enfants augmente. En France, au contraire, le taux d’activité varie très peu en présence d’un ou deux enfants au foyer. Mais dans les deux pays, vivre dans un foyer comprenant trois enfants ou plus compromet sérieusement l’activité de la mère. En Italie, à 25-49 ans, seulement 42% des femmes avec trois enfants sont professionnellement actives, alors que ce pourcentage s’élève à 60% en France.

Bien que les Italiens aient une opinion négative sur le travail des femmes qui ont de jeunes enfants, le taux d’activité des femmes avec enfants d’âge préscolaire (55%) est proche de celui des femmes n’ayant pas d’enfants de moins de 6 ans (61%). En France, à l’inverse, malgré une opinion positive sur le travail féminin pendant tout le cycle de vie, le taux d’activité est beaucoup plus bas en présence de jeunes enfants (66% pour les femmes avec un ou des enfants de moins de 6 ans contre 80 % pour celles n’en ayant pas). Dans ce pays, en fait, il existe des mesures de conciliation vie professionnelle-vie familiale qui permettent aux femmes (et aux hommes) d’interrompre momentanément leur activité professionnelle.

Pour conclure

Dans un contexte européen qui cherche à promouvoir l’emploi des femmes, il n’est pas possible d’ignorer les conséquences de l’arrivée des enfants sur l’activité féminine. L’Italie essaie d’atteindre l’objectif, fixé par le traité de Lisbonne, d’une activité féminine de 60%. En France, pays plus performant dans ce domaine, l’activité féminine dépend encore de l’âge et du nombre d’enfants présents dans le foyer. Pour cette raison, il paraît souhaitable d’assurer dans les deux pays un meilleur partage des tâches familiales et professionnelles entre hommes et femmes.

Références bibliographiques

ISTAT, 2012, Noi Italia, 100 statistiche per capire il paese in cui viviamo, www.istat.it

OECD, 2011, Doing better for families. Paris: OECD Publishing.